Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Exhibition view. Photo © Tadzio

[+]Exhibition view. Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view. Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

For his second solo show at Galerie Imane Farès, James Webb presents a series of artworks resulting from extensive research and referring to the history of humanity, religions and thoughts. Choose the Universe is a call to welcome the unknown, to accept ambiguity, not to only consider obstacle as an impossibility, and to question the notion of mystery. It seems that the quest for the invisible, in the broad sense of the term, is at the heart of each of the artworks exhibited here. The history of psychoanalysis, but also various forms of spirituality (from Christianity to Animism and Buddhism) are all references used by the artist to represent what escapes our eyes and mind.

Placed in front of the wall, a Madonna with Child welcomes the visitor. Altered by time, the sculpture, entitled Invisibilia, seems to be coming back to life through a sonic transfusion. The recording of electromagnetic pulsations produced by the Aurora Borealis is broadcast through a transducer, which activates the plaster statue’s materiality and transforms it into a resonating chamber. The fact that the object has been turned towards the wall is a diversion reminiscent of a number of artworks that marked the history of modern art for their desacralising capacity. However, this gesture can also be seen as a ploy to pique the visitor’s curiosity. Both universal and intimate, the figure of this Madonna embodies love and protection but also resilience and humility in the face of infinite mystery.

Further on, James Webb uses, in a humorous way, a process often repeated in his practice, which is to juxtapose two or more elements in order to activate new possibilities. In the installation Friends of friends, he revisits the surrealist principle based on “the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table”1. A plastic houseplant and a silkscreen print by Joan Miró – both discarded by their respective owners – were bought in the same thrift shop by the artist and are brought together again in the space of the gallery. The objects are, at once, linked by fate and by chance. Their “encounter” can be compared to a blind date that just was meant to be: they share a path.

Indeed, the work also evokes what obstructs the view and blurs the mind. The Miró print mysteriously hides behind the plant, thus giving the installation a humoristic feel. Yet the origin of this artwork is actually more dramatic and lies in the story of a 17th century shipwreck. The survivors – a group of French Jesuit astronomers and Buddhist monks from Siam – got lost when trying to find an escape route in the nature surrounding Cape Town in South Africa. Associating natural landscape with imaginary landscape, the artist suggests that their ordeal could have ended better if they had been more open-minded. This story resonates well with his creative process, which is to “stay open in order to see and receive what is hidden behind the tangled thickets of [his] mind.”

The invisible and the ineffable meet in the series I do not live in this world alone, but in a thousand worlds. James Webb transcribes literary texts with ink on soluble paper, which he then dissolves in water and presents in glass flasks. These small bottles can be knocked down, or evaporate or even be drunk as a potion, a poison or a love philter. While poetry was central in the first pieces of this series started in 2016, here the artist explores the depths of the unconscious mind and the unknown. In I do not live in this world alone, but in a thousand worlds (Dreams of Franz Kafka), the selected texts refer to Franz Kafka’s dreams as he described them in his diary between 1910 and 1923. Excerpts from foundational texts (The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the haiku poems of the Zen Buddhist monk Ryokan, and Witness by Denise Levertov) are used for I do not live in this world alone, but in a thousand worlds (A Comet is Coming).

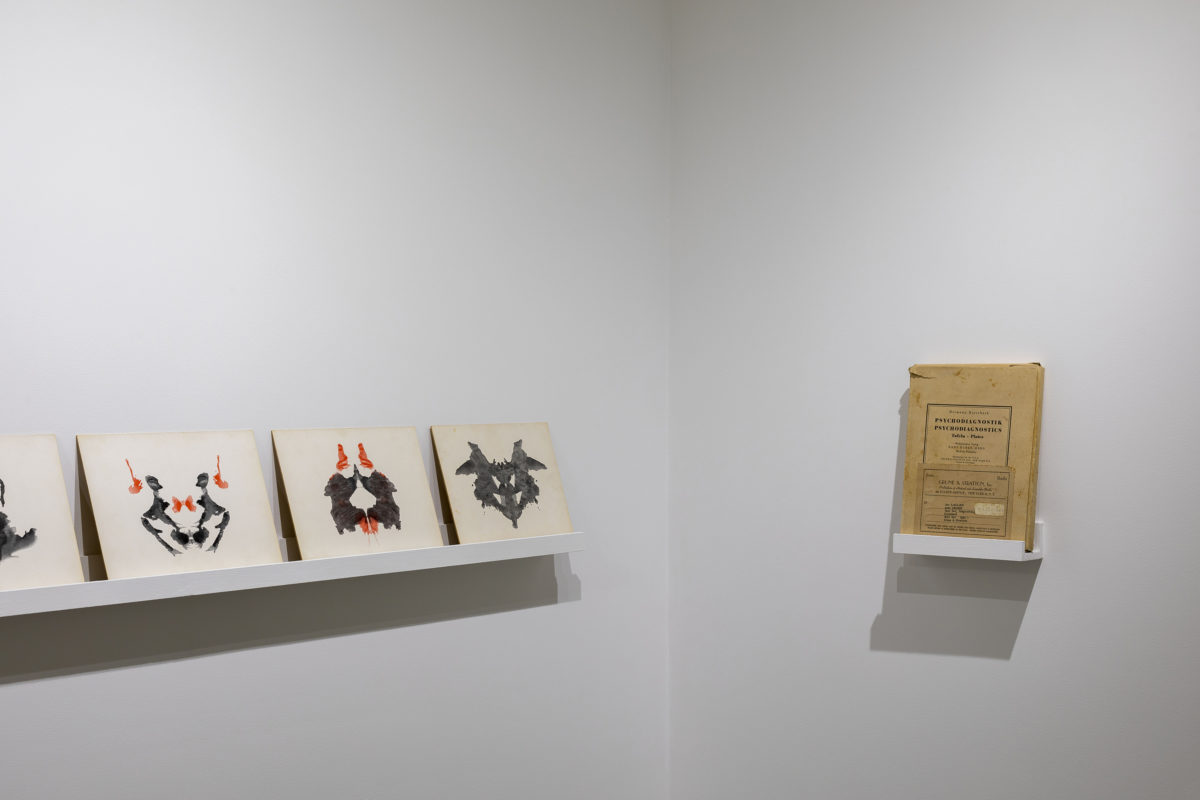

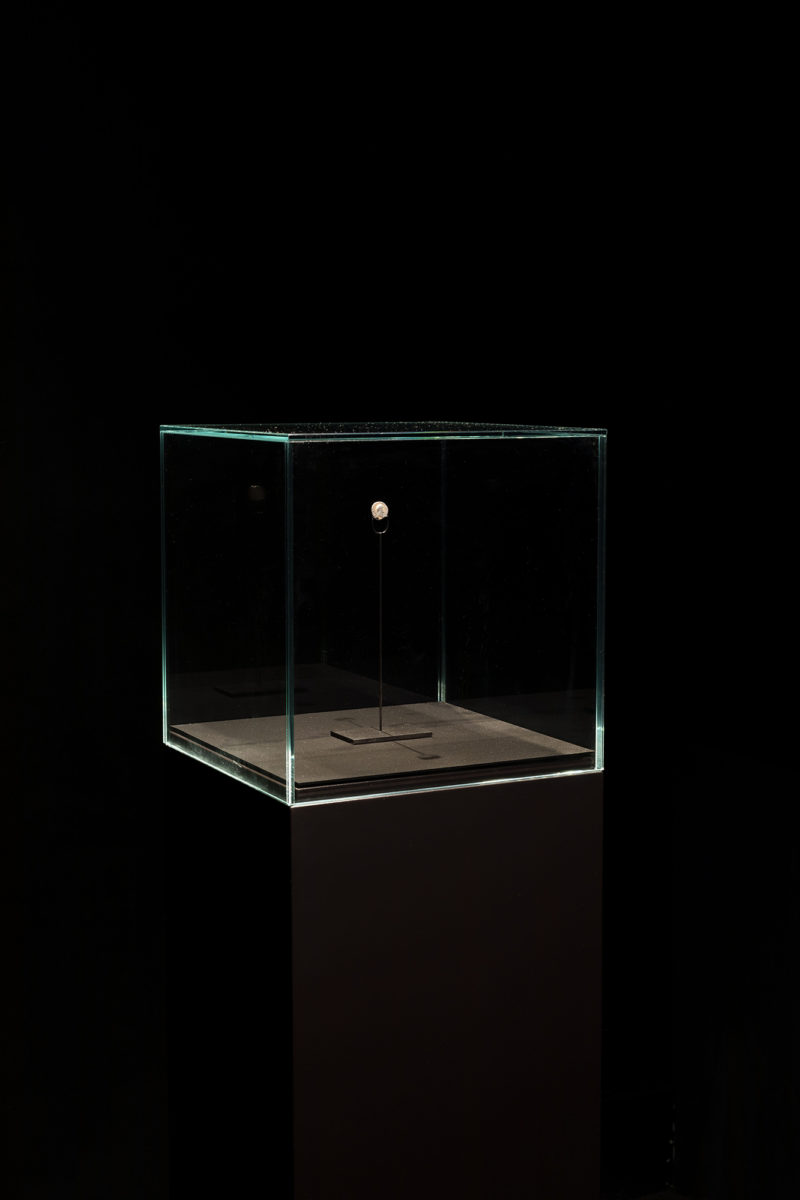

In parallel, also since 2016, the artist has chosen to ask questions to inanimate objects he carefully selects and considers as sentient beings capable of answering. After interviewing medieval church bells in the Swedish History Museum, an ambrotype from the Photography Museum of Tallinn, and a Chewa mask from Malawi, he presents two new artworks from this series. In A Series of personal questions addressed to a set of Rorschach Psychodiagnostic plates, a voice asks 65 questions to a set of cards conceived by Hermann Rorschach in 1921. The plates used for psychological evaluation can indeed produce a story that goes beyond their original purpose, which is to interpret ink stains. In the new artwork made especially for the show in Paris, A Series of personal questions addressed to a Roman Coin, James Webb rein-serts a coin showing the effigy of a Roman emperor into the mone-tary exchange circuit, thus interrogating its trajectory over the course of 1,900 years.

Lastly, the sound piece What Fresh Hell Is This broadcasts randomly throughout the gallery the sound of voices (laughs, songs, screams), the words “guilty” and “innocent” and the accusing sentence “You are procrastinating”, which comes from a dream the artist recently had. Staging the voice in an exhibition space is a recurring theme in James Webb’s oeuvre. Indeed, as one of Africa’s most prominent conceptual artists, using sound as one of his frequent materials, he believes that “voice activates space”.

— Odile Burluraux

1. The Songs of Maldoror, Comte de Lautréamont, 1869