Reactualisations

What is history? According to Walter Benjamin, the links between people are defined within the logic of dominating and being dominated, master and slave; and history is often established and written by the vanquisher. From the outset of his work, Sammy Baloji has decided to apply the paradox defined by Hegel in which the role of master and slave are reversed, which comes to another writing of History according to a contradictory point of view, in order to employ the term in its legal sense. The relationship between Africa and Europe, the secondary effects of the Berlin Conference, relations induced by this core data and the relationship to the other which is the foundation of ethnology, are placed under the spotlight by a work which, rather than denounce, subtly dismantles by using the outside perspective of the commentator.

This approach is somewhat reminiscent of Heterotopia, which according to Michel Foucault adapts different spaces in order to house utopias. But Baloji goes beyond physicality of spaces and extends the reflection on time and ideology; through his work he connects two other notions evoked by Foucault: heterochrony, a developmental change in the timing of events, leading to changes in size and shape, and heterology, “a discourse of the other, which is at once a speech on the other and a speech in which the other speaks.” Heterology is “an art of playing on two places”, which installs a reversible stage for which the last word does not necessarily belong to the first subject of the speech and where criticism does not spare the speaker who is reached indirectly. A place for experimentation, heterology assumes the risk of a speech in total freedom (Michel Foucault, The Order of Things) and is a wonderful instrument for attempting to assess in one place what is lacking in another, according to the words of François Julien.

Without question, this best applies to Baloji’s work than any other. Superimposing time and places, stories, archeology of places of remembrance (endogenous when it applies to people, exogenous when it applies to colonial memory), confrontations of points of view and the critical analysis of admissible ties; the heterology practiced by Sammy Baloji specifically questions through a juxtaposition without commentary, the disappearance of “what is missing”, by making it reappear by an osmotic phenomenon which gives rise to what we cannot see, or what we do not want to see. His home land of Kantanga still serves as a backdrop for his artistic work. The role of memory here lies neither within recollection, nor denunciation, but within an emergence and reactualisation of facts that belong just as much to our present as to our past, as exposed so well by Merleau-Ponty: “time remains the same because the past is a former future and a recent present, the present an upcoming past and a recent future, the future finally a present and even a past to come, that is to say because each dimension of time is treated or targeted as something other than itself, that is to say, finally, because there is at the heart of time, a look (…).” (Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception)

Sammy Baloji’s new exhibition at the Imane Farès Gallery is not an exhibition but a journey. A journey into time and space. A mise-en-abime of all the subjects that he has held dear over the last few years. Within this whole concept, we find the artist’s intellectual and artistic questions. How do we, through a work, translate the untranslatable? He has chosen to immerse us in his world in which, contrary to what the title suggests, an elephant would have a hard time dancing.

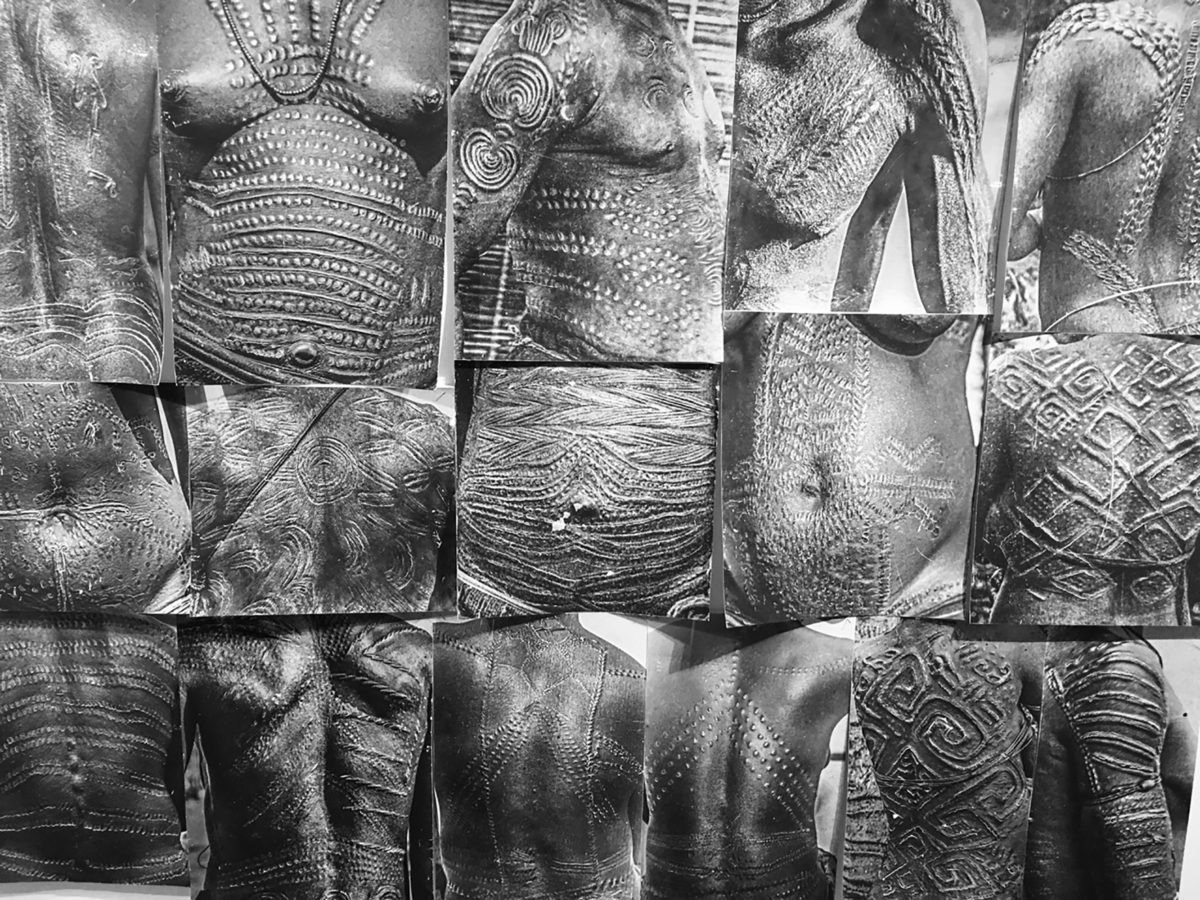

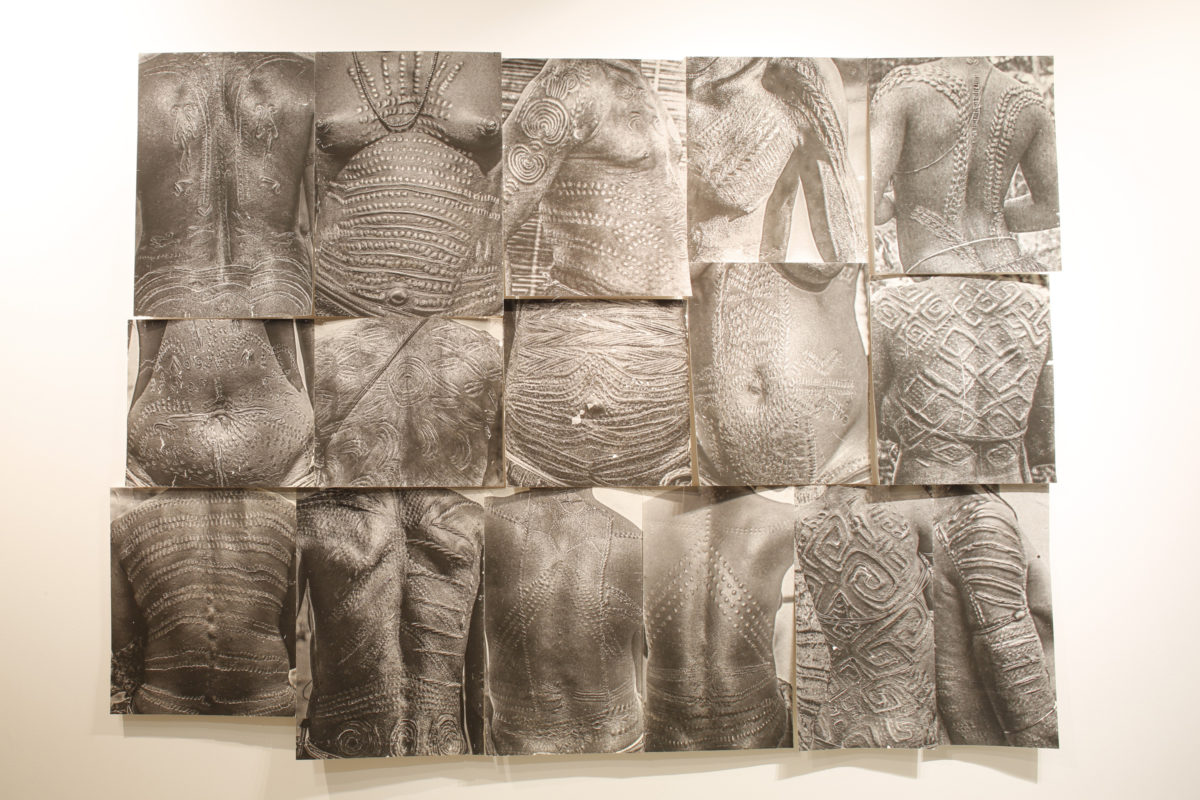

The room that we enter has an art deco touch that is reminiscent of early twentieth century colonial architecture. Much like a bull in a china shop, Baloji takes us to the heart of a brutal history that his gaze manages to sublimate, without losing tension. The wallpaper and ceiling trim derive their patterns from ritual scarifications, while shells transformed into flower pots are an ironic nod to a trend that the Belgian bourgeoisie maintained landing in the colonies.

On the walls a reminder (through an aerial photography archive) of mining and the conditions under which those who worked there lived. And then casually placed on the main table, like a book to read by the fire, The Vocabulary of Elizabethville by German anthropologist Johannes Fabian, in which the author collected the testimonies of African “domestic servants”, from Lubumbashi of course: we enter into the heart of the matter. It is the exploitation of man by man; it is these ‘unknown soldiers’, dead in the two European world wars that the artist wants to talk about.

And as we approach the second room, the reality of these scarified faces doesn’t only make reference to initiation rites, but metaphorical masks of injury, the scar and this memory that is reflected in the faces. These faces are punctuated by quotations borrowed from W.E.B. Du Bois, the legendary author of The Soul of Black Folks, and tell us of a mute anger, sadness or the duty of remembrance. Throughout this installation, we find the same author’s gaze which confuses time and history, in the sense that he assigns and unmasks them. We leave this strange journey into the troubled night, disturbed, but more aware of the mechanics of history and what colonisation was. Not, yet again, in a claimant and vindictive way, but as a constant, both discreet and moving. By the way, while I think about it: do you dance the Malinga?

— Simon Njami