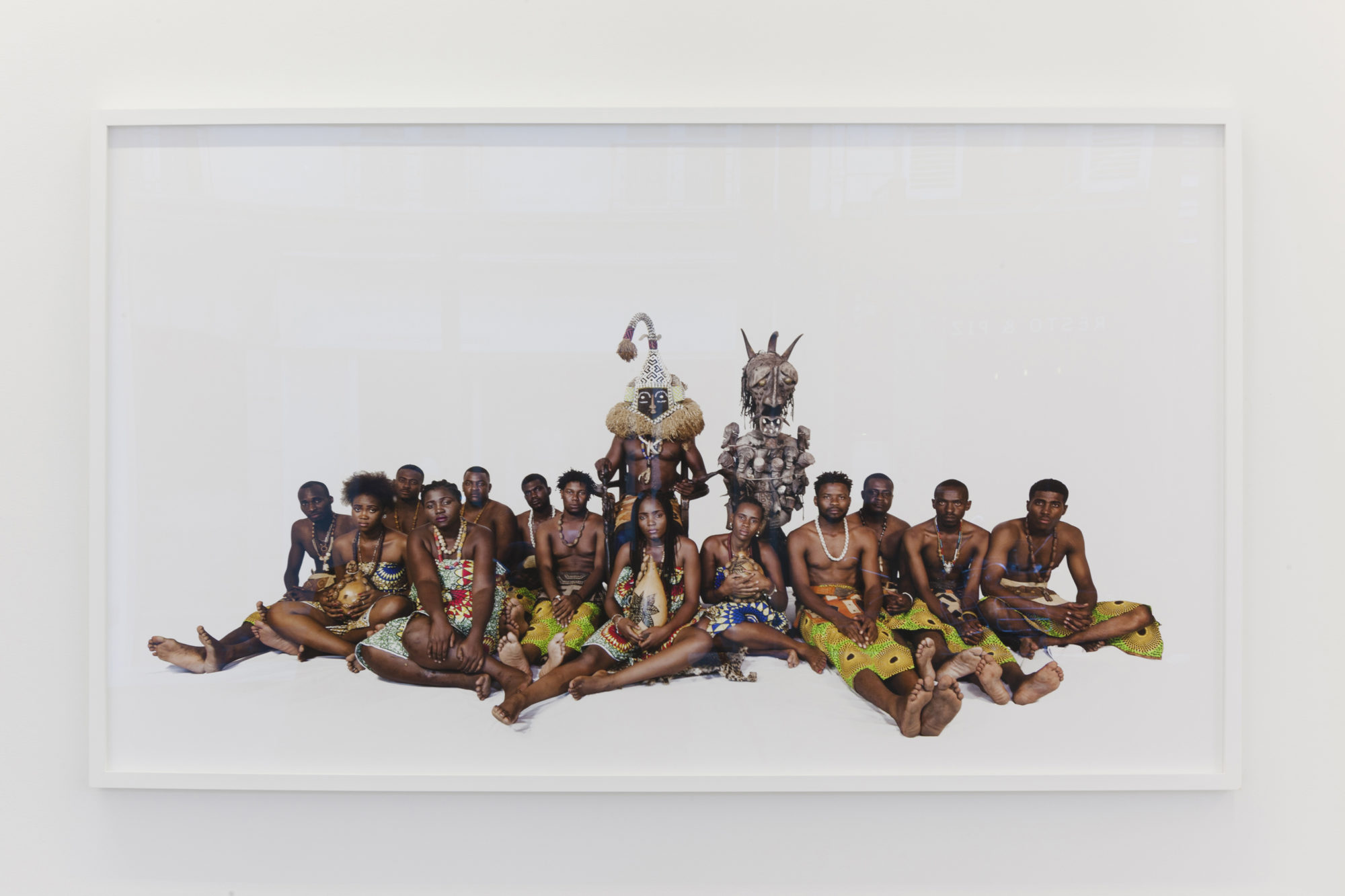

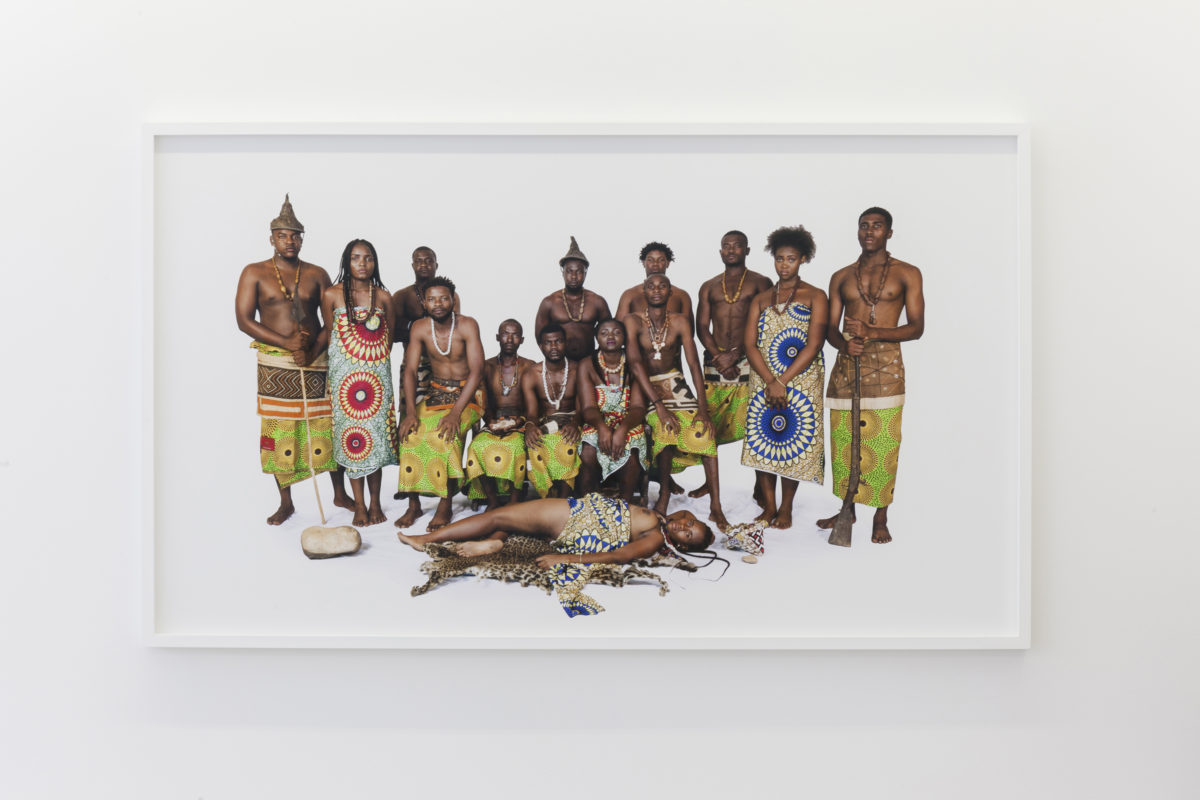

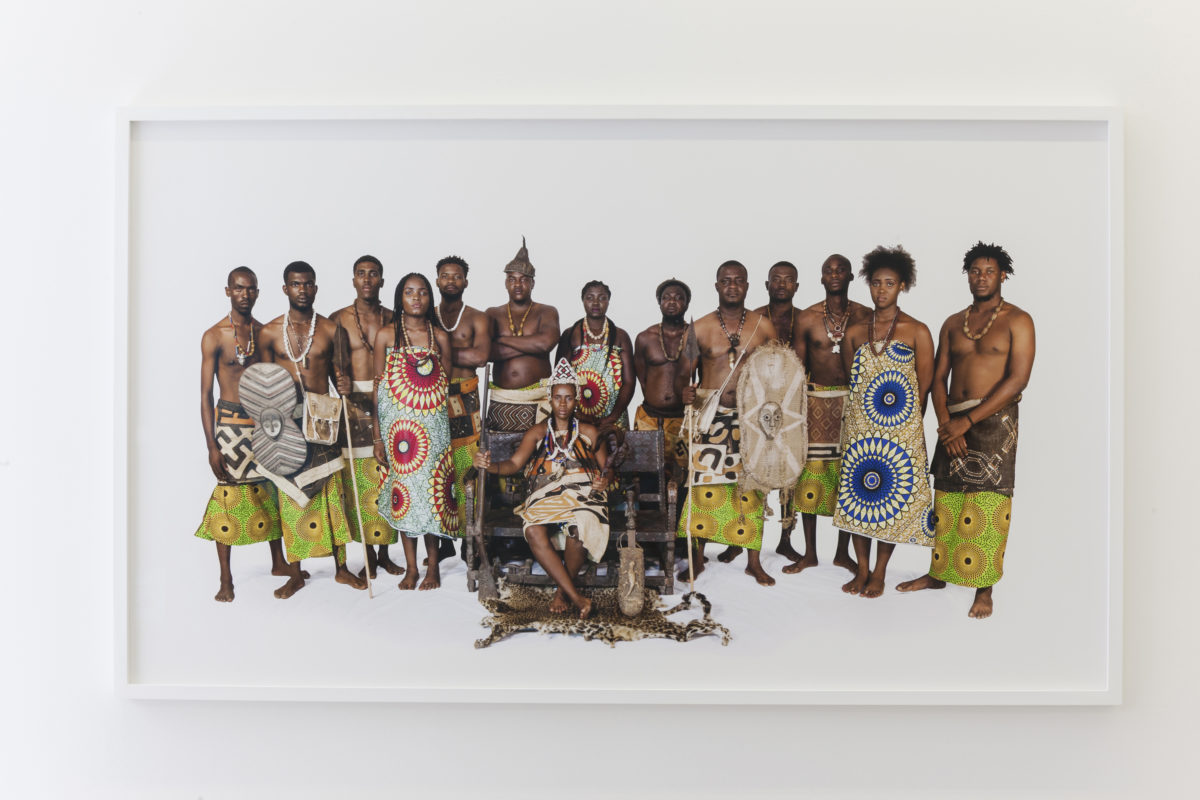

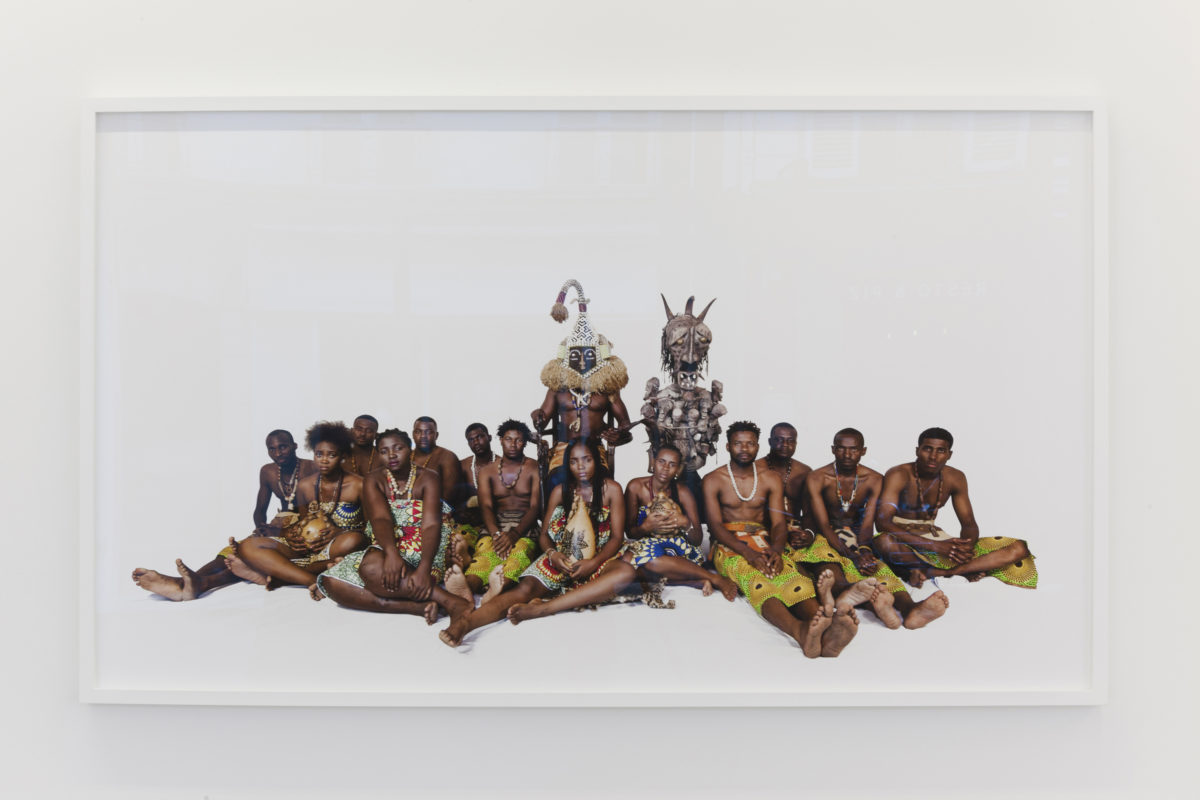

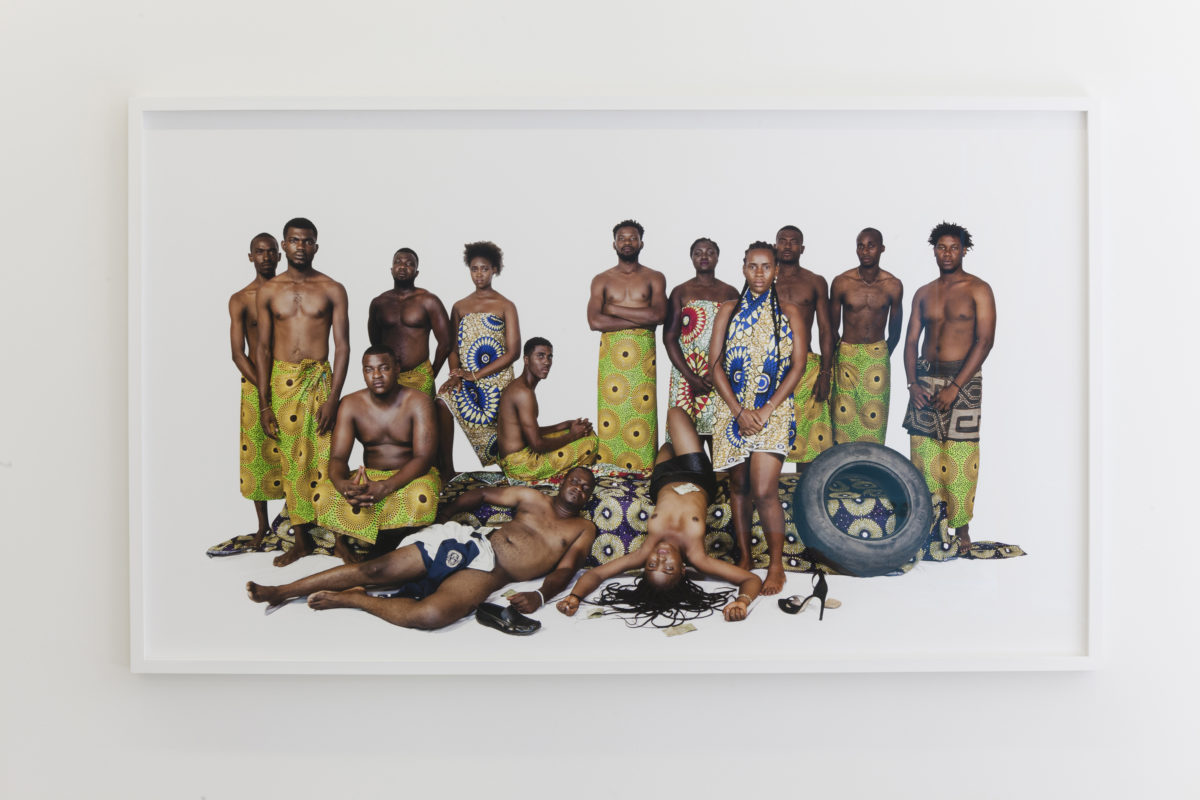

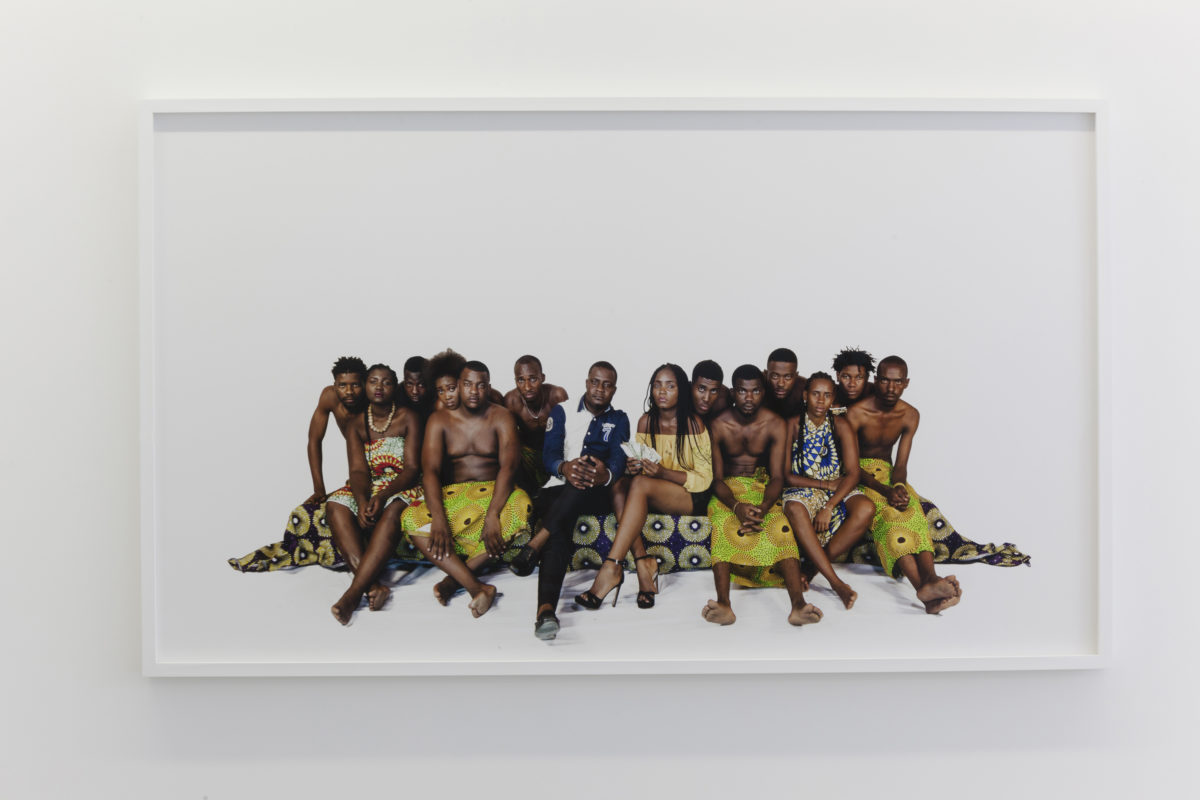

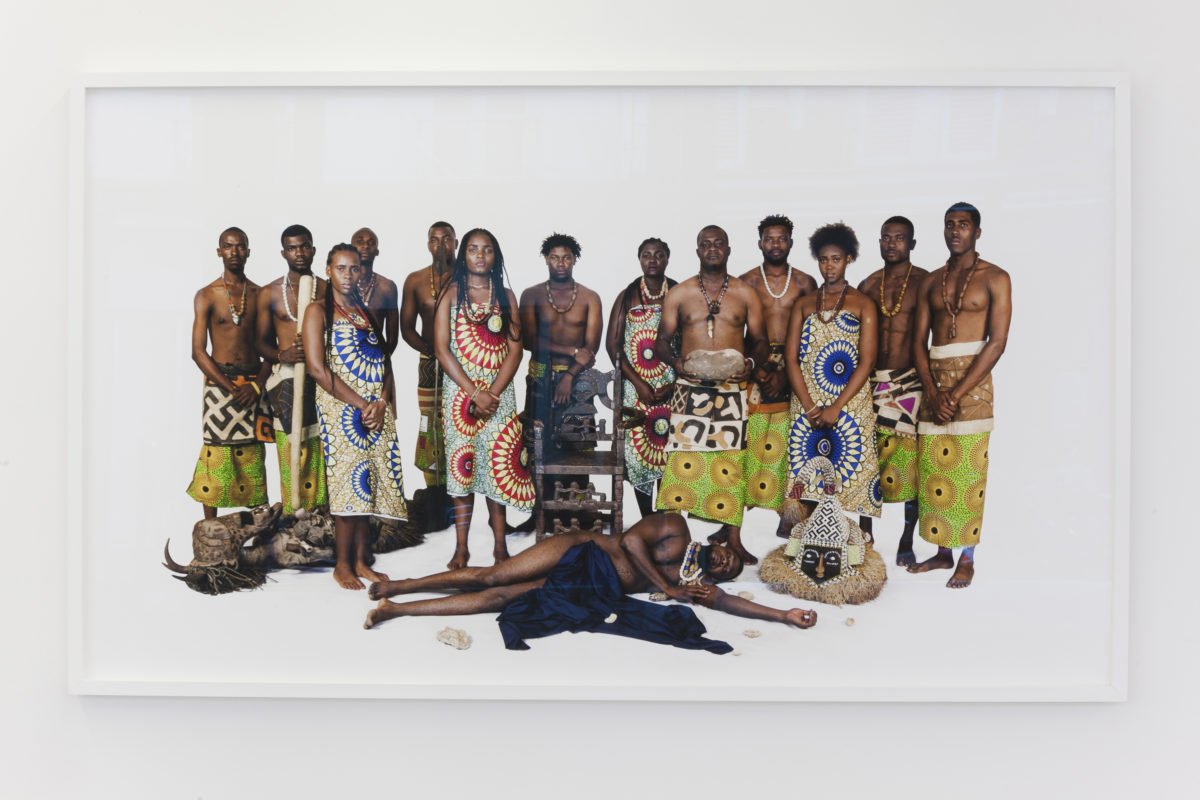

Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]Vue d’exposition

[+]Vue d’exposition

[-]

Vue d’exposition

Vue d’exposition

Vue d’exposition

Vue d’exposition

Vue d’exposition

Vue d’exposition

Vue d’exposition

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza