Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]Photo © Origins Studio

[+]Photo © Origins Studio

[-]

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

Photo © Origins Studio

The Improbable Memorial: shaping a possible reparation

In Goma, in the North-Kivu region where Sinzo Aanza grew up, the life of his family and of all the other inhabitants was devastated by the eruption of the Nyiragongo volcano in 2002, which buried his childhood house. Having witnessed in his childhood the extreme fragility of existence in the face of disasters, whether natural or man-made, Sinzo Aanzo is aware of the role played by the colonial power in this violent history and by the contemporary forms of the inhuman exploitation of natural resources. Educated in a Catholic school, he was asked one day to write a eulogy for a priest he had known.

In an interview with Céline Gahungu, he said that this was the moment he decided to enter literature: “I was writing eulogies for people whose death was linked to the insecurity we all experienced because of the war. War was violent and in each eulogy I was asked to write, I would write about all the other people who had died, those I saw dying, those I had seen dead, those I was told were dead, and ourselves, with our death always so close, so present, so obvious… This led me to abandon simple narratives and embrace poetry. This is what I called the Ngwaki1.”

As can be observed in the film-portrait of Kinshasa’s Kintambo cemetery by Filip de Boeck and Sarah Vanagt (Cemetery State, 2009), the funeral of any citizen becomes a moral critique of the old generation by the young. Psychologist Ferdinand Ezémbé describes in L’Enfant africain et ses univers (“The worlds of the African child”) (2009) how funeral rituals, which have a deep social and individual therapeutic function, become meaningless in a context of economic, political and social crisis: “The Congolese say that souls rest in a disorderly manner… or There is not enough tears to cry over all the dead2.”

The objects and ideas that compose the fragments of the Improbable memorial, of which a second chapter will be unveiled at the Kinshasa Yango Biennale in 2022, create a possible space for the existence of victims of the mineral exploitation systems and outline the beginning of a reparation of the precarious world of the living and the ignored world of the dead. This initiative comes from a personal, intimate quest that unfolds in the space left void by the lack of official recognition of the victims by the State.

However, as the title suggests, this memorial remains improbable given the current state of society, because the denial of History and memory covers and drowns everything. Sinzo Aanza observes such denial in the “victim” status, which he sees today as becoming blurry. Indeed, it is impossible not to perceive the Congolese people as the direct and indirect victims of the worldwide spread of mobile phones, which are made with many materials mined in Congo and whose ubiquitous and indispensable character extends the colonial exploitation of resources and people into the present time.

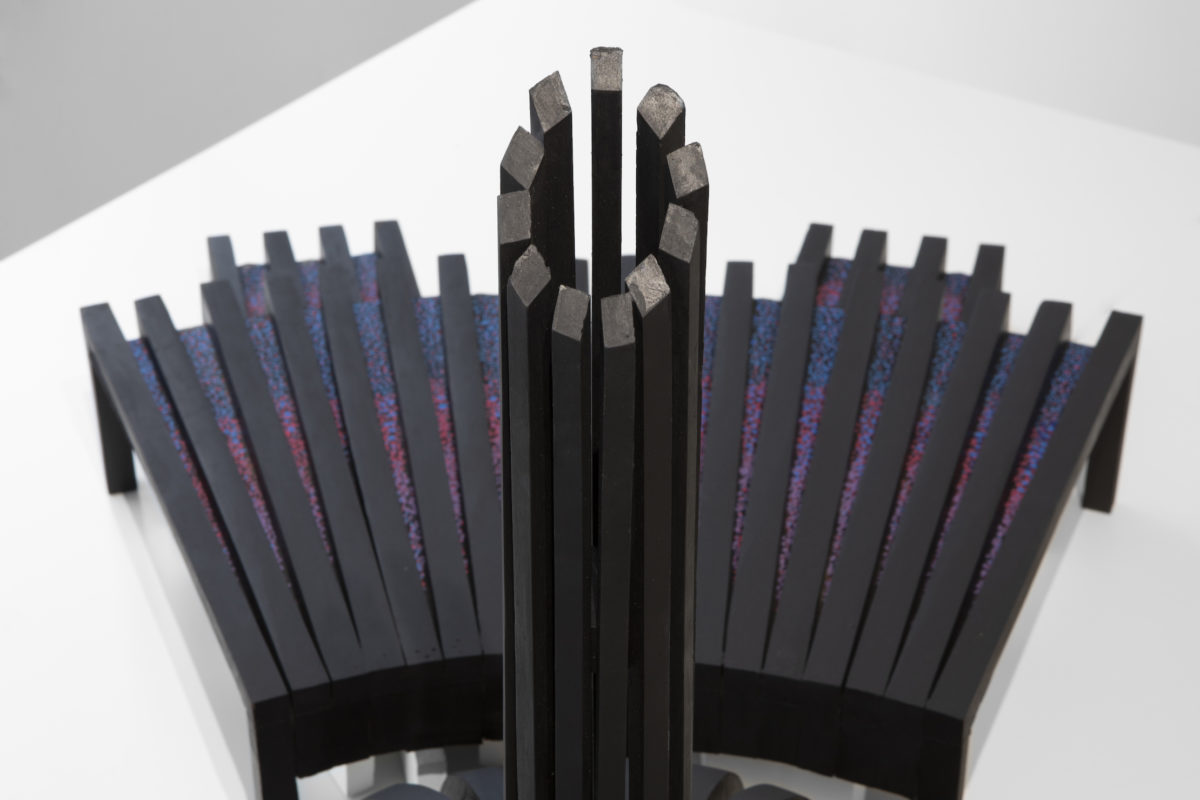

The exhibition opens with the memorial’s Maquette (Model). Large covered halls and smaller annex structures radiate around a big ribbed dome topped by a tower. The memorial is intended to be open and accessible to all, and its modular architecture allows for endless reproductions that could occupy the whole former ‘neutral’ zone of Kinshasa, between the ‘White Town’ and the ‘Black Town’ of the colonial era.

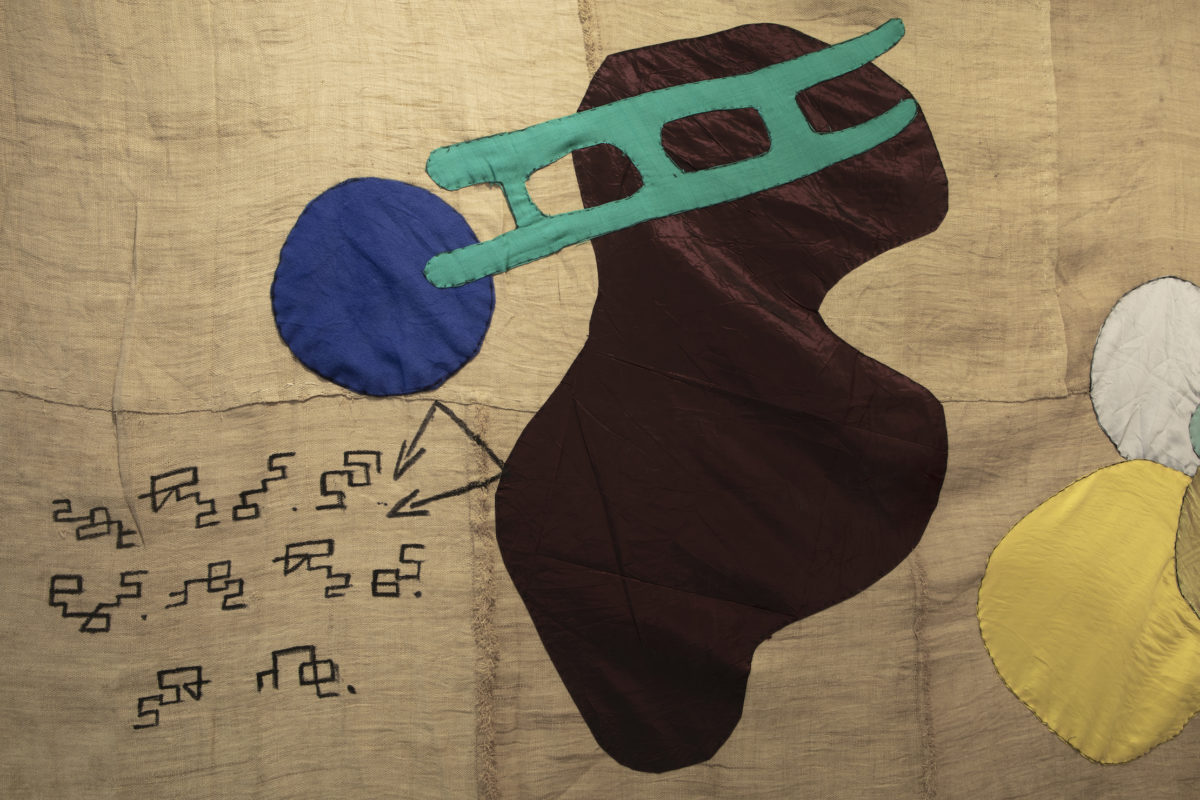

La Carte des choses possibles (“The map of possible things”) is a large tapestry in raffia and other fabrics representing an imaginary map of the Congo’s mines. It uses elements of the real map of the country’s mines, which are enriched with all the fantasies of the collective narratives about the localization of natural resources.

Texts written in Mandombe3 tell us (for those of us who can read them) about the nature of these resources, the meaning of shapes and colors, and the wisdom that is necessary to understand all that is buried.

La Toile (“The net”) is inspired by the ropes that adults tie around their children’s wrists to avoid losing them when large groups of population are displaced while fleeing armed conflicts. It also refers to the multiple ways in which loincloths are used to wrap, hold and hold onto precious or useful belongings during such migrations.

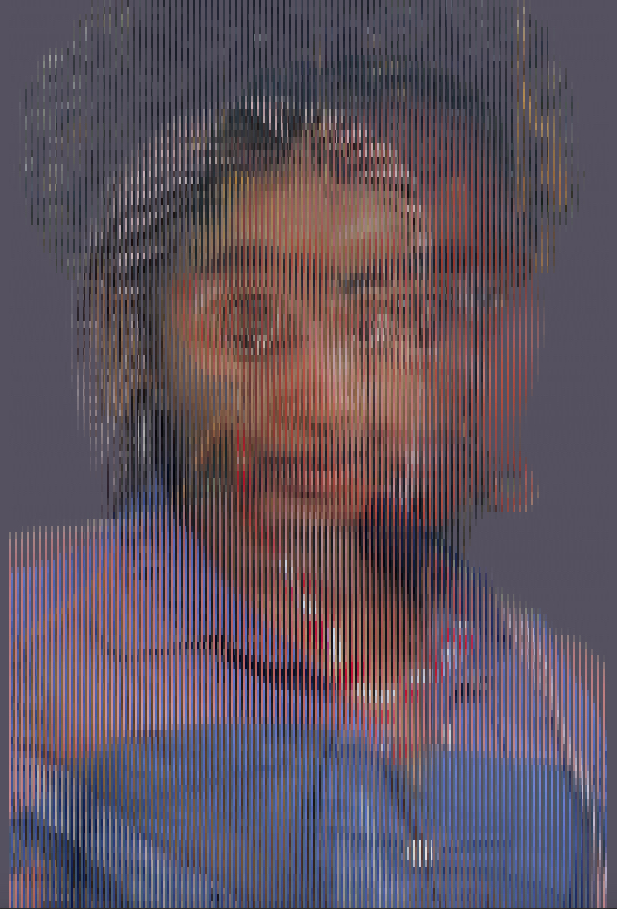

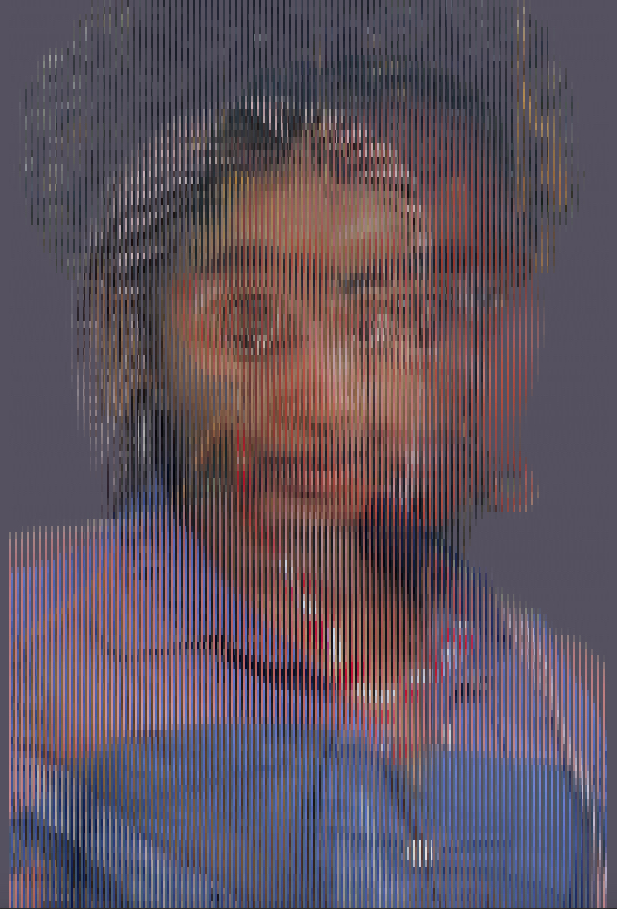

Le Portrait (“The portrait”) is a digital artwork that combines three different types of images: Fayum funerary portraits from Roman Egypt, made in the early centuries of our era; photographs handed by the families of the victims of massacres in the North-Kivu region, and selfies published on social media by anonymous people from all over the world. It is a confrontation between the gaze of these ‘ordinary’ people and the prospect of death for these men and women who do not leave behind any particular narrative or other type of achievement apart from the traces of their life or of their death.

The undulating motif represented by the six decorative panels embossed with rare minerals of La Fin du deuil (“The end of mourning”) is linked to the ritual of throwing hair in water at the end of the mourning period, which is still quite widespread in the Congo and other African countries. These panels are the basic decorative units that punctuate the walls inside the memorial. They symbolize all the people who died while mining the materials that shape them.

–Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez

1. Céline Gahungu, “Débords – Sinzo Aanza”, in Continents manuscrits. Génétique des textes littéraires – Afrique, Caraïbe, diaspora, nr. 10, 2018. Ngwaki is a type of poetry inspired by the traditional Nande dance, which is mainly performed by young people during funeral wakes. The dance defies death because of the liveliness of the living bodies, but also because they affirm that they belong to the same social body in which the dead are still living.

2. Ferdinand Ezémbé, “Dialogue avec les morts et les vivants”, in L’Enfant africain et ses univers, ed Karthala, 2009, pp. 247-254

3. Mandombe, which means ‘black African writing’ in Kikongo, is a graphic system that was invented or ‘discovered’ by David Wabeladio Payi (1957-2013), a Kongo from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, at the end of a long process that started in 1978.

Exhibition journal