Sinzo Aanza

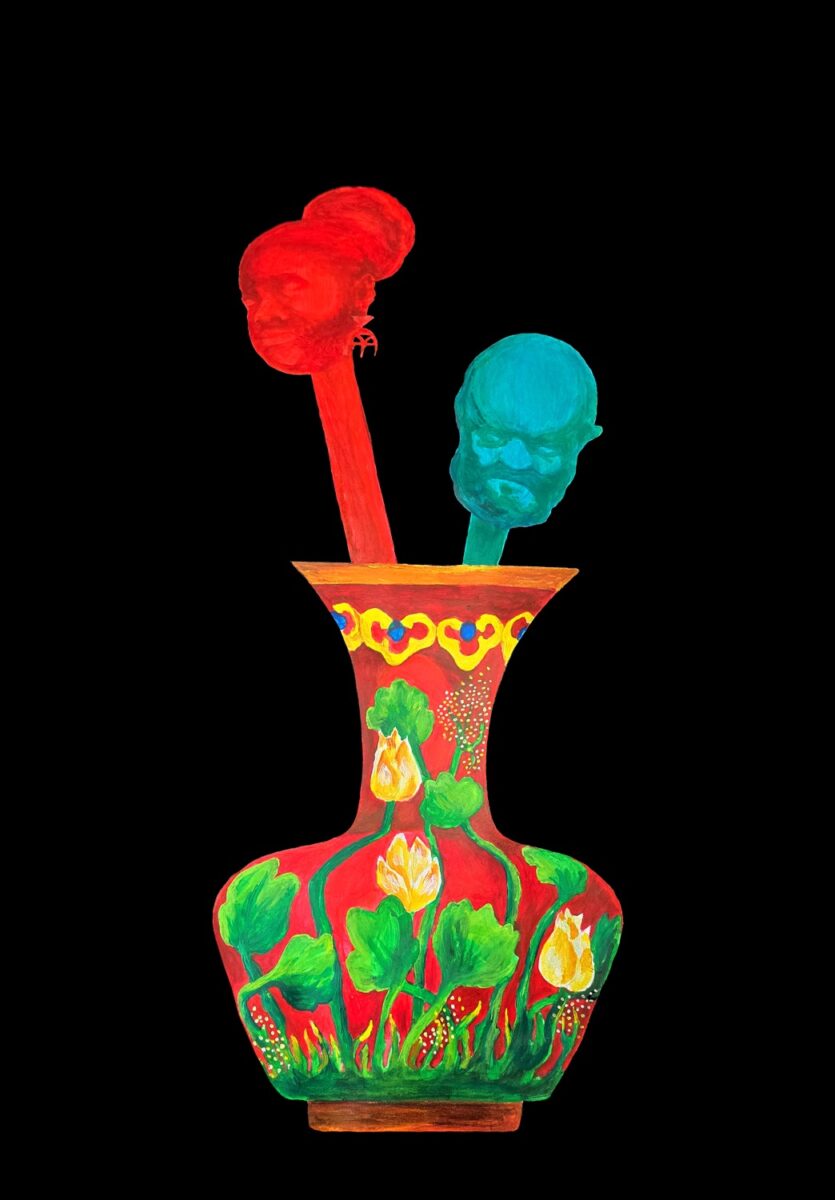

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

138 x 90 cm

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

138 x 90 cm

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

152 x 243 cm

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

152 x 243 cm

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

133 x 79

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

133 x 79

Unique

Raffia "battered", 19th century, textiles, pigments, iroko wood, 720 x 120 cm

[+]

Raffia "battered", 19th century, textiles, pigments, iroko wood, 720 x 120 cm

[-]

Wood, resin, fiberglass, cobaltiferous calcite, heterogenite, coltan, manganese, cassiterite, 260 x 90 cm

Wood, resin, fiberglass, cobaltiferous calcite, heterogenite, coltan, manganese, cassiterite, 260 x 90 cm

Wood, wire mesh, pigments, approx. 200 x 170 cm

[+]

Wood, wire mesh, pigments, approx. 200 x 170 cm

[-]

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

138 x 90 cm

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

152 x 243 cm

Unique

Acrylic on 300g Canson paper

133 x 79

Unique

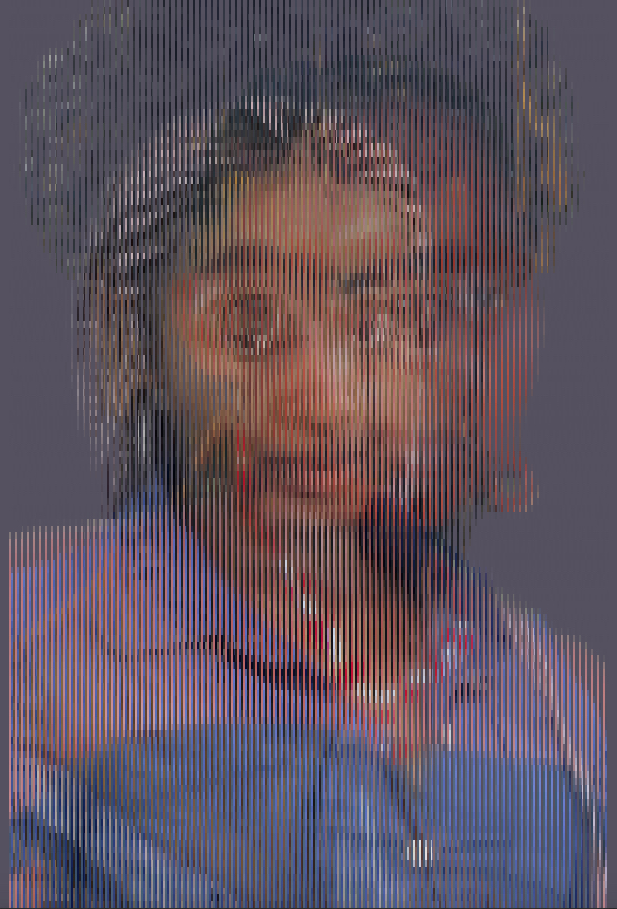

Digital artwork,

https://www.sinzoaanza.nuelschoch.ch/

Raffia "battered", 19th century, textiles, pigments, iroko wood, 720 x 120 cm

Wood, resin, fiberglass, cobaltiferous calcite, heterogenite, coltan, manganese, cassiterite, 260 x 90 cm

Wood, wire mesh, pigments, approx. 200 x 170 cm

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Inkjet print on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (I) to (IV) (A sketch of the city of Manzambi)

Inkjet prints on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Editions of 5 + 1 AP

(…) Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi fait se rencontrer sur quatre grands carrefours de Kinshasa le poète maudit, obstiné et obsédé par une idée de pays où toute idée peut s’exprimer et se réaliser, Matala Mukadi Tshiakatumba, l’artiste aux merveilleuses utopies urbaines Bodys Isek Kingelez et un jeune étudiant kinois anonyme dont l’incontournable radio trottoir raconte qu’il avait proposé un plan de robotique aux fins d’alléger la pénibilité de certains métiers dans la ville, à commencer par la régulation de la circulation routière. L’ébauche de cette rencontre étant elle-même une affirmation tapageuse que ce qui n’est pas est fondamental et indispensable. (…)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (I)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (II)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (III)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (IV)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (I) to (IV) (A sketch of the city of Manzambi)

Inkjet prints on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Editions of 5 + 1 AP

(…) Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi fait se rencontrer sur quatre grands carrefours de Kinshasa le poète maudit, obstiné et obsédé par une idée de pays où toute idée peut s’exprimer et se réaliser, Matala Mukadi Tshiakatumba, l’artiste aux merveilleuses utopies urbaines Bodys Isek Kingelez et un jeune étudiant kinois anonyme dont l’incontournable radio trottoir raconte qu’il avait proposé un plan de robotique aux fins d’alléger la pénibilité de certains métiers dans la ville, à commencer par la régulation de la circulation routière. L’ébauche de cette rencontre étant elle-même une affirmation tapageuse que ce qui n’est pas est fondamental et indispensable. (…)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (I)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (II)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (III)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (IV)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (I) to (IV) (A sketch of the city of Manzambi)

Inkjet prints on Hahnemüle Photo rag baryta paper, 39 x 160 cm

Editions of 5 + 1 AP

(…) Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi fait se rencontrer sur quatre grands carrefours de Kinshasa le poète maudit, obstiné et obsédé par une idée de pays où toute idée peut s’exprimer et se réaliser, Matala Mukadi Tshiakatumba, l’artiste aux merveilleuses utopies urbaines Bodys Isek Kingelez et un jeune étudiant kinois anonyme dont l’incontournable radio trottoir raconte qu’il avait proposé un plan de robotique aux fins d’alléger la pénibilité de certains métiers dans la ville, à commencer par la régulation de la circulation routière. L’ébauche de cette rencontre étant elle-même une affirmation tapageuse que ce qui n’est pas est fondamental et indispensable. (…)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (I)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (II)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (III)

Une esquisse de la ville pour Manzambi (IV)

The lord is dead, long life to the lord, 2019

Mixed-media installation: structure (marine ropes, wooden planks), approx. 280 x 280 x 65 cm, with two mannequins (chasuble, stole, jacket and trousers, shirt, tie, synthetic cotton), variable dimensions; recording, stereo sound, 76 minutes; Photomontage, 150 x 600 cm

Collection Museum Rietberg, Zurich

Exhibition views: Fiktion Kongo, Museum Rietberg, Zurich. © Rainer Wolfsberger

In his work as a writer and artist, Sinzo Aanza has repeatedly dealt with the manifestations of power and injustice in the Congo, from early slavery to colonization to Mobutu’s dictatorship up to the armed conflicts of recent years. At the same time, he goes in search of the little freedoms beyond the reaches of power, for instance, when sapeurs celebrate the sanctity of the oppressed human body.

In his installation The lord is dead, long life to the lord, Sinzo Aanza blends texts of his own with sounds he recorded in villages visited by Himmelheber. By critically questioning European collection practices, he gives the objects and actors back their voices. The result is a kind of theatre performance in which the relationship between the powerful and the powerless, the Self and the Other, is constantly renegotiated.

The lord is dead, long life to the lord, 2019

Mixed-media installation: structure (marine ropes, wooden planks), approx. 280 x 280 x 65 cm, with two mannequins (chasuble, stole, jacket and trousers, shirt, tie, synthetic cotton), variable dimensions; recording, stereo sound, 76 minutes; Photomontage, 150 x 600 cm

Collection Museum Rietberg, Zurich

Exhibition views: Fiktion Kongo, Museum Rietberg, Zurich. © Rainer Wolfsberger

In his work as a writer and artist, Sinzo Aanza has repeatedly dealt with the manifestations of power and injustice in the Congo, from early slavery to colonization to Mobutu’s dictatorship up to the armed conflicts of recent years. At the same time, he goes in search of the little freedoms beyond the reaches of power, for instance, when sapeurs celebrate the sanctity of the oppressed human body.

In his installation The lord is dead, long life to the lord, Sinzo Aanza blends texts of his own with sounds he recorded in villages visited by Himmelheber. By critically questioning European collection practices, he gives the objects and actors back their voices. The result is a kind of theatre performance in which the relationship between the powerful and the powerless, the Self and the Other, is constantly renegotiated.

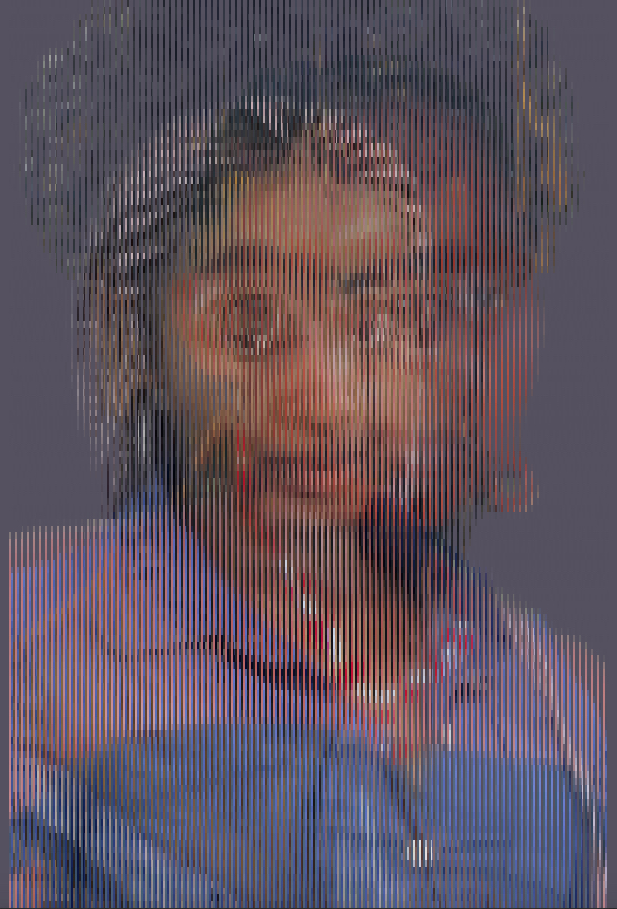

Babola

2018

Inkjet print on satin matte paper

Edition de 3 + 1 EA

This photo is the choice to present a unique testimony of the 2018 Congolese elections. After two and a half years of civil and political protests

to secure the organisation of the vote allowing the first democratic handover in the country’s history, the event is a historical turning point that Sinzo Aanza preferred to examine from the perspective of those who most needed this handover, those whose life and hopes had been weakened, wilted by the political regime about to leave or to renew its mandate through the figure of the dolphin — in the royal meaning of this word. These elections are thereby presented here as the epitome of the relations between the wealthy and the powerful in Congo, and

the figure of the poor as that who endlessly provides.

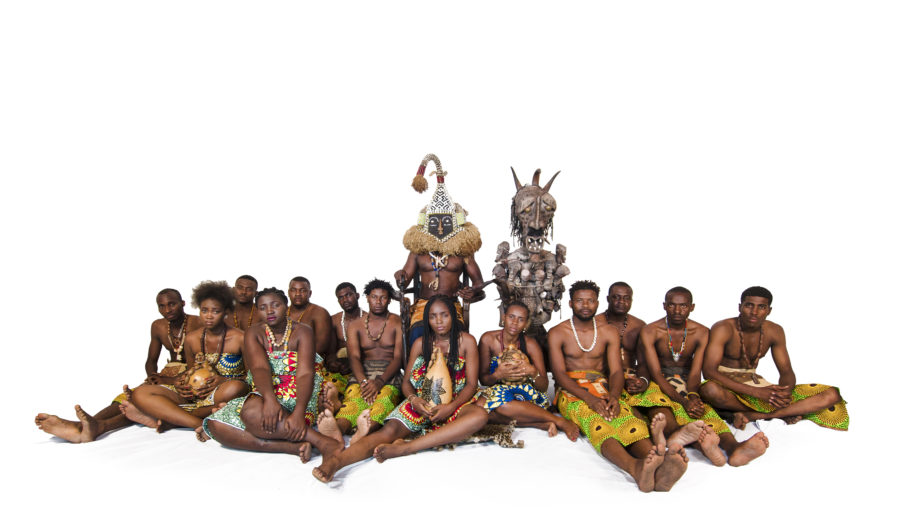

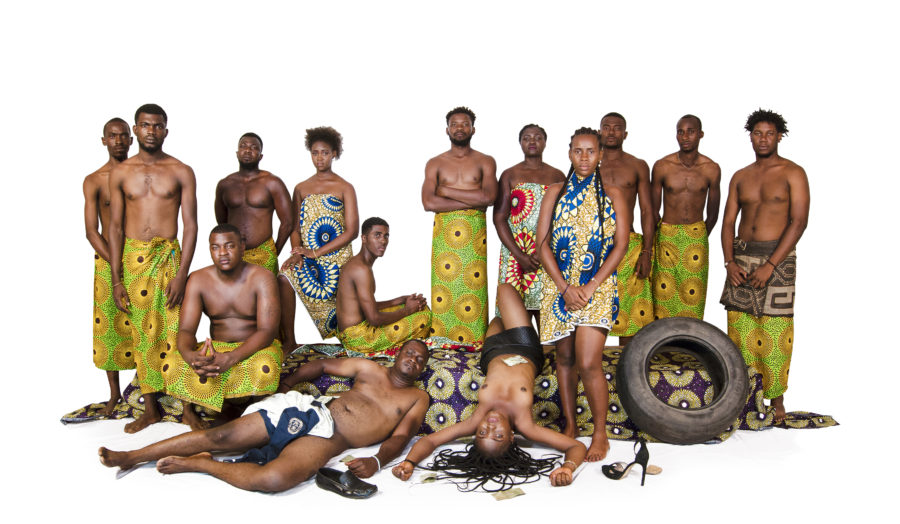

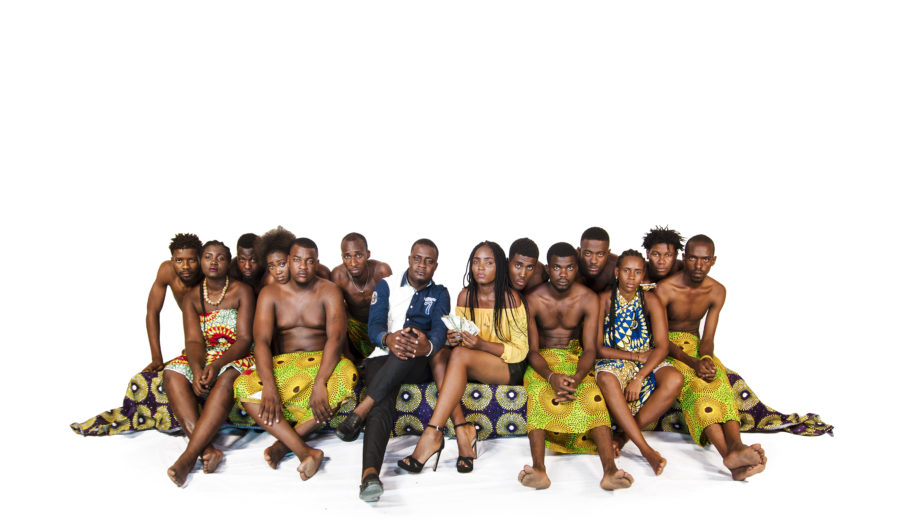

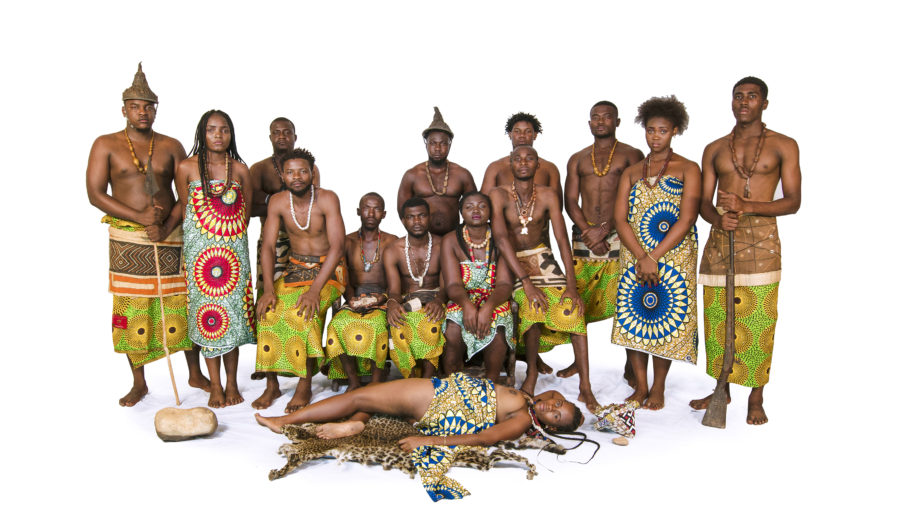

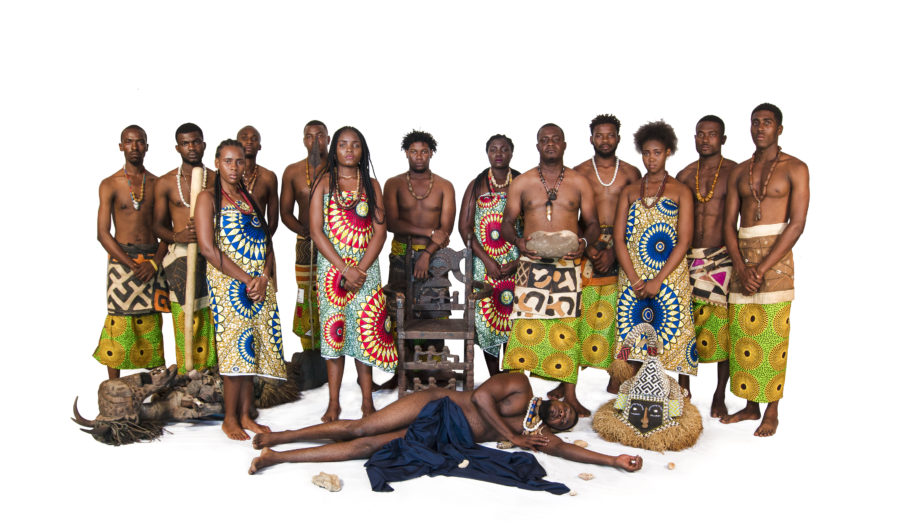

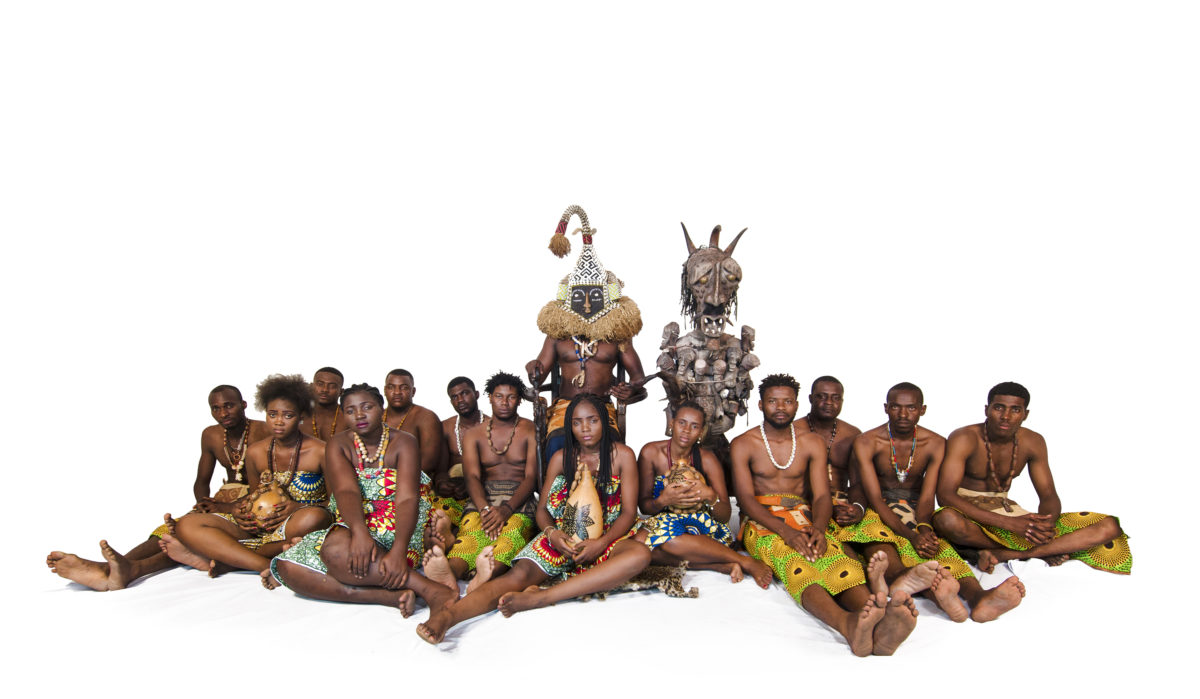

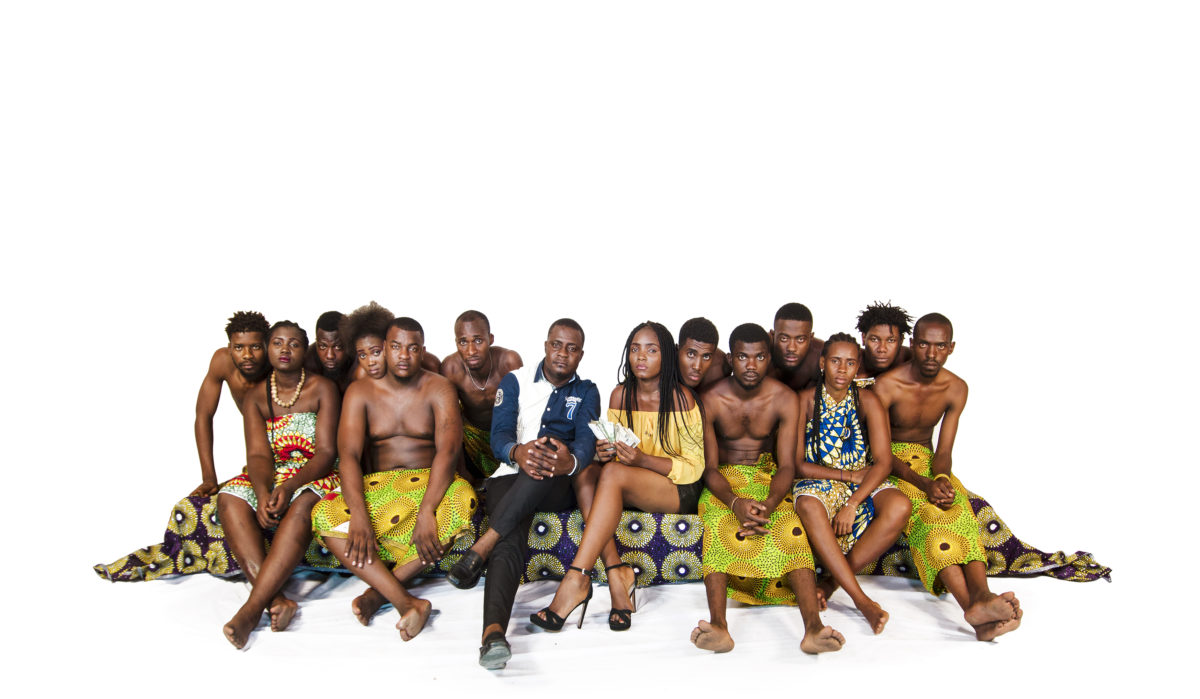

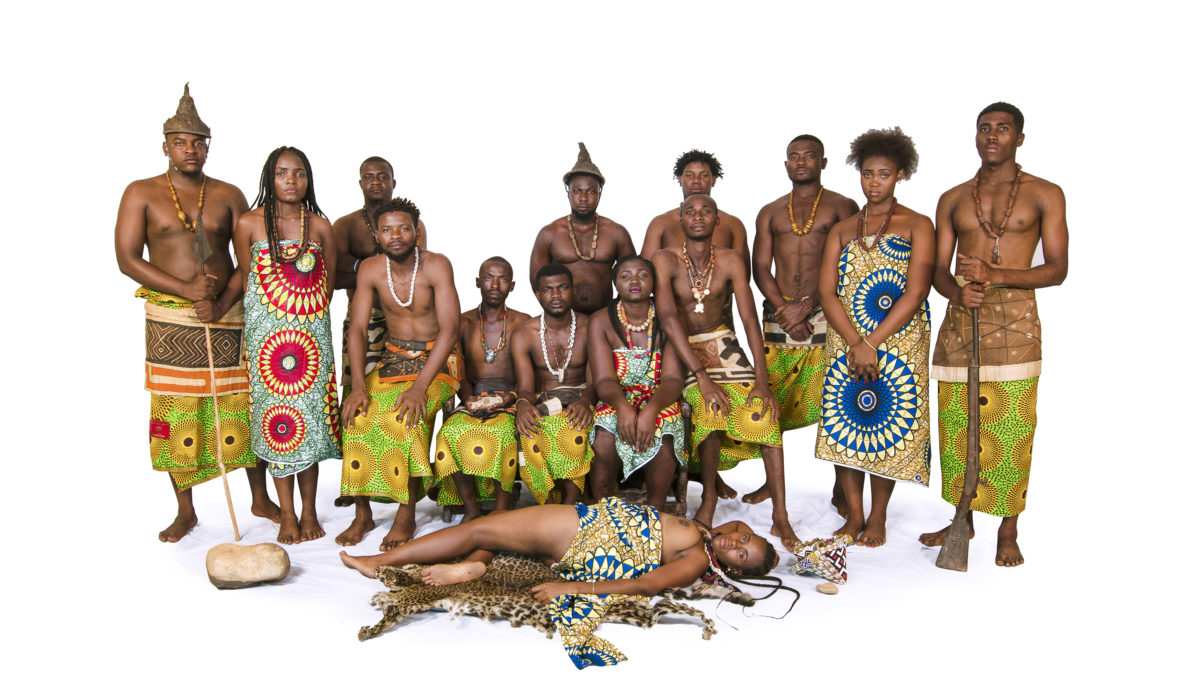

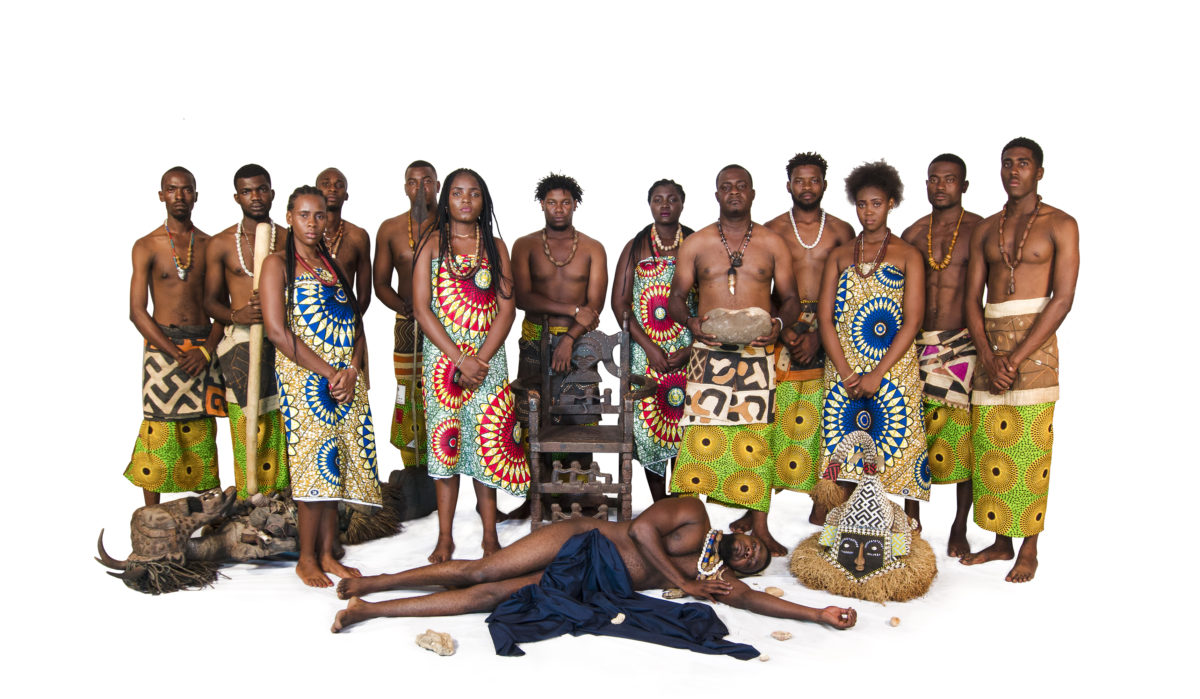

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Untitled (1) – (8)

Eight digital photograph on baryta Photo Rag 315g

80 x 137 cm (each)

Edition of 5 (each)

Untitled, sculpture made of a Kuba mask and a rifle

Untitled, sculpture made of a Tokwe throne, leopard skin and a bat

Untitled, sculpture made of a Songe fetiche and a tire

Untitled, sculptures made of a Kuba headwear, stone, four mannequins wearing Wax suits

Variable dimensions

Unique (installations)

*each photograph is an individual artwork but the ensemble of works also exists as a series of four installations that each comprises two photographs and a sculpture / group of sculptures.

Exhbition views: Pertinences citoyennes, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2018

Exhbition views: Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, WIELS, Bruxelles, 2019. Photo © Alexandra Bertels

Pertinences citoyennes [Social relevances]

A Saga of Humiliations as “National Identity”

The conflicts that plagued DR Congo from 1996 to 2013 fostered the emergence of a collective identification, whereas such ideals and political ideologies as Zairianisation, in other words the call for a return to authenticity, hadn’t been widely accepted by society. Fuelled by nationalist representations since the end of the 1960s, the question of national identity seems to be bogged down in feelings of anger that are expressed in the form of politically motivated lynchings. The exercise of power in its forms of social domination and delegated or self-proclaimed authority, with either a spiritual aura or supported by patronage, is both similar to and far removed from the act of lynching the people who embody these different forms of power. Similar and far-removed because of the dramatic nature of the rhetoric, gestures and actions involved, in short by their language within a framework that is, as far as the powers that be are concerned, symbolically restrained and conversely excessive for lynching.

The unity of Power and Lynching

“You are not yet in power and you beat up people who do not share your opinions. What will happen the day you gain power? What will you do to those who disagree with you? You’ll kill them.”

Antoine Boyamba, former vice-minister for overseas Congolese on Journal Afrique, TV5, sangoyacongoactu, Youtube, 2017.

I have decided to juxtapose two means of expression, on the one hand the expression of feelings of humiliation and bitterness, in addition to the frustration that goes with them, that comprise the origin of national identity in the post-war years and, on the other, the act of lynching those people who embody power as an expression of belonging to the community. I place face to face the calculated and sophisticated language of power and the frenzied, rudimentary language of lynching. Despite its history of wars and the plundering of the country’s natural resources, it seems as if the people of Congo are doomed to fight amongst themselves. Isn’t this fact amply illustrated by the equipment and level of training of the military and police units assigned to protect dignitaries since the creation of a Congolese defence system. Already during the colonial period it was clear that the main mission of the forces of law and order was to control the population and subject it to colonial rule. State institutions are therefore mainly seen as a framework for exercising power, for subduing and controlling and therefore notion of a nation fades away and becomes a distant reality. The nature of these frameworks is such that there is no longer actually any framework and the exercise of power is therefore multiplied and dispersed.

My work is situated in this framework-less space where the language of power and the language of lynching come face to face. It questions the evolution of our society through the prism of these two languages. The reaction of the former vice-minister for overseas Congolese (as quoted above) to the phenomenon of these “combatants”, the young members of the diaspora who use lynching as a means of expression, underlines that these two languages are mutually incomprehensible. Indeed the minister speaks as if the purpose of these young people is to take their turn at being in power and not simply to desecrate the very notion of power, to condemn those who exercise it and throw back in their faces the disgrace and humiliation they feel. I have juxtaposed elements of these languages, placing the elaborate, calculated and sophisticated objects of power alongside the rudimentary, spontaneous and primary objects of lynching. In so doing, I am drawing a picture of political expression in what is a highly precarious context, as well as bringing them together in their common condition, because is not lynching also a way of asserting power?

— Sinzo Aanza, 2018

Projet d’attentat contre l’image ? Acte 3 – Le Royaume des Cieux, 2017

Installation comprises: wooden masks, wooden fetishes, bibles, missives, breviary, chains, audio cassette tapes sound

320 x 1250 cm

Unique

Exhibition views: Rendez-Vous, Biennale de Lyon 2017, Jeune création internationale, Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne, France, 2017. Photo © Blaise Adilon.

Act 3 of the Projet d’attentat contre l’image ? (Project of Assault on the Image ?) constitutes a working step and dwells on the image of the “Kingdom of Heaven”, understood as everything that the Congo is not and that it is called to become, because of its resources in minerals, hydrography, land and men, in a future as distant as it is uncertain. This third act also questions the practices of religion, which characterize and hold back political practices and citizenship, given that religion is, because of a national education elaborated according to colonial references of economy and society, the only place where the strongest convictions are affirmed. The “Kingdom of Heaven”, this utopia brought by the evangelization missions, supported by the colonial administration, is to come, to be prepared, even though the pre-colonial spirituality is sustained by the necessities of present life.

This Act 3 is a sound line of the syncretism that appeared after independence (the evangelization missions being no longer in connivance with the colonial power) between the idea of the “Kingdom of Heaven” and the need to build the present life, notably in the so-called revivalist churches. This Act 3 dares to bring together the tension between the demands of present-day life and the imperative of the Kingdom of Heaven on the one hand, and the tension between national construction and the construction of the individual (notably through practices commonly described as corruption) on the other.

— Sinzo Aanza

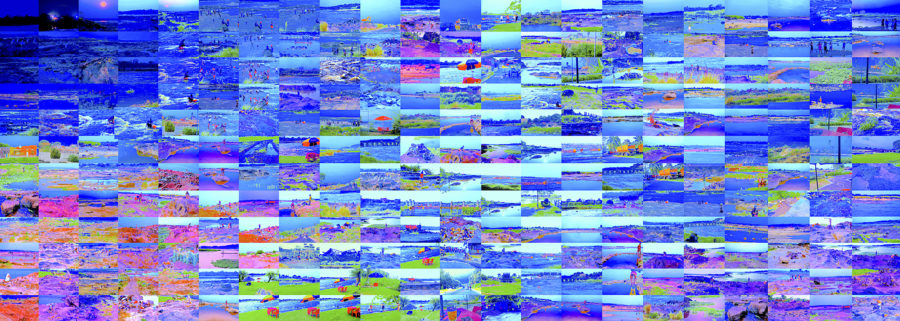

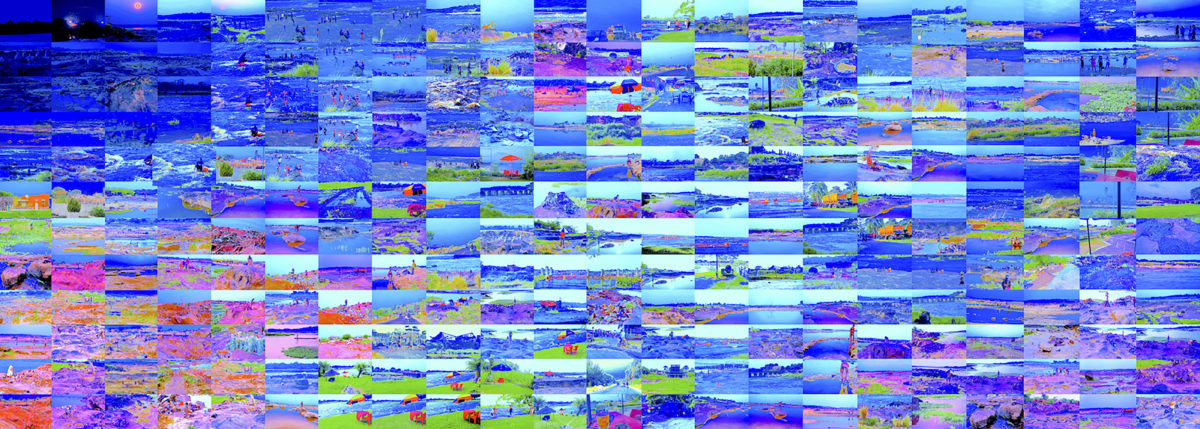

Épreuve d’allégorie, 2017

269 photographs and a sculpture made of stones

240 x 700 cm; variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: MIAM, Sète. Photo © Pierre Schwartz

Épreuve d’allégorie (Allegory Trial) is a postcard featuring images of Kinshasa’s Kinsuka quarter, located in the tourist area of the Congo River rapids.

Above all, it is a journey questioning the concept of value in a place where situations, objects and individuals mingle and merge.

Épreuve d’allégorie was set in the Kinsuka quarter with the aim of creating an ephemeral setting in which to reflect on value and its different forms. It tries to define how, in tourists’ eyes, the value of the Congo River rapids or the relaxing places along its banks, the value of the big gravel plant, the value of the stone breakers’ time and the value of the stone breakers themselves, whose are just becoming part of the scenery, are changing, saying something about society, describing the country and determining an index of powers and illusions.

Text courtesy Rencontres d’Arles