Ali Cherri

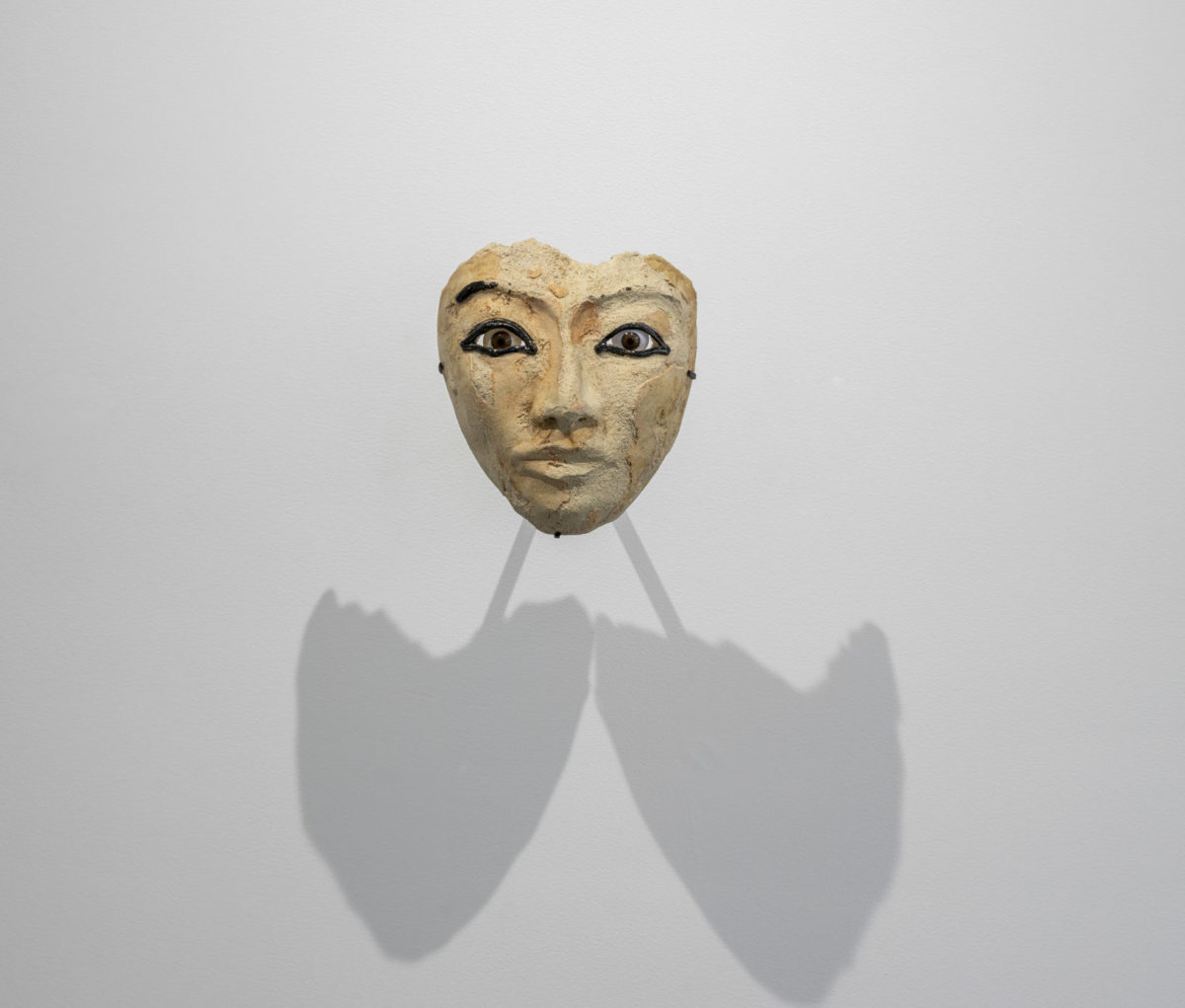

Wrought iron for rain divination in the shape of snakes (Nigeria, Mumuye people), sarcophagus mask (Egypt, 1st millennium BC), pair of eyes from a limestone sarcophagus (Egypt, Late Period or earlier), concrete

93 x 46 x 30 cm

Unique

Wrought iron for rain divination in the shape of snakes (Nigeria, Mumuye people), sarcophagus mask (Egypt, 1st millennium BC), pair of eyes from a limestone sarcophagus (Egypt, Late Period or earlier), concrete

93 x 46 x 30 cm

Unique

Installation of jesmonite ears mounted on a wooden base

220 x 110 x 10 cm

Unique

Installation of jesmonite ears mounted on a wooden base

220 x 110 x 10 cm

Unique

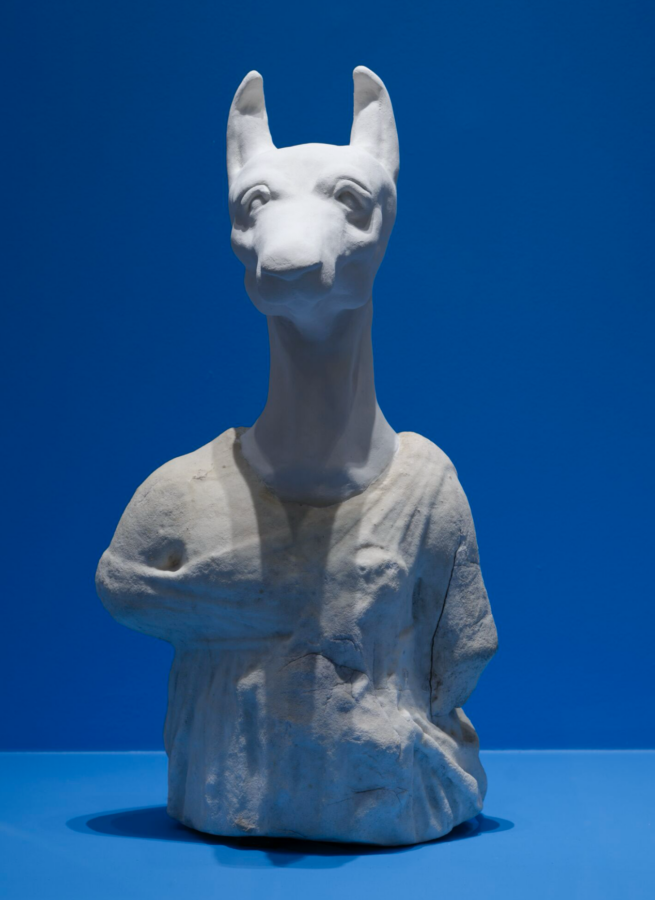

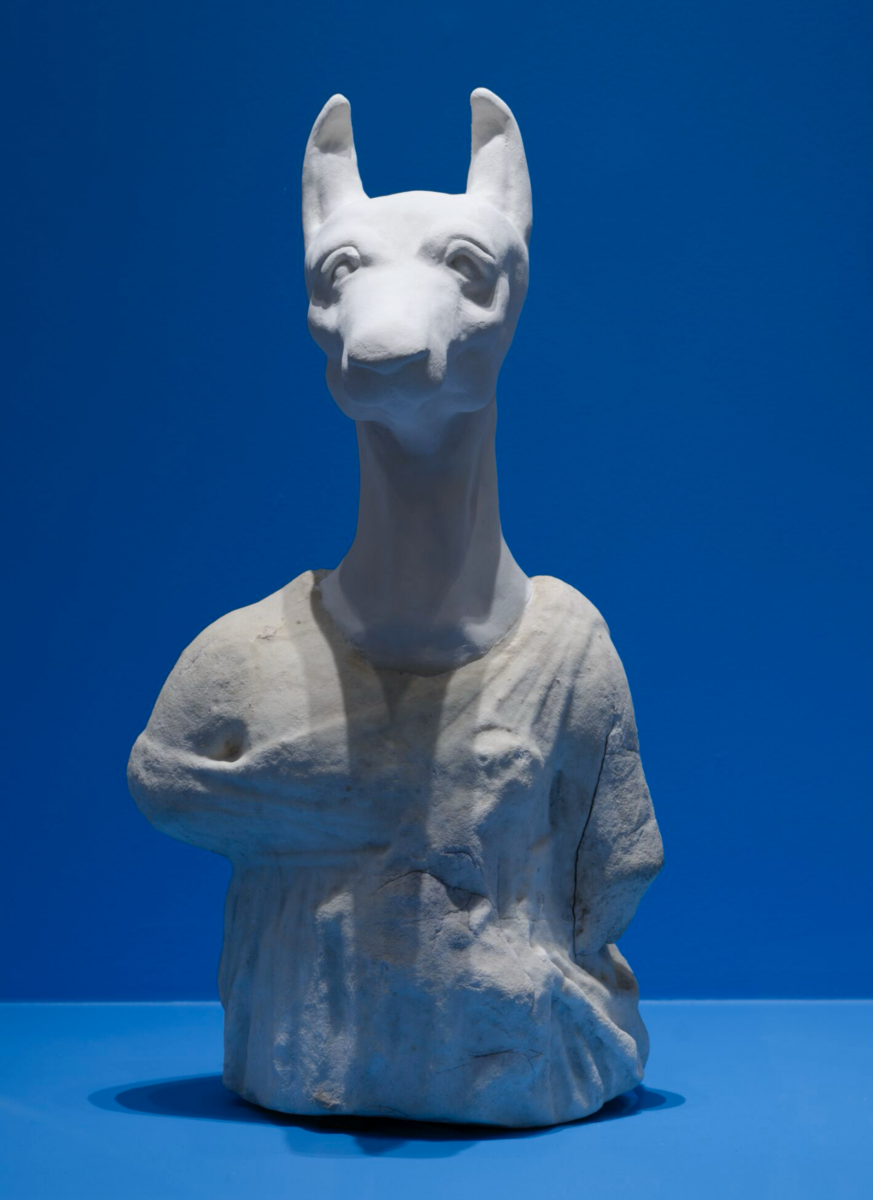

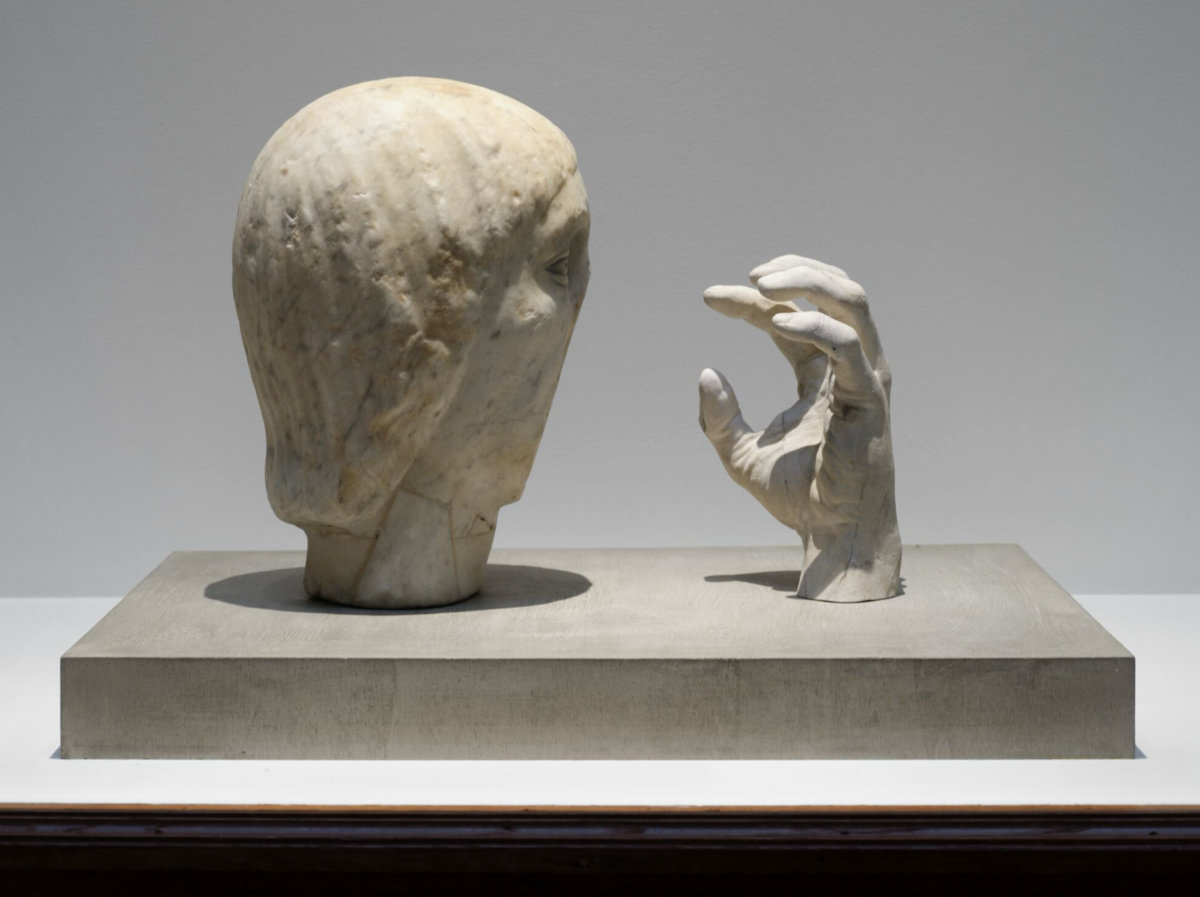

Acephalous bust in marble from the Roman period, epoxy paste, steel, coating

59 x 29 x 27 cm

Unique

Acephalous bust in marble from the Roman period, epoxy paste, steel, coating

59 x 29 x 27 cm

Unique

Pair of buffalo horns (Bubalus bubalis, not regulated), wood, instrument strings, steel, concrete

90 x 70 x 46 cm

Unique

Pair of buffalo horns (Bubalus bubalis, not regulated), wood, instrument strings, steel, concrete

90 x 70 x 46 cm

Unique

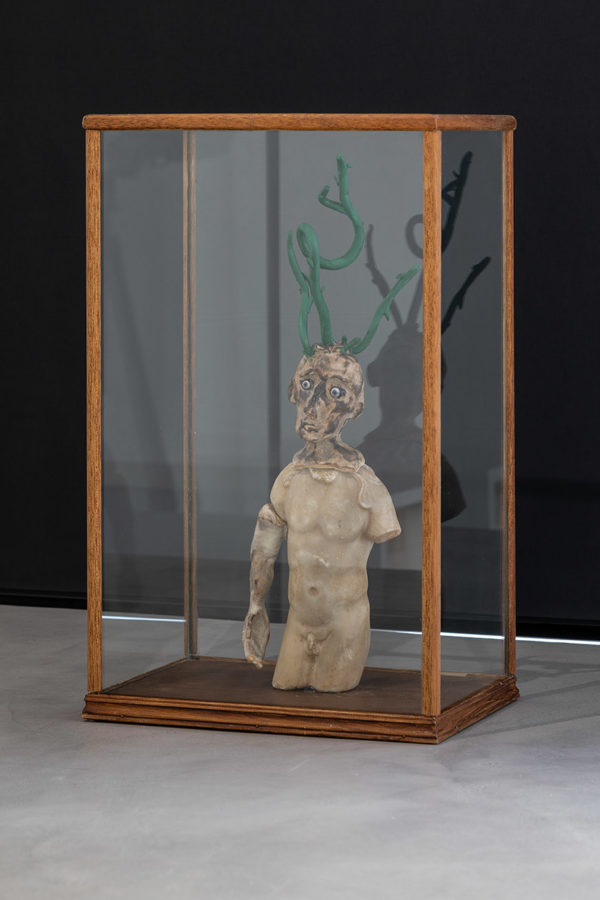

Epoxy paste, coating, naturalized throat red, concrete, glass

49,5 x 50 x 35 cm

Unique

Epoxy paste, coating, naturalized throat red, concrete, glass

49,5 x 50 x 35 cm

Unique

Pair of bronze and alabaster sarcophagus eyes from a sarcophagus mask (Egypt, Saite (663-525 BC) or Late Period), brass serving tray, brass

26 x 42 x 33 cm

Unique

Pair of bronze and alabaster sarcophagus eyes from a sarcophagus mask (Egypt, Saite (663-525 BC) or Late Period), brass serving tray, brass

26 x 42 x 33 cm

Unique

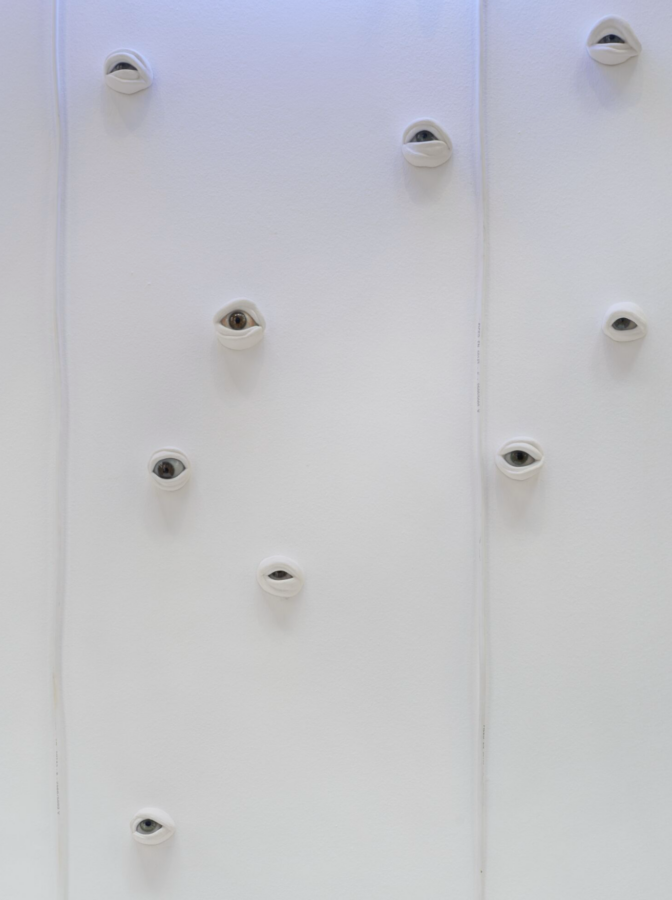

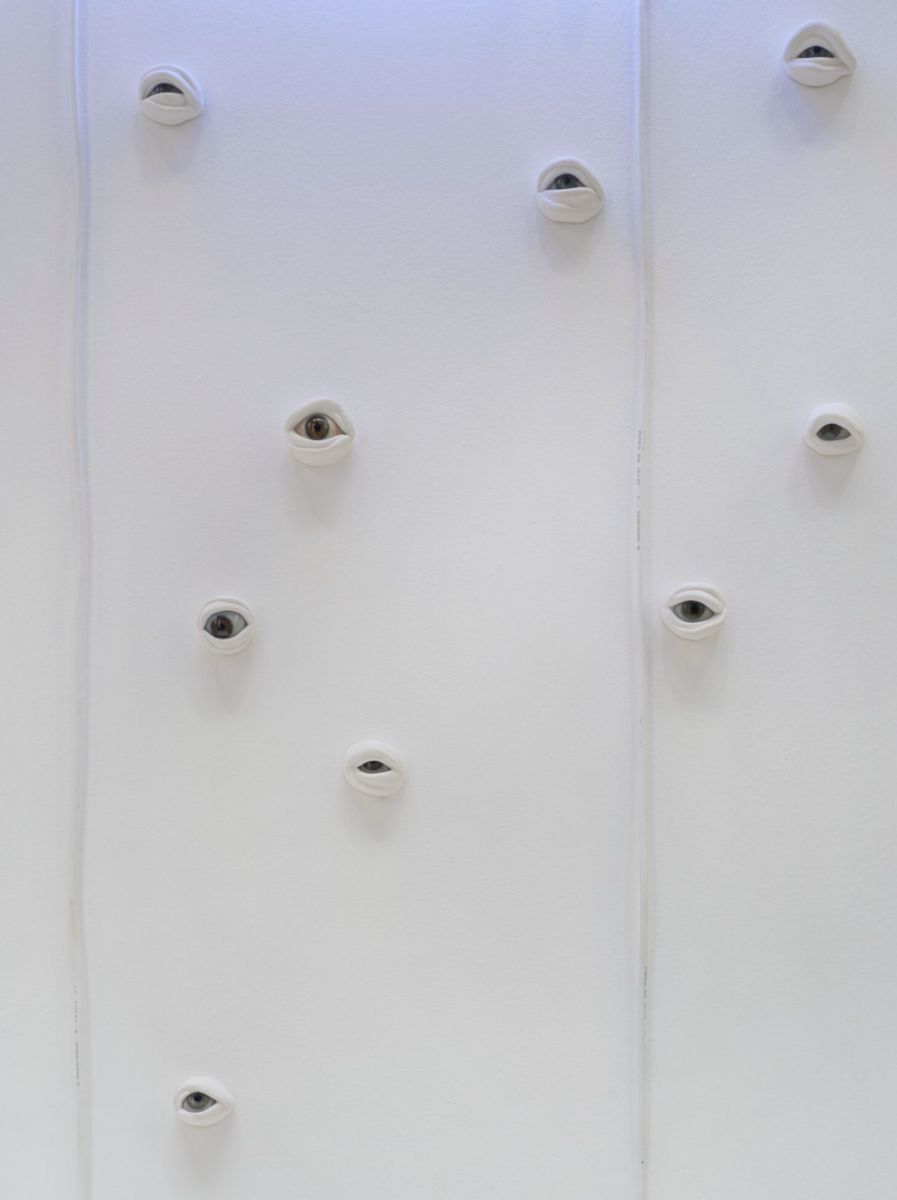

installation of 30 eyes (glass, epoxy, coated prosthetic eyes), neon (ContreChamp)

220 x 110 x 10 cm

Unique

installation of 30 eyes (glass, epoxy, coated prosthetic eyes), neon (ContreChamp)

220 x 110 x 10 cm

Unique

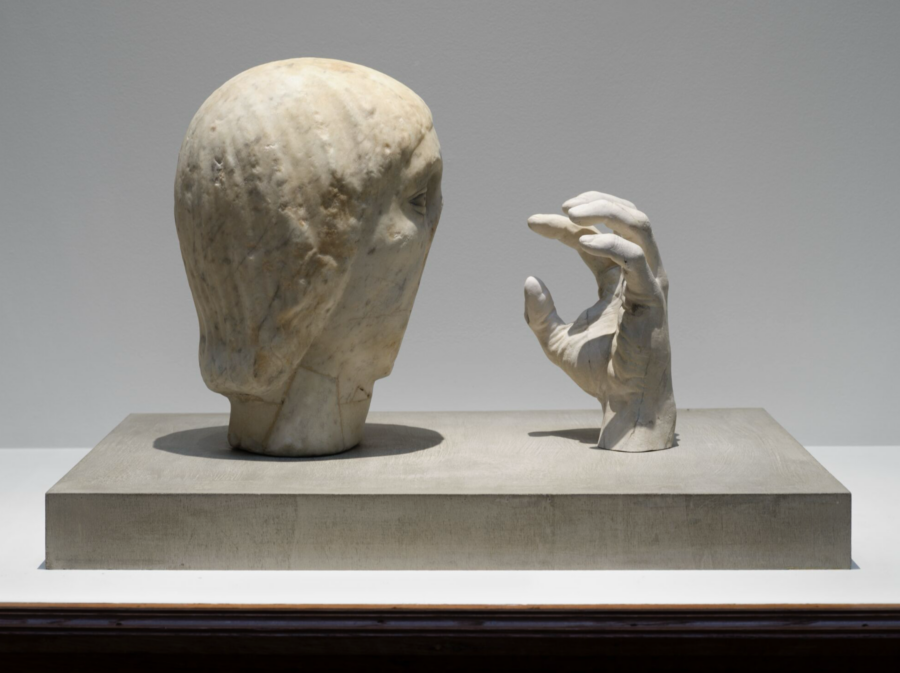

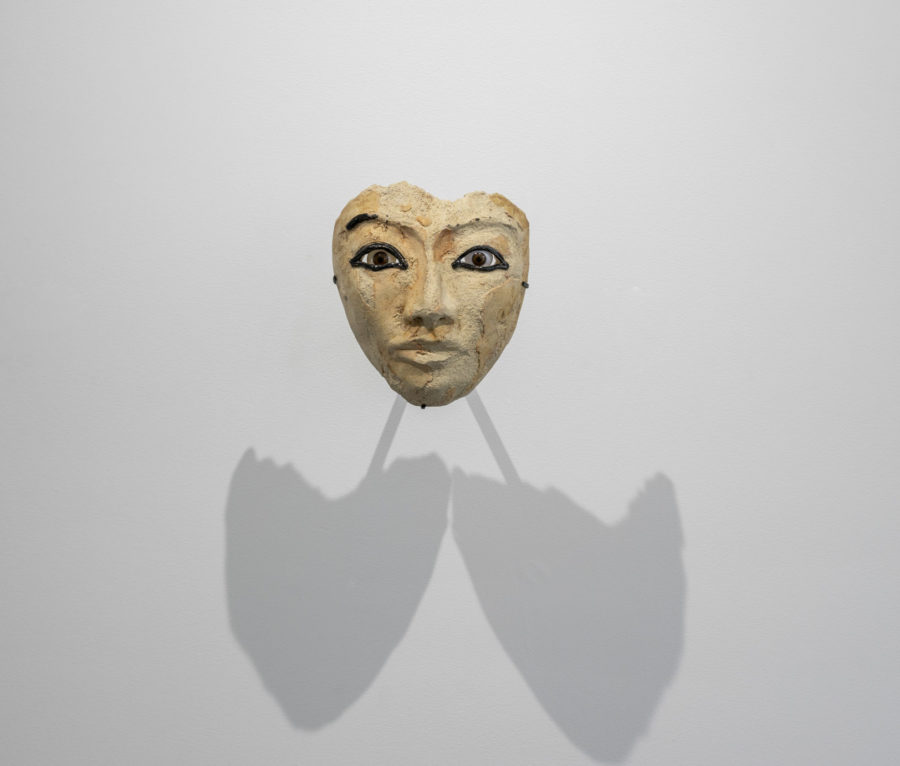

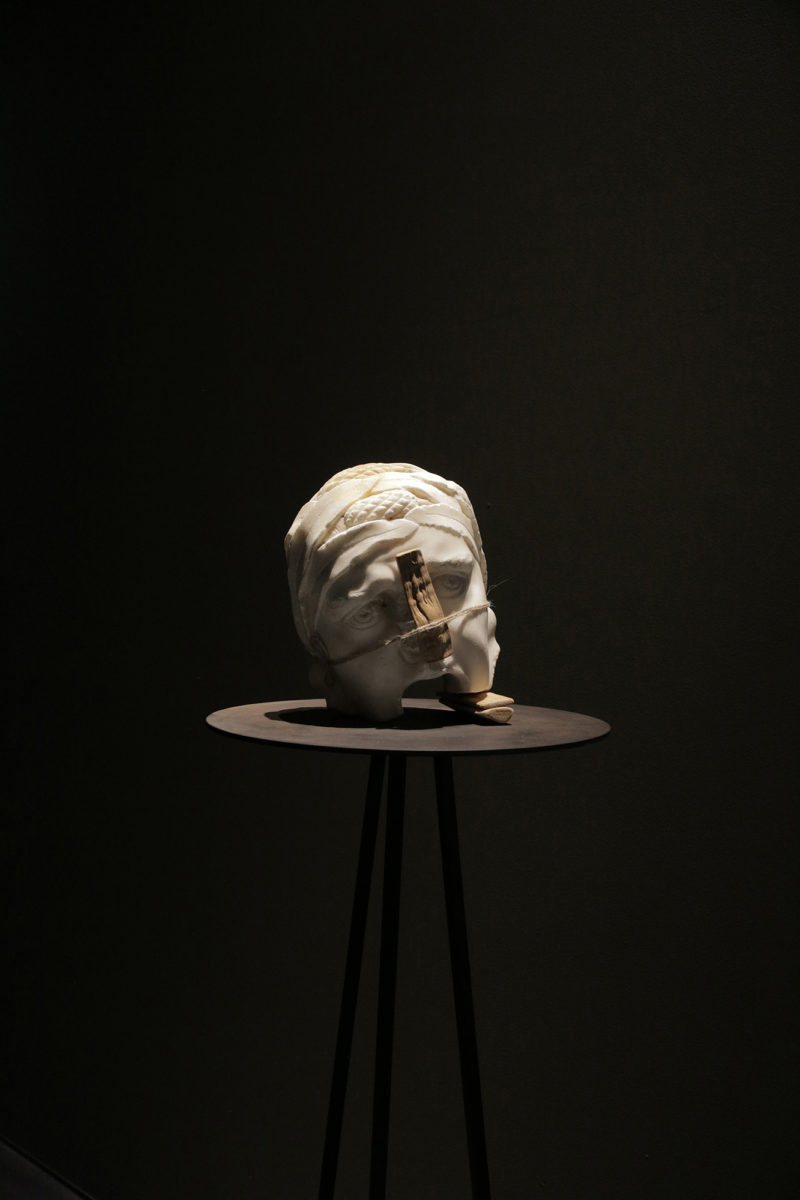

Byzantine-period marble head, lower part of face missing, jesmonite, concrete, steel, wood

Unique

Byzantine-period marble head, lower part of face missing, jesmonite, concrete, steel, wood

Unique

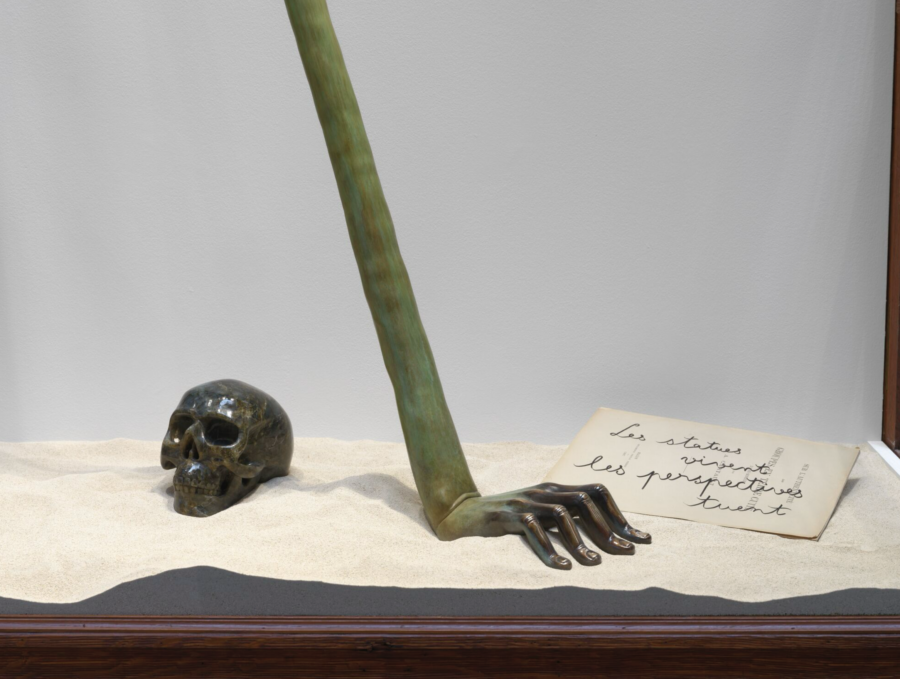

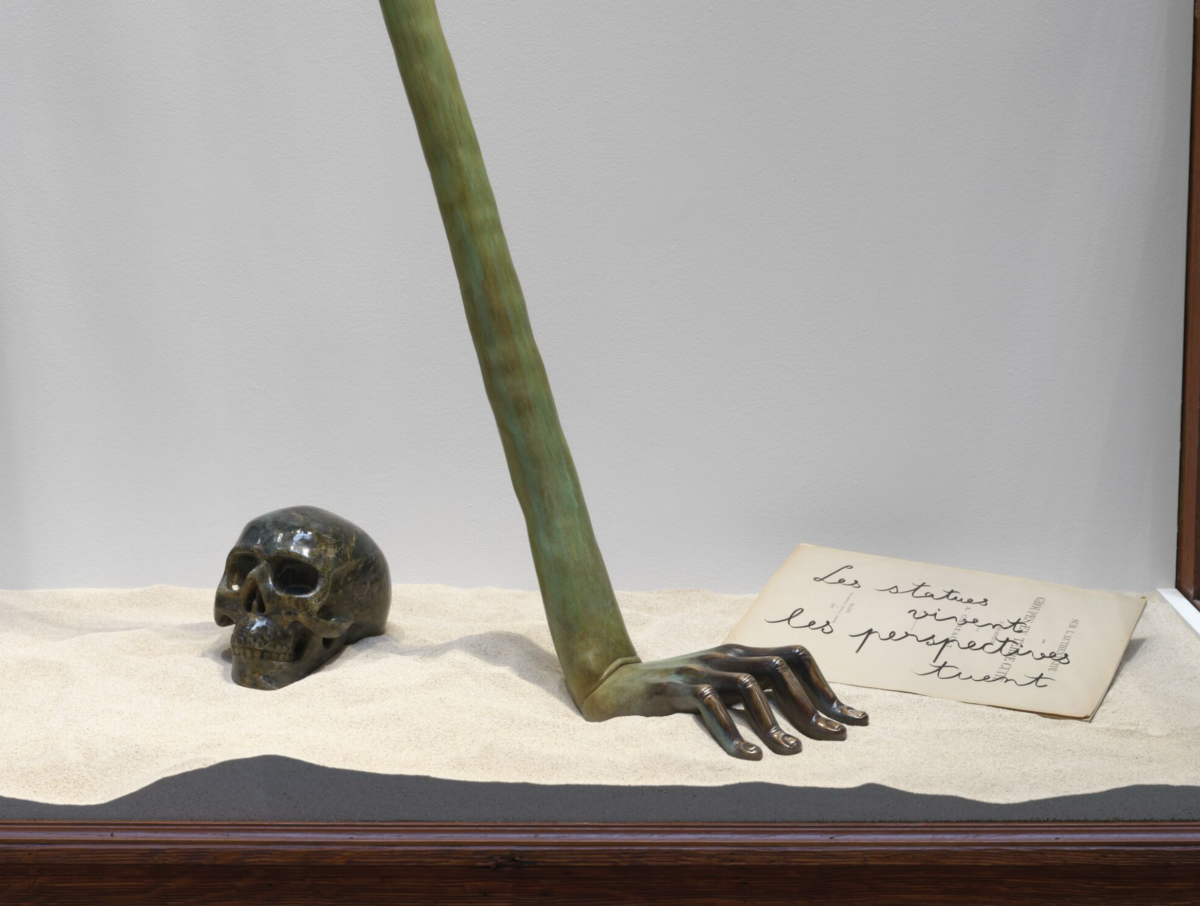

Memento mori in sculpted labradorite, patinated bronze, calligraphy on paper

Unique

Memento mori in sculpted labradorite, patinated bronze, calligraphy on paper

Unique

Patinated bronze

Variable dimensions

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Patinated bronze

Variable dimensions

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

8 x 11,5 x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

8 x 11,5 x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

22 x 29 x 35 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

22 x 29 x 35 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

52 x 20 x 10,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1EA

Bronze

52 x 20 x 10,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1EA

Bronze

23,5 x 16,5 x 7,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

23,5 x 16,5 x 7,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

3 x 9 x 3,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

3 x 9 x 3,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

23,5 x 20 x 14,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

23,5 x 20 x 14,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

20 x 16 x 8 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

20 x 16 x 8 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

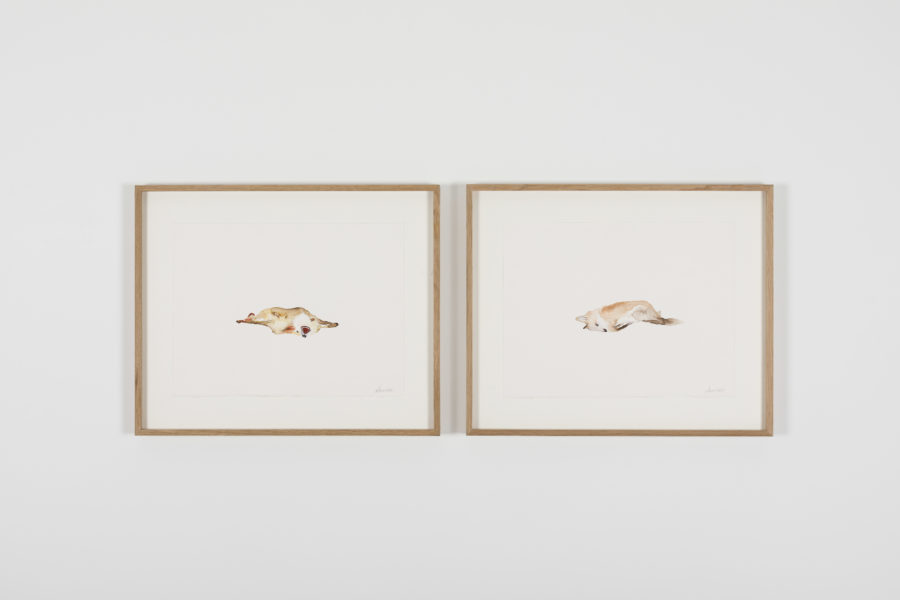

A series of 8 watercolor and graphite on paper, framed

45,2 x 35,8 x 4 cm (each)

Unique

A series of 8 watercolor and graphite on paper, framed

45,2 x 35,8 x 4 cm (each)

Unique

Watercolor and graphite on paper, framed

45,2 x 35,8 x 4 cm

Unique

Watercolor and graphite on paper, framed

45,2 x 35,8 x 4 cm

Unique

Waxed bronze, wood, steel, clay, sand, pigments

168 x 29 x 29

Unique

Waxed bronze, wood, steel, clay, sand, pigments

168 x 29 x 29

Unique

Steel base, KODAK 35 mm Film and Slide Viewer 6 minutes loop

114 x 33 x 33 cm

Unique

Steel base, KODAK 35 mm Film and Slide Viewer 6 minutes loop

114 x 33 x 33 cm

Unique

Patinated bronze, steel, clay, sand, wood, epoxy paste, pigments

267 x 181 x 81 cm

Unique

Patinated bronze, steel, clay, sand, wood, epoxy paste, pigments

267 x 181 x 81 cm

Unique

Patinated bronze, steel, clay, sand, wood, plaster, pigments

234 x 77 x 115 cm

Unique

Patinated bronze, steel, clay, sand, wood, plaster, pigments

234 x 77 x 115 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, concrete, plaster, clay, sand, epoxy paste, pigments

76 x 82 x 60 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, concrete, plaster, clay, sand, epoxy paste, pigments

76 x 82 x 60 cm

Unique

Marble divinity head from Roman period; steel, plaster

53 x 21 x 11 cm

Unique

Marble divinity head from Roman period; steel, plaster

53 x 21 x 11 cm

Unique

bronze, steel

240 x 83 x 74 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

bronze, steel

240 x 83 x 74 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Ocular implants made of glass, Wood, Steel, Epoxy Paste, Coating

24 x 30 x 18 cm

Unique

Ocular implants made of glass, Wood, Steel, Epoxy Paste, Coating

24 x 30 x 18 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, sand, clay, pigments

42 x 21 x 19 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, sand, clay, pigments

42 x 21 x 19 cm

Unique

Terracotta water buffalo from the Han period; wood, steel, brass, plaster, glazed stoneware

42 x 29 x 12 cm

Unique

Terracotta water buffalo from the Han period; wood, steel, brass, plaster, glazed stoneware

42 x 29 x 12 cm

Unique

Steel, sand, clay, pigments

18 x 41 x 21 cm

Unique

Steel, sand, clay, pigments

18 x 41 x 21 cm

Unique

Female marble face (17th century); marble draped fragment from Roman period; pair of hand-shaped clappers in the New Kingdom or 3rd Intermediate Period style; steel, wood

77 x 25 x 22 cm

Unique

Female marble face (17th century); marble draped fragment from Roman period; pair of hand-shaped clappers in the New Kingdom or 3rd Intermediate Period style; steel, wood

77 x 25 x 22 cm

Unique

Pprosthetic glass eyes, wood veneered in walnut bur, golden leaf, brass, resin

25 x 20 x 20 cm

Unique

Pprosthetic glass eyes, wood veneered in walnut bur, golden leaf, brass, resin

25 x 20 x 20 cm

Unique

Idol with pinched nose (Indus Valley); golden leaf, steel, wood, coating

10 x 8 x 8 cm

Unique

Idol with pinched nose (Indus Valley); golden leaf, steel, wood, coating

10 x 8 x 8 cm

Unique

Glazed stoneware, concrete, coting

27 x 11 x 11 cm

Unique

Glazed stoneware, concrete, coting

27 x 11 x 11 cm

Unique

Stone head from the 14th/15th century, carved, with flat and smooth eyes to evoke the ancient tradition of depositing a coin in the eyes of a dead man, patinated silver, plaster, steel

49 x 41 x 31 cm

Unique

Stone head from the 14th/15th century, carved, with flat and smooth eyes to evoke the ancient tradition of depositing a coin in the eyes of a dead man, patinated silver, plaster, steel

49 x 41 x 31 cm

Unique

Egyptian head from an antique sarcophagus, probably Late Empire; steel, wood, coating, sand, pigments, glue

152 x 24 x 50 cm

Unique

Egyptian head from an antique sarcophagus, probably Late Empire; steel, wood, coating, sand, pigments, glue

152 x 24 x 50 cm

Unique

Plaster skull, wood, plaster, brass, glue

28 x 18 x 40 cm

Unique

Plaster skull, wood, plaster, brass, glue

28 x 18 x 40 cm

Unique

Wood, plaster, brass, glue

23 x 15 x 15 cm

Unique

Wood, plaster, brass, glue

23 x 15 x 15 cm

Unique

Ocular prostheses in glass, wood, brass, epoxy paste, coating

21 x 13 x 8,5 cm

Unique

Ocular prostheses in glass, wood, brass, epoxy paste, coating

21 x 13 x 8,5 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, epoxy paste, coating

33 x 12 x x 12 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, epoxy paste, coating

33 x 12 x x 12 cm

Unique

HD video, colour, sound, 25’58’’

[+]HD video, colour, sound, 25’58’’

[-]Paint on fabric, aluminium scaffolding

[+]Paint on fabric, aluminium scaffolding

[-]Resin, pigments, iron, clay

[+]Resin, pigments, iron, clay

[-]Clay, sand, XPS, wood, pigments, iron

[+]Clay, sand, XPS, wood, pigments, iron

[-]Carved stone, clay, sand, XPS, wood, pigments, iron

[+]Carved stone, clay, sand, XPS, wood, pigments, iron

[-]Resin, fiberglass, clay, sand, XPS, pigments, iron

[+]Resin, fiberglass, clay, sand, XPS, pigments, iron

[-]Iron-cast mask, wood, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Iron-cast mask, wood, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Zoomorphic stone head; iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Zoomorphic stone head; iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Animal mask, iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Animal mask, iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Old wooden mask; iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments / Bull horns, iron, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Old wooden mask; iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments / Bull horns, iron, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Terracotta Nok head (Nigeria, c. 500

B.C.), clay, sand, xps, wood, pigments

88 x 25 x 40 cm

Terracotta Nok head (Nigeria, c. 500

B.C.), clay, sand, xps, wood, pigments

88 x 25 x 40 cm

Pink Sandstone of a roaring lion head

sculpture (England, 16th century), clay,

sand, foam, xps, pigments

52 x 105 x 45 cm

Pink Sandstone of a roaring lion head

sculpture (England, 16th century), clay,

sand, foam, xps, pigments

52 x 105 x 45 cm

Heaume mask Mapico (Tanzania), clay,

sand, xps, wood, pigments

130 x 85 x 67 cm

Heaume mask Mapico (Tanzania), clay,

sand, xps, wood, pigments

130 x 85 x 67 cm

Gurunsi Monkey Mask, first half of the 20th century, (Burkina Faso), clay sand, xps, pigments

78 x 78 x 78 cm

Unique

Gurunsi Monkey Mask, first half of the 20th century, (Burkina Faso), clay sand, xps, pigments

78 x 78 x 78 cm

Unique

Vakono Monkey Mask, first half of the 20th century, (Nigeria), clay sand, xps, pigments

106 x 78 x 48 cm

Unique

Vakono Monkey Mask, first half of the 20th century, (Nigeria), clay sand, xps, pigments

106 x 78 x 48 cm

Unique

Male head with ball headdress (Egypt, Late Period, ca. 664-32 B.C.), clay, sand, pigments, xps, steel

50 x 12 x 8 cm

Unique

Male head with ball headdress (Egypt, Late Period, ca. 664-32 B.C.), clay, sand, pigments, xps, steel

50 x 12 x 8 cm

Unique

Three-channel video installation,

18 min 48 sec (in loop)

Three-channel video installation,

18 min 48 sec (in loop)

Mayan head of a dignitary in orangebeige

terracotta (Mexico or Guatemala,

Classical period, 600-900 AD) , clay, sand,

loam, gesso, pencil, and pigments

160 x 40 x 140 cm

Mayan head of a dignitary in orangebeige

terracotta (Mexico or Guatemala,

Classical period, 600-900 AD) , clay, sand,

loam, gesso, pencil, and pigments

160 x 40 x 140 cm

Front part of a Mayan cult vase modeled

after a priest wearing a mouth mask

evoking the Monkey God Hun Batz or Hun

Chouen, terracotta with smoothed orange

engobe (Classical period, 600-900 AD),

clay, sand, loam, gesso, pencil, pigments

198 x 70 x 50 cm

Front part of a Mayan cult vase modeled

after a priest wearing a mouth mask

evoking the Monkey God Hun Batz or Hun

Chouen, terracotta with smoothed orange

engobe (Classical period, 600-900 AD),

clay, sand, loam, gesso, pencil, pigments

198 x 70 x 50 cm

Terracotta Nok head (Nigeria, c. 2100 B.C.),

clay, sand, loam, gesso, pencil, pigments

180 x 75 x 50 cm

Terracotta Nok head (Nigeria, c. 2100 B.C.),

clay, sand, loam, gesso, pencil, pigments

180 x 75 x 50 cm

Photo © The National Gallery

[+]Photo © The National Gallery

[-]Photo © The National Gallery

[+]Photo © The National Gallery

[-]Photo © The National Gallery

[+]Photo © The National Gallery

[-]Photo © The National Gallery

[+]Photo © The National Gallery

[-]Photo © The National Gallery

[+]Photo © The National Gallery

[-]Amulet of the Egyptian falcon god Horus in glass paste (Ancient Egypt, Late Period), glazed stoneware, 17,5 x 13,5 x 7,8 cm

[+]Amulet of the Egyptian falcon god Horus in glass paste (Ancient Egypt, Late Period), glazed stoneware, 17,5 x 13,5 x 7,8 cm

[-]Terracotta statuette head representing a veiled woman (Hellenistic period, Cyprus), small animal head in green stone (Pre-Columbian America), glazed stoneware, wood, 24,5 x 23 x 12,5 cm

[+]Terracotta statuette head representing a veiled woman (Hellenistic period, Cyprus), small animal head in green stone (Pre-Columbian America), glazed stoneware, wood, 24,5 x 23 x 12,5 cm

[-]Beads, cylindrical face in glass paste (Phoenicia, 1st millennium B.C.), coral branch, glazed stoneware, 23 x 12,7 x 19,5 cm

[+]Beads, cylindrical face in glass paste (Phoenicia, 1st millennium B.C.), coral branch, glazed stoneware, 23 x 12,7 x 19,5 cm

[-]19th century torso of Apollo in marble, beads decorated with eyes in glass paste (Ancient period, Mediterranean basin), glazed stoneware, 50 x 31 x 20,5 cm

[+]19th century torso of Apollo in marble, beads decorated with eyes in glass paste (Ancient period, Mediterranean basin), glazed stoneware, 50 x 31 x 20,5 cm

[-]Carved wooden mask with remains of polychromy (Late Period, 7th – 4th century B.C.), glazed stoneware, 50 x 28 x 21 cm

[+]Carved wooden mask with remains of polychromy (Late Period, 7th – 4th century B.C.), glazed stoneware, 50 x 28 x 21 cm

[-]Pair of ocular protheses in glass, moulding in glazed stoneware, 15 x 16 x 21 cm

[+]Pair of ocular protheses in glass, moulding in glazed stoneware, 15 x 16 x 21 cm

[-]Fragment of a 19th century white Roman marble sculpture with legs and feet (human size); antique Egyptian bronze eyes with matching eyebrows, remains of azurite and inlays; feathered headdress from Angola (Tchokwe culture); glazed stoneware and metal, 130 x 63 x 51 cm

[+]Fragment of a 19th century white Roman marble sculpture with legs and feet (human size); antique Egyptian bronze eyes with matching eyebrows, remains of azurite and inlays; feathered headdress from Angola (Tchokwe culture); glazed stoneware and metal, 130 x 63 x 51 cm

[-]Watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed)

[+]Watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed)

[-]Diptych, watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

[+]Diptych, watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

[-]Diptych, watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

[+]Diptych, watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

[-]Twelve drawings, watercolor and graphite on paper, 50 x 41,5 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

[+]Twelve drawings, watercolor and graphite on paper, 50 x 41,5 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

[-]19th century patented bronze Sphinx, taxidermy bird, red colorant, 40 x 100 x 40 cm

[+]19th century patented bronze Sphinx, taxidermy bird, red colorant, 40 x 100 x 40 cm

[-]Taxidermy porcupine fish, 20th century, pole from Salampasu village, anthropomorphic wooden head, metal rod, wood and neoprene tube, 160 x 60 x 50 cm

[+]Taxidermy porcupine fish, 20th century, pole from Salampasu village, anthropomorphic wooden head, metal rod, wood and neoprene tube, 160 x 60 x 50 cm

[-]19th century wooden pole leg, taxidermy Falco Subbuteo, Chinese dragon head in porcelain, metal rod and wood, 60 x 40 x 40 cm

[+]19th century wooden pole leg, taxidermy Falco Subbuteo, Chinese dragon head in porcelain, metal rod and wood, 60 x 40 x 40 cm

[-]Osteological Ceratogymna atrata, Salampasu head mask from Central Africa, wooden base, 100 x 40 x 40 cm

[+]Osteological Ceratogymna atrata, Salampasu head mask from Central Africa, wooden base, 100 x 40 x 40 cm

[-]Lightbox, Duratrans print ; 200 x 125 x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1 AP

Lightbox, Duratrans print ; 200 x 125 x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1 AP

Tête d’Eros, marbre; figurine de protection Lobi du Burkina Faso enois; aile de geai séchée ; 50 x 15 x 15 cm

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Jameel Art Center, Dubai, 2019.

Tête d’Eros, marbre; figurine de protection Lobi du Burkina Faso enois; aile de geai séchée ; 50 x 15 x 15 cm

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Jameel Art Center, Dubai, 2019.

Terracotta statue representing a sphinx, Nok Civilization, 500 BC approx., head of a roe deer in taxidermy, 1950

[+]Terracotta statue representing a sphinx, Nok Civilization, 500 BC approx., head of a roe deer in taxidermy, 1950

[-]Tête en marbre, 18e siècle, bois, ficelle, trépied en métal ; 130 x 40 x 40 cm

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Jameel Art Center, Dubai, 2019.

Tête en marbre, 18e siècle, bois, ficelle, trépied en métal ; 130 x 40 x 40 cm

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Jameel Art Center, Dubai, 2019.

Headless sandstone bust of St. John the Baptist, (France, late 11th century); alabaster head, (France, 18th century); terracotta votive feet; brass

47 x 32 x 22 cm

Unique

Headless sandstone bust of St. John the Baptist, (France, late 11th century); alabaster head, (France, 18th century); terracotta votive feet; brass

47 x 32 x 22 cm

Unique

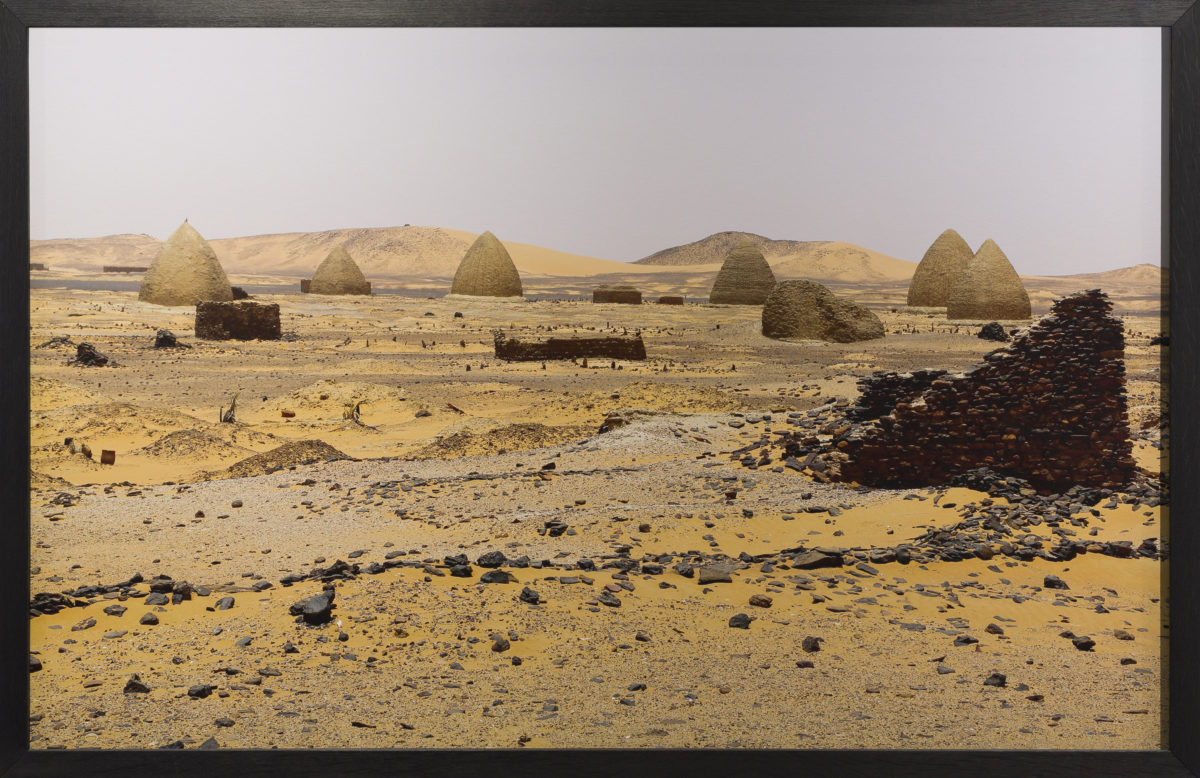

Photograph; 75 x 114,5 x 3 cm

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

Photograph; 75 x 114,5 x 3 cm

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

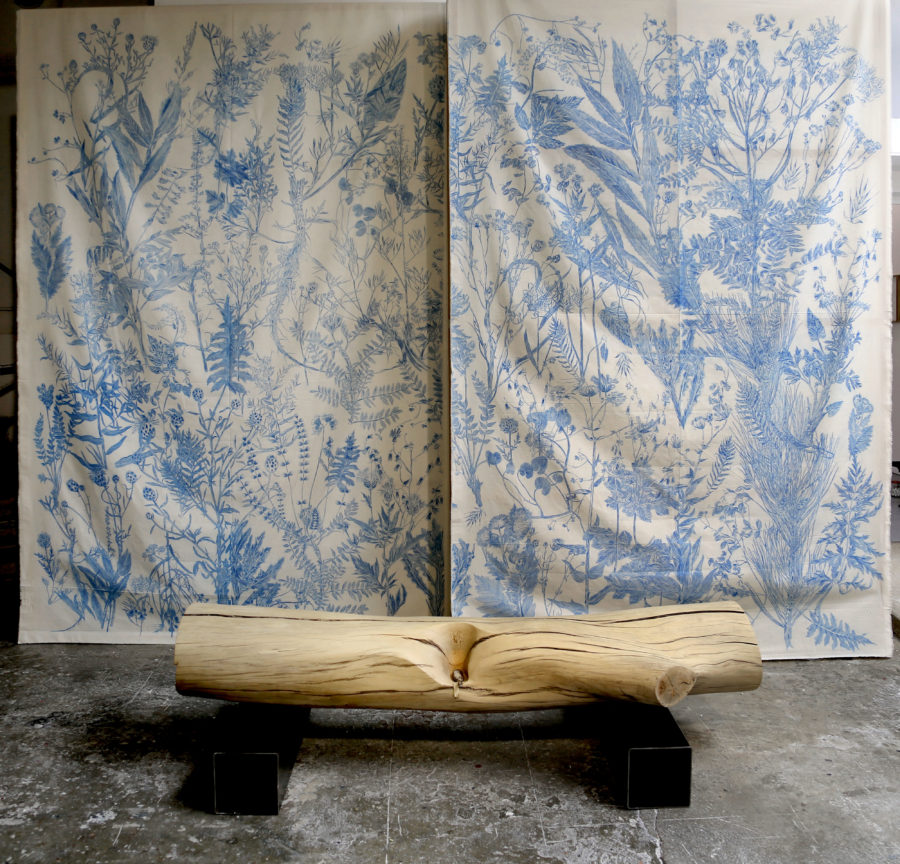

Installation composed of two tree trunks,

animal bones, grafting mastic,

five hand-drawn on canvas,

wooden frames, metal bars, a specimen of

Russian sparrow from a museum cabinet

dating from 1879

Trunk 1 (195 cm long)

Trunk 2 (220 cm high)

Frame (300 cm high)

Installation composed of two tree trunks,

animal bones, grafting mastic,

five hand-drawn on canvas,

wooden frames, metal bars, a specimen of

Russian sparrow from a museum cabinet

dating from 1879

Trunk 1 (195 cm long)

Trunk 2 (220 cm high)

Frame (300 cm high)

Series of 4 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 4 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 3 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 3 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 2 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 2 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

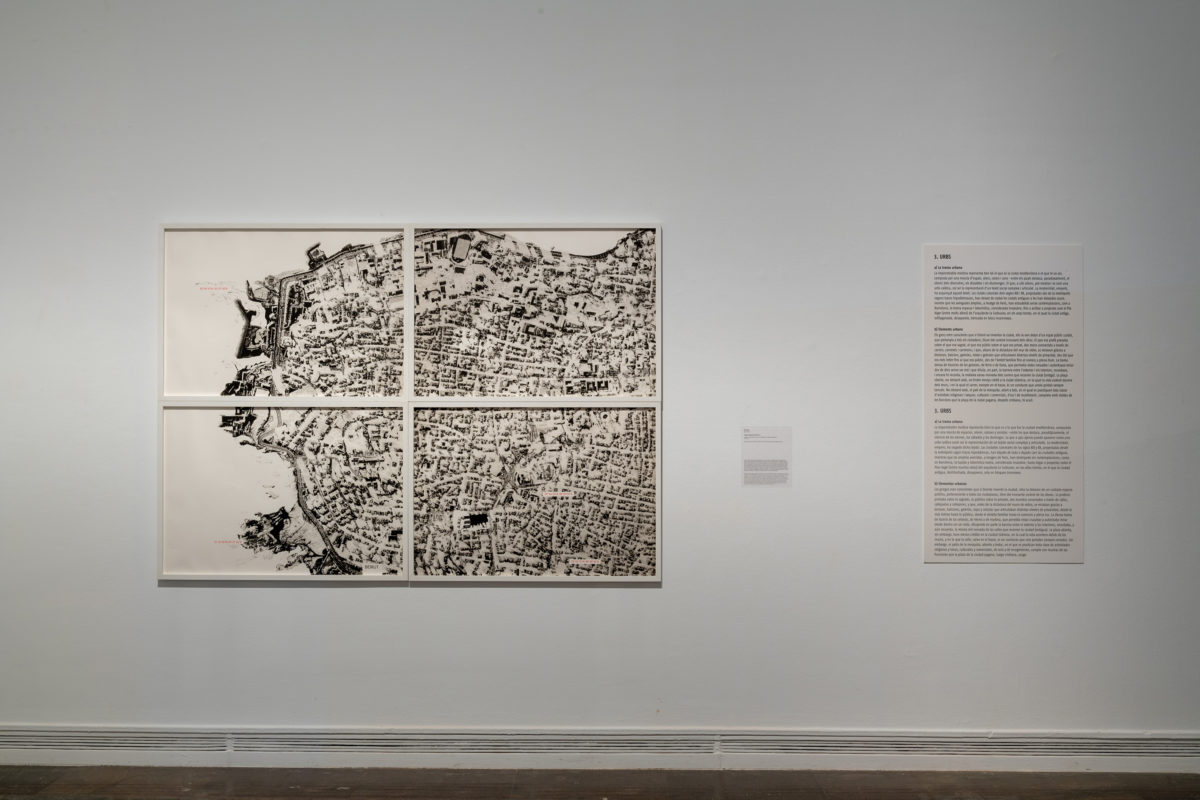

Photographies historiques, vers 1900-1920, charbon, encre ; 52 x 42 x 2.5 cm (chacune)

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Habitar el Mediterráneo, IVAM, 2019

Photographies historiques, vers 1900-1920, charbon, encre ; 52 x 42 x 2.5 cm (chacune)

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Habitar el Mediterráneo, IVAM, 2019

Lightbox, Duratrans print ; 200 x 125 cm x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Installation view: Somniculus, CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, 2017.

Lightbox, Duratrans print ; 200 x 125 cm x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Installation view: Somniculus, CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, 2017.

Wrought iron for rain divination in the shape of snakes (Nigeria, Mumuye people), sarcophagus mask (Egypt, 1st millennium BC), pair of eyes from a limestone sarcophagus (Egypt, Late Period or earlier), concrete

93 x 46 x 30 cm

Unique

Installation of jesmonite ears mounted on a wooden base

220 x 110 x 10 cm

Unique

Acephalous bust in marble from the Roman period, epoxy paste, steel, coating

59 x 29 x 27 cm

Unique

Pair of buffalo horns (Bubalus bubalis, not regulated), wood, instrument strings, steel, concrete

90 x 70 x 46 cm

Unique

Epoxy paste, coating, naturalized throat red, concrete, glass

49,5 x 50 x 35 cm

Unique

Pair of bronze and alabaster sarcophagus eyes from a sarcophagus mask (Egypt, Saite (663-525 BC) or Late Period), brass serving tray, brass

26 x 42 x 33 cm

Unique

installation of 30 eyes (glass, epoxy, coated prosthetic eyes), neon (ContreChamp)

220 x 110 x 10 cm

Unique

Byzantine-period marble head, lower part of face missing, jesmonite, concrete, steel, wood

Unique

Memento mori in sculpted labradorite, patinated bronze, calligraphy on paper

Unique

Patinated bronze

Variable dimensions

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

8 x 11,5 x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

22 x 29 x 35 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

52 x 20 x 10,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1EA

Bronze

23,5 x 16,5 x 7,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

3 x 9 x 3,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

23,5 x 20 x 14,5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Bronze

20 x 16 x 8 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

A series of 8 watercolor and graphite on paper, framed

45,2 x 35,8 x 4 cm (each)

Unique

Watercolor and graphite on paper, framed

45,2 x 35,8 x 4 cm

Unique

Waxed bronze, wood, steel, clay, sand, pigments

168 x 29 x 29

Unique

Steel base, KODAK 35 mm Film and Slide Viewer 6 minutes loop

114 x 33 x 33 cm

Unique

Patinated bronze, steel, clay, sand, wood, epoxy paste, pigments

267 x 181 x 81 cm

Unique

Patinated bronze, steel, clay, sand, wood, plaster, pigments

234 x 77 x 115 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, concrete, plaster, clay, sand, epoxy paste, pigments

76 x 82 x 60 cm

Unique

Marble divinity head from Roman period; steel, plaster

53 x 21 x 11 cm

Unique

bronze, steel

240 x 83 x 74 cm

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Ocular implants made of glass, Wood, Steel, Epoxy Paste, Coating

24 x 30 x 18 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, sand, clay, pigments

42 x 21 x 19 cm

Unique

Terracotta water buffalo from the Han period; wood, steel, brass, plaster, glazed stoneware

42 x 29 x 12 cm

Unique

Steel, sand, clay, pigments

18 x 41 x 21 cm

Unique

Female marble face (17th century); marble draped fragment from Roman period; pair of hand-shaped clappers in the New Kingdom or 3rd Intermediate Period style; steel, wood

77 x 25 x 22 cm

Unique

Pprosthetic glass eyes, wood veneered in walnut bur, golden leaf, brass, resin

25 x 20 x 20 cm

Unique

Idol with pinched nose (Indus Valley); golden leaf, steel, wood, coating

10 x 8 x 8 cm

Unique

Glazed stoneware, concrete, coting

27 x 11 x 11 cm

Unique

Stone head from the 14th/15th century, carved, with flat and smooth eyes to evoke the ancient tradition of depositing a coin in the eyes of a dead man, patinated silver, plaster, steel

49 x 41 x 31 cm

Unique

Egyptian head from an antique sarcophagus, probably Late Empire; steel, wood, coating, sand, pigments, glue

152 x 24 x 50 cm

Unique

Plaster skull, wood, plaster, brass, glue

28 x 18 x 40 cm

Unique

Wood, plaster, brass, glue

23 x 15 x 15 cm

Unique

Ocular prostheses in glass, wood, brass, epoxy paste, coating

21 x 13 x 8,5 cm

Unique

Wood, steel, epoxy paste, coating

33 x 12 x x 12 cm

Unique

HD video, colour, sound, 25’58’’

Paint on fabric, aluminium scaffolding

Resin, pigments, iron, clay

Clay, sand, XPS, wood, pigments, iron

Carved stone, clay, sand, XPS, wood, pigments, iron

Resin, fiberglass, clay, sand, XPS, pigments, iron

Iron-cast mask, wood, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Zoomorphic stone head; iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Animal mask, iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Old wooden mask; iron, xps, clay, sand, pigments / Bull horns, iron, clay, sand, pigments

Unique

Terracotta Nok head (Nigeria, c. 500

B.C.), clay, sand, xps, wood, pigments

88 x 25 x 40 cm

Pink Sandstone of a roaring lion head

sculpture (England, 16th century), clay,

sand, foam, xps, pigments

52 x 105 x 45 cm

Heaume mask Mapico (Tanzania), clay,

sand, xps, wood, pigments

130 x 85 x 67 cm

Gurunsi Monkey Mask, first half of the 20th century, (Burkina Faso), clay sand, xps, pigments

78 x 78 x 78 cm

Unique

Vakono Monkey Mask, first half of the 20th century, (Nigeria), clay sand, xps, pigments

106 x 78 x 48 cm

Unique

Male head with ball headdress (Egypt, Late Period, ca. 664-32 B.C.), clay, sand, pigments, xps, steel

50 x 12 x 8 cm

Unique

Three-channel video installation,

18 min 48 sec (in loop)

Mayan head of a dignitary in orangebeige

terracotta (Mexico or Guatemala,

Classical period, 600-900 AD) , clay, sand,

loam, gesso, pencil, and pigments

160 x 40 x 140 cm

Front part of a Mayan cult vase modeled

after a priest wearing a mouth mask

evoking the Monkey God Hun Batz or Hun

Chouen, terracotta with smoothed orange

engobe (Classical period, 600-900 AD),

clay, sand, loam, gesso, pencil, pigments

198 x 70 x 50 cm

Terracotta Nok head (Nigeria, c. 2100 B.C.),

clay, sand, loam, gesso, pencil, pigments

180 x 75 x 50 cm

Photo © The National Gallery

Photo © The National Gallery

Photo © The National Gallery

Photo © The National Gallery

Photo © The National Gallery

Amulet of the Egyptian falcon god Horus in glass paste (Ancient Egypt, Late Period), glazed stoneware, 17,5 x 13,5 x 7,8 cm

Terracotta statuette head representing a veiled woman (Hellenistic period, Cyprus), small animal head in green stone (Pre-Columbian America), glazed stoneware, wood, 24,5 x 23 x 12,5 cm

Beads, cylindrical face in glass paste (Phoenicia, 1st millennium B.C.), coral branch, glazed stoneware, 23 x 12,7 x 19,5 cm

19th century torso of Apollo in marble, beads decorated with eyes in glass paste (Ancient period, Mediterranean basin), glazed stoneware, 50 x 31 x 20,5 cm

Carved wooden mask with remains of polychromy (Late Period, 7th – 4th century B.C.), glazed stoneware, 50 x 28 x 21 cm

Pair of ocular protheses in glass, moulding in glazed stoneware, 15 x 16 x 21 cm

Fragment of a 19th century white Roman marble sculpture with legs and feet (human size); antique Egyptian bronze eyes with matching eyebrows, remains of azurite and inlays; feathered headdress from Angola (Tchokwe culture); glazed stoneware and metal, 130 x 63 x 51 cm

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed)

Diptych, watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

Diptych, watercolor and graphite on paper, 41,5 x 50 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

Twelve drawings, watercolor and graphite on paper, 50 x 41,5 x 3,5 cm (framed, each)

19th century patented bronze Sphinx, taxidermy bird, red colorant, 40 x 100 x 40 cm

Taxidermy porcupine fish, 20th century, pole from Salampasu village, anthropomorphic wooden head, metal rod, wood and neoprene tube, 160 x 60 x 50 cm

19th century wooden pole leg, taxidermy Falco Subbuteo, Chinese dragon head in porcelain, metal rod and wood, 60 x 40 x 40 cm

Osteological Ceratogymna atrata, Salampasu head mask from Central Africa, wooden base, 100 x 40 x 40 cm

Lightbox, Duratrans print ; 200 x 125 x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 1 AP

Tête d’Eros, marbre; figurine de protection Lobi du Burkina Faso enois; aile de geai séchée ; 50 x 15 x 15 cm

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Jameel Art Center, Dubai, 2019.

Terracotta statue representing a sphinx, Nok Civilization, 500 BC approx., head of a roe deer in taxidermy, 1950

Tête en marbre, 18e siècle, bois, ficelle, trépied en métal ; 130 x 40 x 40 cm

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Jameel Art Center, Dubai, 2019.

Headless sandstone bust of St. John the Baptist, (France, late 11th century); alabaster head, (France, 18th century); terracotta votive feet; brass

47 x 32 x 22 cm

Unique

Photograph; 75 x 114,5 x 3 cm

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

Installation composed of two tree trunks,

animal bones, grafting mastic,

five hand-drawn on canvas,

wooden frames, metal bars, a specimen of

Russian sparrow from a museum cabinet

dating from 1879

Trunk 1 (195 cm long)

Trunk 2 (220 cm high)

Frame (300 cm high)

Series of 4 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 3 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Series of 2 lithographs ; 105 x 74,5 x 3,5 cm (each)

Edition of 5

Photographies historiques, vers 1900-1920, charbon, encre ; 52 x 42 x 2.5 cm (chacune)

Œuvre unique

Vue d’installation : Habitar el Mediterráneo, IVAM, 2019

Lightbox, Duratrans print ; 200 x 125 cm x 5 cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Installation view: Somniculus, CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, 2017.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf after Poussin, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a bas-relief pedestal in jesmonite, wood and gold leaf, and an eight-legged two-headed taxidermy lamb.

188 x 137,5 x 63,5 cm (display case) | 100 x 45 x 50 cm (bas-relief pedestal) | 43 x 44 x 32 cm (taxidermy lamb)

Unique

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’) after Leonardo, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a cardbaord rendition of a bullet damage, newspapers, a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, a sculpture comprised of glass eyes and a metal stand.

220 x 170 x 70 cm (display case) | 70 x 7 cm (cardboard)

Unique

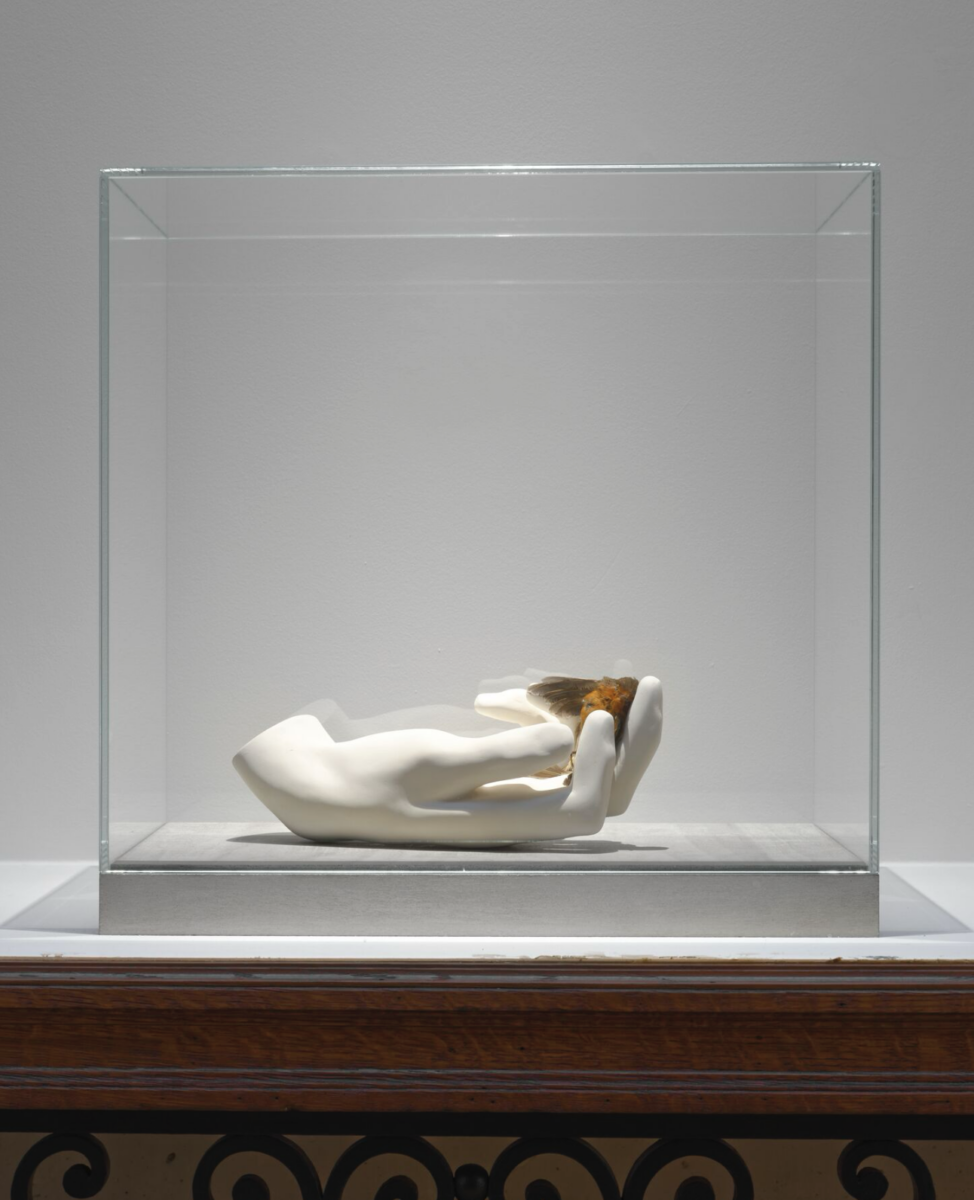

The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’) after Vélazquez, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a 19th-century head carving in marble, a wooden reclining Venus sculpture, a mirror and red velvet fabric.

200 x 220 x 80 cm (display case) | 40 x 30 x 30 cm (marble head) | 170 x 80 x 80 cm (wooden Venus)

Unique

Self Portrait at the Age of 63 after Rembrandt, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing the sculpture of Rembrandt’s head in wax and a metal frame.

166,4 x 127 x 53,3 cm (display case)

Unique

The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’) after Baroccio, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a taxidermy goldfinch and a porcelain hand.

147,5 x 81,2 x 40,5 cm (display case) | 12 x 10 x 7 cm (goldfinch) | 12 x 37 x 37 cm (porcelain hand)

Unique

Photos © The National Gallery, London, 2022

Ali Cherri presents work that considers how histories of trauma can be explored through a response to museum and gallery collections. This exhibition, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ introduces cabinets of curiosity into the heart of the Sainsbury Wing, containing assembled fragments that might look like relics from another collection.

Starting with research in the National Gallery’s archive, Cherri uncovered accounts of five paintings that were vandalised while on display. He was struck by the public’s highly emotional response to these attacks, finding that newspaper articles would describe the damages as if they were wounds inflicted on a living being – even referring to the Gallery’s conservators as surgeons. He also noticed an overwhelming urge to ‘heal’, make good and hide the damage. This personification of artworks, and the suggestion that they can experience distress, is reflected in the exhibition’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play ‘The Merchant of Venice’. In response, Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations that recall aspects of each painting and that imagine its life following the vandalism. They bring into question what Cherri calls the ‘politics of visibility’; the decisions we make about how, and to what extent, we accept trauma within museums. By translating each damaged work into a series of strange objects, Cherri reminds us that we are never truly the same after experiencing violence. Assembled in five old-fashioned vitrines reminiscent of early museum displays and cabinets of curiosity, lined up in the Sainsbury Wing and surrounded by Renaissance paintings that often show wounds and suffering, Cherri’s installations resonate with sympathy.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf after Poussin, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a bas-relief pedestal in jesmonite, wood and gold leaf, and an eight-legged two-headed taxidermy lamb.

188 x 137,5 x 63,5 cm (display case) | 100 x 45 x 50 cm (bas-relief pedestal) | 43 x 44 x 32 cm (taxidermy lamb)

Unique

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’) after Leonardo, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a cardbaord rendition of a bullet damage, newspapers, a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, a sculpture comprised of glass eyes and a metal stand.

220 x 170 x 70 cm (display case) | 70 x 7 cm (cardboard)

Unique

The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’) after Vélazquez, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a 19th-century head carving in marble, a wooden reclining Venus sculpture, a mirror and red velvet fabric.

200 x 220 x 80 cm (display case) | 40 x 30 x 30 cm (marble head) | 170 x 80 x 80 cm (wooden Venus)

Unique

Self Portrait at the Age of 63 after Rembrandt, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing the sculpture of Rembrandt’s head in wax and a metal frame.

166,4 x 127 x 53,3 cm (display case)

Unique

The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’) after Baroccio, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a taxidermy goldfinch and a porcelain hand.

147,5 x 81,2 x 40,5 cm (display case) | 12 x 10 x 7 cm (goldfinch) | 12 x 37 x 37 cm (porcelain hand)

Unique

Photos © The National Gallery, London, 2022

Ali Cherri presents work that considers how histories of trauma can be explored through a response to museum and gallery collections. This exhibition, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ introduces cabinets of curiosity into the heart of the Sainsbury Wing, containing assembled fragments that might look like relics from another collection.

Starting with research in the National Gallery’s archive, Cherri uncovered accounts of five paintings that were vandalised while on display. He was struck by the public’s highly emotional response to these attacks, finding that newspaper articles would describe the damages as if they were wounds inflicted on a living being – even referring to the Gallery’s conservators as surgeons. He also noticed an overwhelming urge to ‘heal’, make good and hide the damage. This personification of artworks, and the suggestion that they can experience distress, is reflected in the exhibition’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play ‘The Merchant of Venice’. In response, Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations that recall aspects of each painting and that imagine its life following the vandalism. They bring into question what Cherri calls the ‘politics of visibility’; the decisions we make about how, and to what extent, we accept trauma within museums. By translating each damaged work into a series of strange objects, Cherri reminds us that we are never truly the same after experiencing violence. Assembled in five old-fashioned vitrines reminiscent of early museum displays and cabinets of curiosity, lined up in the Sainsbury Wing and surrounded by Renaissance paintings that often show wounds and suffering, Cherri’s installations resonate with sympathy.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf after Poussin, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a bas-relief pedestal in jesmonite, wood and gold leaf, and an eight-legged two-headed taxidermy lamb.

188 x 137,5 x 63,5 cm (display case) | 100 x 45 x 50 cm (bas-relief pedestal) | 43 x 44 x 32 cm (taxidermy lamb)

Unique

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’) after Leonardo, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a cardbaord rendition of a bullet damage, newspapers, a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, a sculpture comprised of glass eyes and a metal stand.

220 x 170 x 70 cm (display case) | 70 x 7 cm (cardboard)

Unique

The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’) after Vélazquez, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a 19th-century head carving in marble, a wooden reclining Venus sculpture, a mirror and red velvet fabric.

200 x 220 x 80 cm (display case) | 40 x 30 x 30 cm (marble head) | 170 x 80 x 80 cm (wooden Venus)

Unique

Self Portrait at the Age of 63 after Rembrandt, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing the sculpture of Rembrandt’s head in wax and a metal frame.

166,4 x 127 x 53,3 cm (display case)

Unique

The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’) after Baroccio, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a taxidermy goldfinch and a porcelain hand.

147,5 x 81,2 x 40,5 cm (display case) | 12 x 10 x 7 cm (goldfinch) | 12 x 37 x 37 cm (porcelain hand)

Unique

Photos © The National Gallery, London, 2022

Ali Cherri presents work that considers how histories of trauma can be explored through a response to museum and gallery collections. This exhibition, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ introduces cabinets of curiosity into the heart of the Sainsbury Wing, containing assembled fragments that might look like relics from another collection.

Starting with research in the National Gallery’s archive, Cherri uncovered accounts of five paintings that were vandalised while on display. He was struck by the public’s highly emotional response to these attacks, finding that newspaper articles would describe the damages as if they were wounds inflicted on a living being – even referring to the Gallery’s conservators as surgeons. He also noticed an overwhelming urge to ‘heal’, make good and hide the damage. This personification of artworks, and the suggestion that they can experience distress, is reflected in the exhibition’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play ‘The Merchant of Venice’. In response, Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations that recall aspects of each painting and that imagine its life following the vandalism. They bring into question what Cherri calls the ‘politics of visibility’; the decisions we make about how, and to what extent, we accept trauma within museums. By translating each damaged work into a series of strange objects, Cherri reminds us that we are never truly the same after experiencing violence. Assembled in five old-fashioned vitrines reminiscent of early museum displays and cabinets of curiosity, lined up in the Sainsbury Wing and surrounded by Renaissance paintings that often show wounds and suffering, Cherri’s installations resonate with sympathy.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf after Poussin, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a bas-relief pedestal in jesmonite, wood and gold leaf, and an eight-legged two-headed taxidermy lamb.

188 x 137,5 x 63,5 cm (display case) | 100 x 45 x 50 cm (bas-relief pedestal) | 43 x 44 x 32 cm (taxidermy lamb)

Unique

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’) after Leonardo, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a cardbaord rendition of a bullet damage, newspapers, a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, a sculpture comprised of glass eyes and a metal stand.

220 x 170 x 70 cm (display case) | 70 x 7 cm (cardboard)

Unique

The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’) after Vélazquez, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a 19th-century head carving in marble, a wooden reclining Venus sculpture, a mirror and red velvet fabric.

200 x 220 x 80 cm (display case) | 40 x 30 x 30 cm (marble head) | 170 x 80 x 80 cm (wooden Venus)

Unique

Self Portrait at the Age of 63 after Rembrandt, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing the sculpture of Rembrandt’s head in wax and a metal frame.

166,4 x 127 x 53,3 cm (display case)

Unique

The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’) after Baroccio, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a taxidermy goldfinch and a porcelain hand.

147,5 x 81,2 x 40,5 cm (display case) | 12 x 10 x 7 cm (goldfinch) | 12 x 37 x 37 cm (porcelain hand)

Unique

Photos © The National Gallery, London, 2022

Ali Cherri presents work that considers how histories of trauma can be explored through a response to museum and gallery collections. This exhibition, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ introduces cabinets of curiosity into the heart of the Sainsbury Wing, containing assembled fragments that might look like relics from another collection.

Starting with research in the National Gallery’s archive, Cherri uncovered accounts of five paintings that were vandalised while on display. He was struck by the public’s highly emotional response to these attacks, finding that newspaper articles would describe the damages as if they were wounds inflicted on a living being – even referring to the Gallery’s conservators as surgeons. He also noticed an overwhelming urge to ‘heal’, make good and hide the damage. This personification of artworks, and the suggestion that they can experience distress, is reflected in the exhibition’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play ‘The Merchant of Venice’. In response, Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations that recall aspects of each painting and that imagine its life following the vandalism. They bring into question what Cherri calls the ‘politics of visibility’; the decisions we make about how, and to what extent, we accept trauma within museums. By translating each damaged work into a series of strange objects, Cherri reminds us that we are never truly the same after experiencing violence. Assembled in five old-fashioned vitrines reminiscent of early museum displays and cabinets of curiosity, lined up in the Sainsbury Wing and surrounded by Renaissance paintings that often show wounds and suffering, Cherri’s installations resonate with sympathy.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf after Poussin, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a bas-relief pedestal in jesmonite, wood and gold leaf, and an eight-legged two-headed taxidermy lamb.

188 x 137,5 x 63,5 cm (display case) | 100 x 45 x 50 cm (bas-relief pedestal) | 43 x 44 x 32 cm (taxidermy lamb)

Unique

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’) after Leonardo, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a cardbaord rendition of a bullet damage, newspapers, a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, a sculpture comprised of glass eyes and a metal stand.

220 x 170 x 70 cm (display case) | 70 x 7 cm (cardboard)

Unique

The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’) after Vélazquez, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a 19th-century head carving in marble, a wooden reclining Venus sculpture, a mirror and red velvet fabric.

200 x 220 x 80 cm (display case) | 40 x 30 x 30 cm (marble head) | 170 x 80 x 80 cm (wooden Venus)

Unique

Self Portrait at the Age of 63 after Rembrandt, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing the sculpture of Rembrandt’s head in wax and a metal frame.

166,4 x 127 x 53,3 cm (display case)

Unique

The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’) after Baroccio, 2022

Installation comprised of a display case containing a taxidermy goldfinch and a porcelain hand.

147,5 x 81,2 x 40,5 cm (display case) | 12 x 10 x 7 cm (goldfinch) | 12 x 37 x 37 cm (porcelain hand)

Unique

Photos © The National Gallery, London, 2022

Ali Cherri presents work that considers how histories of trauma can be explored through a response to museum and gallery collections. This exhibition, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ introduces cabinets of curiosity into the heart of the Sainsbury Wing, containing assembled fragments that might look like relics from another collection.

Starting with research in the National Gallery’s archive, Cherri uncovered accounts of five paintings that were vandalised while on display. He was struck by the public’s highly emotional response to these attacks, finding that newspaper articles would describe the damages as if they were wounds inflicted on a living being – even referring to the Gallery’s conservators as surgeons. He also noticed an overwhelming urge to ‘heal’, make good and hide the damage. This personification of artworks, and the suggestion that they can experience distress, is reflected in the exhibition’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play ‘The Merchant of Venice’. In response, Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations that recall aspects of each painting and that imagine its life following the vandalism. They bring into question what Cherri calls the ‘politics of visibility’; the decisions we make about how, and to what extent, we accept trauma within museums. By translating each damaged work into a series of strange objects, Cherri reminds us that we are never truly the same after experiencing violence. Assembled in five old-fashioned vitrines reminiscent of early museum displays and cabinets of curiosity, lined up in the Sainsbury Wing and surrounded by Renaissance paintings that often show wounds and suffering, Cherri’s installations resonate with sympathy.

The Gatekeepers, 2020

Wooden poles, metal, taxidermy, woodcarving, various objects

Totem 1: Fire

Sheep skin, 20th century mask assigned to the Bushong ethnic group in Zaire made in light tropical wood, darkly framed, for use in initiation ceremonies, characterized by its protruding eyes and serrated pattern on the forehead, burlap hood, decorated with feathers and cowrie shells, bast beard, Krahn mask with a fantastic beast’s head, Ivory Coast, second half of the 20th century, ostrich feathers, neoprene tube, paint.

Totem 2: Earth

Boar mask from Melanesia, 1st half of the 20th century: brown softwood, three-dimensional representation of a small boar’s head with two tusks inserted, weathered, strong, inactive termite infestation, Taxidermy Phacochoerus aethiopicus, Sylvicapra grimmia grimmia, and Raphicerus campestri, with the taxidermist’s stamp on the reverse: ‘Nico van Rooyen Taxidermy’; natural hair, paint.

Totem 3: Wind

Melanesian mask probably from the Sepik region, 1st half of the 20th century: hardwood with remains of old paint, presumably ancestral mask, eyes made from cowrie shells, real hair; mask depicting a face causing fear, Guéré people, Ivory Coast, ca. 1960: wood, fibers, textiles, iron, hair and other materials, aluminium rod, paint.

Totem 4: Water

Grotesque mask in metal, ca. 1970, taxidermy fish, plastic tubes, paint.

Commissioned by Manifesta 13 Marseille, supported by [N.AI] Project, Ammodo and Drosos Foundation

Photos © Jean Christophe Lett / Manifesta et © Ali Cherri

The Gatekeepers draws on the tradition of erecting totem poles at the gates of certain communities. These vertical pillars can welcome, warn or simply tell the story of the people who once lived there. Using figures inspired by the animal kingdom, the aquatic world or crossbreed beasts, The Gatekeepers welcome visitors to the Musee des Beaux-Arts de Marseille and offer a tribute to the souls of all the animals lodged in the Museum d’Histoire naturelle, only a few steps away, in the opposite wing of Palais Longchamp. Despite the proximity of both these institutions, they reassert the divide between nature and culture – a key feature of knowledge production in western modernity. These vertical pillars offer a substitute to the “pillars of knowledge” that these museums represent, while also echoing the colonnade balcony that connects them both.

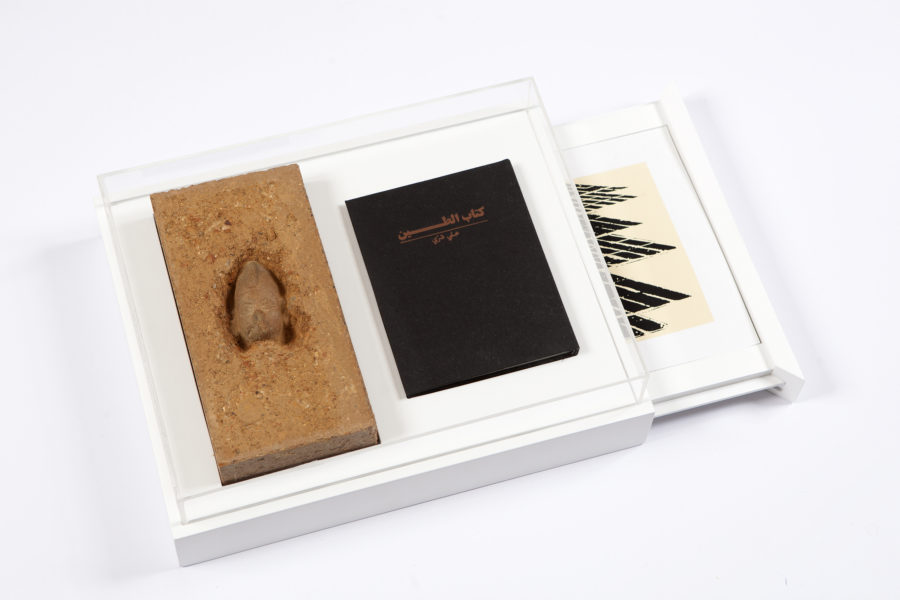

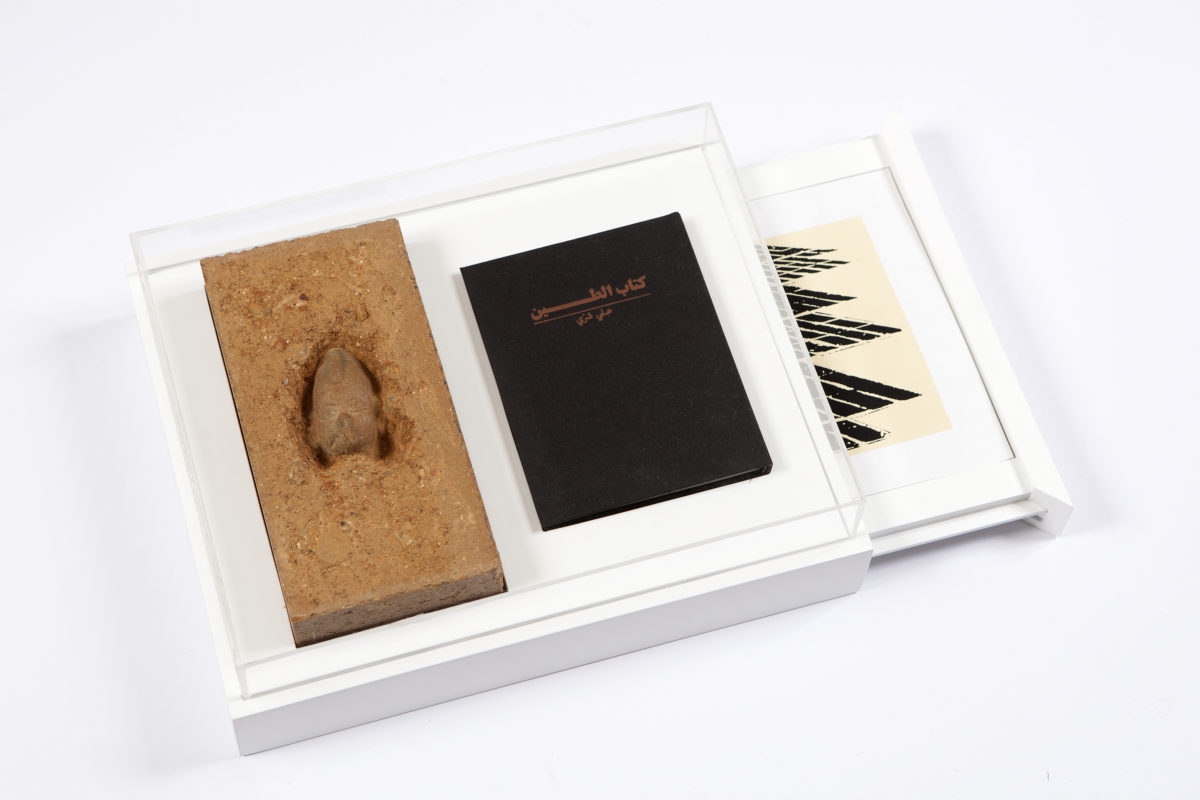

The Book of Mud, 2018-2020

Published by Dongola Limited Editions

Vision and Direction: Abed Alkadiri

Edition of 65

The Book

Limited Edition of 65

Story by Ali Cherri

English Text | Lina Mounzer

Arabic Text | Mariam Janjelo

Design | Reza Abedini

Assistant Designer | Lama Barakat

Photography | Kassem Dabaji

Printing and Binding | Riad Youssef

Cover | Black fabric, Foil debossing

Inside pages | Offset printing on Freelife Vellum (140 gsm)

Binding | Double bound hardback

Printed in Beirut, Lebanon

The Mudbrick

Unique piece, 2019 | Artifact from the artist’s collection nested in handmade, sun-dried mudbrick

Made in Deux-Sèvres, France | Frantz Lavenu

The Print

Brickyard, 2020

Silkscreen printed in two colors on Oikos extra white (100 gsm) signed and numbered by the artist

Edition of 65

Printed in Beirut by Salim Samara

The Box

Carved beech massif, plywood, and MDF painted white host the book and brick with a pullout drawer and a plexiglass lid

Box Production | Tanya Elhajj

The Book of Mud is a manifesto, a reverie, a story of earth and water. From floods and deluges to droughts and water scarcity, mud is the materialisation of the aquatic reality of our world. Neither land nor water, yet also both, mud embodies an in-between state—a rich space for imagination.

Ali Cherri, the Paris-based Lebanese multidisciplinary artist, conceives The Book of Mud as an exploration of the past and the ways in which it inscribes itself physically: eroding, shaping, reforming, becoming itself through upheaval and destruction. In this project, Cherri is a storyteller in conversation with writers in both English and Arabic. Together they unveil the story of the mud – “… a story of perpetually shifting geographies, of elemental forces and terrain that cracks and rumbles and breaks over eons into new topographical formations. If mud had its own memory, what might it deem worth remembering?”

In this book of memory, Cherri understands mud as the vessel and the water within, as the brick that roots us to place and home, and the river that carries us to exploration elsewhere. Deeply embedded in narratives of creation, mud grounds life in a cycle that always finds its way back into the earth.

Artefacts, collected and encased in mudbrick, accompany the book to symbolise this timeless process. Worldly values embodied by these objects are once again ‘grounded,’ returned to the earth from which they came. A silkscreen print visualises a field of mudbricks drying in the sun, uniting earth and water as the building blocks of civilization. This art object, the culmination of a two-year project, features books, silkscreen, and mudbrick enclosed in a handcrafted white wooden box.

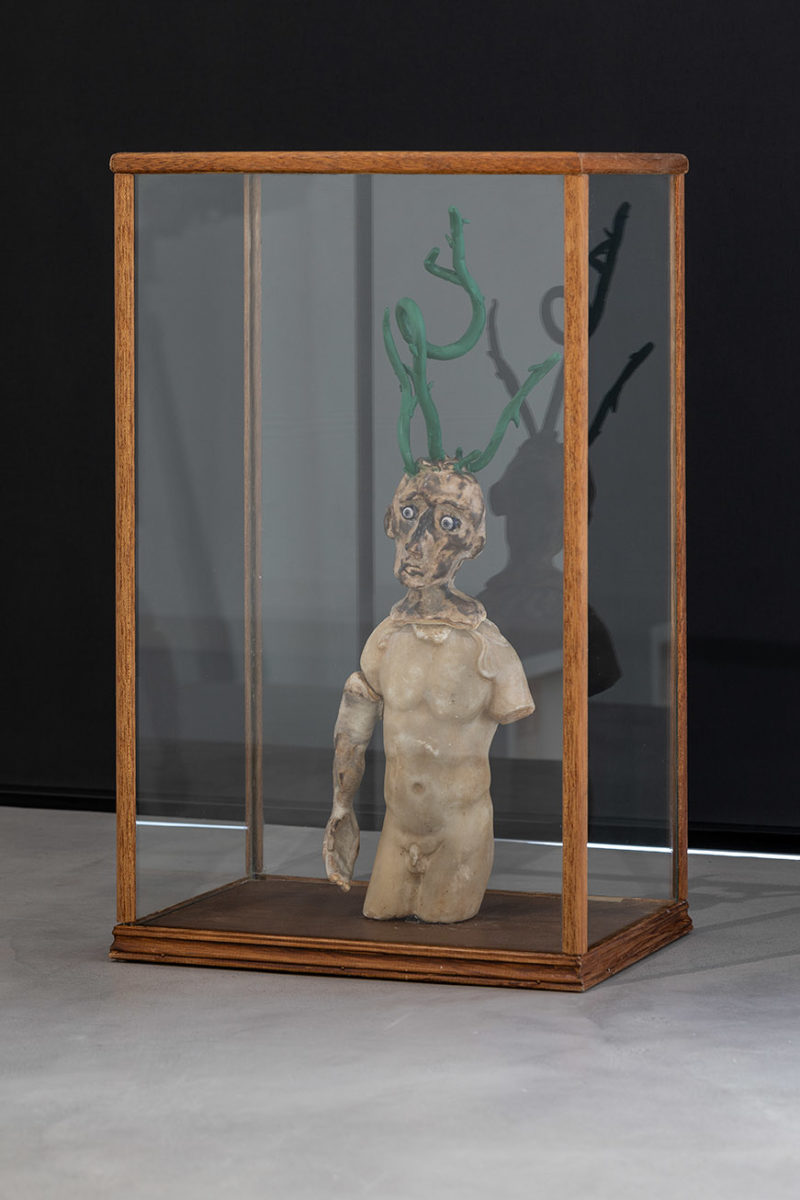

Graftings (A) – (J), 2018-2019

Variable dimensions

Unique

In agricultural botany, a graft is a sprout inserted into a slit on a trunk or stem of a living plant, from which it receives sap. In medicine, it’s a piece of living tissue that is transplanted surgically to replace diseased or injured tissue. Grafting is often used to create new varieties or species, and it can sometimes be made between different species, that is, human and animal.

By performing the assemblage of fragile things, a new appearance, a new life is granted.

These hybrids give us a glimpse into the power of matter. By looking at the life cycles of objects and the complexity of preservation and repre-sentation of matter, the relationships and tensions between the organic and synthetic, figurative and the abstract, the found and made object are revealed.

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G),

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (A)

Grafting (A)

Grafting (B)

Grafting (D)

Graftings (A) – (J), 2018-2019

Variable dimensions

Unique

In agricultural botany, a graft is a sprout inserted into a slit on a trunk or stem of a living plant, from which it receives sap. In medicine, it’s a piece of living tissue that is transplanted surgically to replace diseased or injured tissue. Grafting is often used to create new varieties or species, and it can sometimes be made between different species, that is, human and animal.

By performing the assemblage of fragile things, a new appearance, a new life is granted.

These hybrids give us a glimpse into the power of matter. By looking at the life cycles of objects and the complexity of preservation and repre-sentation of matter, the relationships and tensions between the organic and synthetic, figurative and the abstract, the found and made object are revealed.

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G),

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (A)

Grafting (A)

Grafting (B)

Grafting (D)

Graftings (A) – (J), 2018-2019

Variable dimensions

Unique

In agricultural botany, a graft is a sprout inserted into a slit on a trunk or stem of a living plant, from which it receives sap. In medicine, it’s a piece of living tissue that is transplanted surgically to replace diseased or injured tissue. Grafting is often used to create new varieties or species, and it can sometimes be made between different species, that is, human and animal.

By performing the assemblage of fragile things, a new appearance, a new life is granted.

These hybrids give us a glimpse into the power of matter. By looking at the life cycles of objects and the complexity of preservation and repre-sentation of matter, the relationships and tensions between the organic and synthetic, figurative and the abstract, the found and made object are revealed.

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G),

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (A)

Grafting (A)

Grafting (B)

Grafting (D)

Graftings (A) – (J), 2018-2019

Variable dimensions

Unique

In agricultural botany, a graft is a sprout inserted into a slit on a trunk or stem of a living plant, from which it receives sap. In medicine, it’s a piece of living tissue that is transplanted surgically to replace diseased or injured tissue. Grafting is often used to create new varieties or species, and it can sometimes be made between different species, that is, human and animal.

By performing the assemblage of fragile things, a new appearance, a new life is granted.

These hybrids give us a glimpse into the power of matter. By looking at the life cycles of objects and the complexity of preservation and repre-sentation of matter, the relationships and tensions between the organic and synthetic, figurative and the abstract, the found and made object are revealed.

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G),

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (H), Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (I)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (G), Grafting (H)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (C)

Exhibition view: Phantom Limb, Jameel Arts Centre, 2019

Grafting (A)

Grafting (A)

Grafting (B)

Grafting (D)

The Breathless Forest, 2019

Mixed-media in situ installation

Variable dimensions

Installation views: La Vitrine, Beirut Art Residency, Beirut, 2019

The Breathless Forest takes the form of a failed diorama, a three dimensional, life-size, simulated environment in which nature is put on display. By failing to immerse the viewer entirely in the illusion, The Breathless Forest explores “nature” as a construct embedded in the cultural, symbolic, and political orders of human history. Located on a busy street of Beirut, the installation offers a window through which the pedestrians can “peek into a dead forest”. While dioramas offer ways to produce permanence, to stop decomposition and keep things from disappearing, in The Breathless Forest decay seem to have already taken place. In spite of the death, the skinning and the dismemberment of the taxidermy animals composing the diorama, their glass eyes succeed in returning our gazing.

The Tower of Mud, 2019

Installation médium mixtes

Dimensions variables,

Unique

Eternity and a Day, 2019

Video

La fascination pour la boue à la fois comme matière et métaphore possède une riche histoire. Sa transformation en matériau de construction est un processus aussi vieux que l’humanité. La fabrication artisanale de brique est pratiqué depuis des millénaires et utilise tous les éléments naturels: terre, eau, feu et air. L’histoire de la boue est celle de géographies en perpétuel changement, de forces élémentaires et de terrains qui se craquellent en nouvelles formations topographiques. Les premiers dieux que l’Homme a imaginé ont fait le monde à partir de boue. De la boue, l’Homme fabrique la poterie et les premiers récipients pour conserver et transporter. La boue est aussi devenue mémoire: elle contient et conserve. La première forme de vie est venue de la boue. L’endroit où la terre et l’eau se rencontrent et se mélangent a donné naissance aux premiers organismes unicellulaires à l’origine de toutes les créatures vivantes et respirantes du monde: la flore, la faune et les champignons. Dans The Tower of Mud (2019), les briques s’érigent pour former une structure verticale, une tour qui émerge d’une tradition aussi vieille que nos souvenirs du temps. Suivant le symbolisme constant et évolutif de l’aspiration à la verticalité, The Tower of Mud est un monument commémoratif à l’union du sol et de l’eau. On dit qu’une poignée de boue contient «plus d’informations organisées que la surface de toutes les autres planètes connues». Si la boue avait sa propre mémoire, de quoi pourrait-elle se souvenir?

Avec une profonde conscience historique, la pratique d’Ali Cherri retrace les correspondances politiques et géologiques pour étudier les effets de la catastrophe, à la fois anthropique et géologique. Dans l’épopée de Gilgamesh de Mésopotamie, Gilgamesh, roi d’Uruk (datant de la troisième dynastie d’Ur, vers 2100 avant J.-C.), «appelé dieu et homme», se lance dans une quête de la vie éternelle après avoir vu son ami Enkidu mourrir sous ses yeux. La mort d’Enkidu, qui était fait d’argile et d’eau, confronta Gilgamesh à sa propre mortalité, qu’il n’avait jamais craint jusque là. En examinant différents mythes de la création, Eternity and a Day (2019), créée la biennale biennale, navigue dans des histoires de créatures de boue, comme Enkidu, et de marais, dans lesquels on peut se noyer mais aussi renaître. Très peu d’espaces représentent la périphérie de l’existence humaine aussi bien que les marécages boueux. Les eaux stagnantes au-dessus desquelles volent des insectes bourdonnants et dans lesquelles nages des créatures de toutes sortes, dévoilent le tableau complexe d’une désolation sourde et sombre, à la fois inquiétante et envahissante. Ni complètement sol ni complètement eau, ce terrain entre deux est craint, énigmatique et fantomatique, provoquant mort et maladie. Les sites de collecte de boue sont également des marais géopolitiques littéraux où les forces économiques convergent: des carrières de briques traditionnelles aux marécages de boue des chasseurs d’or.

Plot for a Possible Resurrection, 2018

Installation comprises mud bricks, a statue of Jesus Christ Resurrection in stone for the 15th century, a wooden statue of Jesus Christ, with a damaged face from the 15th century, water

Variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: biennale internationale d’art contemporain de Melle, Le Grand Monnayage. Photo © Origins Studio

The placement of the archaeological object is central in the work of Ali Cherri. It raises questions about the choice of objects shown in museums because it is not trivial and indicates the vision that each culture wishes to give to its history, what trace we preserve from the past.

With Plot for a Possible Resurrection, Ali Cherri creates a space of archaeological excavations where objects are revealed showing traces of erosion. Mud serves to cultivate crops for its richness, but also engulfs everything during cataclysms. It is this mud that occupies the exhibition space and exposes some objects that it has imprisoned within. Nature always takes over and therefore, the objects transformed by man erode. The cut stone becomes stone again, the soil becomes mud again.

Although the silver mines of Melle had been forgotten for several centuries, then were rediscovered, Ali Cherri was interested in the formation of layers of limestone and stalactites that the penetration of water formed on the stone rubble left by the miners. These natural marks of the passage of time and of the victory of nature over human interventions were sources of inspiration for the work Plot for a Possible Resurrection that becomes part of this biennial as a mirror of the mines.

Somniculus, 2017

HD video, colour, sound

14 min 40 sec

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

Edition 1/5: Musée national d’art moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou

Coproduction: Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques and CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux.

Filmed inside a series of empty museum galleries across Paris, Cherri’s new work Somniculus (the Latin word for “light sleep”) articulates the tension between the lives of dead objects and the living world that surrounds them. Artefacts from museums of ethnography, archaeology and natural sciences are all presented in their existing cultural context as the surviving objects of human interest. Preserved inside this structure of historiographic display, each object is representative of a place or a time and each artefact lives on as a container of its own history. What if we suspended these objects outside this constructed framework of controlled meaning? Would their ideological value become any less tangible?

As a result of periods of Enlightenment, imperialism and colonial expansion over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, museums in Paris became some of the world’s most encyclopaedic institutions. The trajectory of the modern museum, from the cabinet of curiosities to a nationalist project to the colonial institution, and on to the neoliberal structure of the present day, reflects the shifting ideologies of our civilization. In Somniculus, the viewer is presented with a series of windows through which the objects in the museum escape these ideological regimes altogether. We see how these objects might relate to us in a pre-modern sense, as objects endowed with their own autonomy and agency.

Although the modern era has given rise to a divide between the living and the non-living, human and nonhuman, culture and nature, the project of existing museum practice seeks to bring objects of the past to life by reactivating historical narratives. Forming a discontinuity, the mummified bodies from ancient Egypt, taxidermy wildlife and fragments of non-European cultures found in Somniculus seem less than alive, yet they speak to us and haunt us still, as if to transcend their contained existence. The objects no longer represent a coherent representational universe, defined by ordering and classification, but rather the beginning of another fiction.

Though it would seem that the modern museum is a space of the object rather than the subject, the human body has played an integral role in the construction of our world as we know it. While the evolution of man is often defined by anthropological and anatomical developments in science, our physical relationship to objects in museums is often one of passive detachment. We are reminded that the idea of looking is not a political act of questioning the reality before us, but a way of probing the origin of the gaze itself. A camera lingers over torch-lit objects whose eyes shine back at us, while other objects lack the ability to see altogether – their view is that of an abyss or a black hole. Is it the lack of sight that prevents them from seeing, or the absence of eyes?

The apparent necessity of seeing, the act of closing and opening the eyes, recalls the inevitability of sleep and its inescapable shadow: death. Shining a light on these spaces of perpetual significance within Western culture, Somniculus brings a heightened awareness to the act of looking and seeing in the museum. As an anonymous man sleeps in an otherwise empty gallery we realise that he too is representative of a culture, a time, a place. These fragments of loss, destruction and violence stand in as representations of civilizations’ past. In accordance with the cultures they serve to represent, these objects are neither caught inside the deep dark past nor immediately visible in the light of our present day, but forever waiting to be awakened.

— Osei Bonsu

Where do birds go to hide (I), 2017

Installation comprises a tree trunk, animal bones, grafting mastic, hand-drawn canvas and wood

Variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: Biennale de Lyon 2017. Photo © Blaise Adilon

Where do birds go to hide (II), 2017

Installation comprises a tree trunk and a Russian specimen of a sparrow from a museum cabinet dated from 1879, metallic bars and hand-drawn canvas

Variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: Dénaturé, Galerie Imane Farès, 2017-2018; MAC International, MAC, Belfast, 2017. Photo © Simon Mills

The installations Where do birds go to hide (I) and (II) turns the encounter with objects freed from normative standards into a spectacle. A dead tree; animal bones; the skin of a taxidermy bird: each of these things on its own is mere debris. But when they are brought together, when they are grafted onto one another in such a way that creates relationships between them, they rise to a new status: that of an active encounter. They are given emotional value: these long-dead things become bodies with the capacity to affect and be affected.

In agricultural botany, a graft is a sprout inserted into a slit on a trunk or stem of a living plant, from which it receives sap. In medicine, it’s a piece of living tissue that is transplanted surgically to replace diseased or injured tis-sue. In the former, grafting is often used to create new varieties of a single plant, or an entire new species of plant. In the latter, grafts can sometimes be made between members of different species, that is, human and animal. In both cases, a new appearance, a new life is granted: when the sap, or blood, begins to circulate seamlessly through the organism, the graft has been successful. By performing the assemblage of fragile things, connective agency is first enabled and then allowed to flow. This is not a metaphorical association of signifiers; a useless corpse has no autonomous desire to be anything other than what it is. These encounters instead give us a glimpse into the power of matter.

Likewise, sometimes, a tree can morph and change its shape in order to host the fall of a dead sparrow (or is it only sleeping?).

— Ali Cherri

The Flying Machine, 2017

Installation made of wood, bamboo, crow wings, ropes and metal

270 x 700 x 200 cm (with wings spread)

Edition of 1 + 1 AE

Installation views: FIAC Hors-les-Murs 2017, Jardin des Tuileries. Photos © Ali Cherri ; MACLyon, 2020, Photos © Blaise Adilon.

As homage to dreamers, The Flying Machine installation looks back at the early dreams of flying, from Abbas Ibn Firnas to Leonardo da Vinci and the Wright brothers. Man has always dreamt of breaking the mold of formality of his body, in order to remain suspended in air and defy gravity. Flying machines went through different phases. First attempts of flying were done by using ropes against a series of pulleys of varying sizes in order to increase power. But soon, we learned that the gliding flight of birds, rather than wing motion itself, was the way to go for humans to achieve any sustained flight for an extended period. The next step would be not imitating nature at all but designing and building winged gliders exclusively by and for human use in mind. The dream of flight opens our horizon to listen, to feel the subtle movements of our soul, to feel the body breaking with its form, weight, organs, bound-ness,breaking and not fearing what this break may bring in the future.

The installation is comprised of a giant wing, made out of 100 taxidermy crow wings assembled together. My recurrent use of taxidermy arises from the complex reality it brings forth, as can be seen in the artwork Démembrement (2014). Taxidermy is a shape-shifter, easily sliding between categories of objects and between objects and experiences. Taxidermy was employed as a fallacious technology that simulates a communion with nature, thus offering a form of cure for the threats and decadence of modern life. As for crows, they are considered as totems and spirit guides associated with life mysteries and magic.

The wing will be suspended on what seems to be a prototype of a flying machine structure. Inspired by the early drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, the structure is made out of bamboo, with different ropes and pulleys holding the wing hovering above the ground.

The Flying Machine is a hybrid machine, bringing together elements of what we divide as nature/culture; the bamboo once a living plant becomes now a construction element, the taxidermy crow wing once a living flight organ is now pinned to the ground. The human and non-human, the organic and technological, carbon and silicon, history and myth, modernity and postmodernity, nature and culture, all these divisions and dichotomies appear here as inadequate for understanding our world.

The Flying Machine takes the shape of an unfinished project, a work-in-progress of some dreamer who, by observing nature challenges and puts our bodies in an impossible position: the human body is up in the air, defying gravity, breaking the law- a formality of movement.

— Ali Cherri

Petrified/Fragments (I), 2016

Installation includes Fragments (I), fragmentary archaeological artefacts, ethnographic objects, skull casting, taxidermy bird, light table, variable dimensions, unique, and Petrified, single-channel video, color and sound, duration: 12 min, edition of 5

Installation views: Aichi Triennal, 2016; Sursosk Museum, 2016.

Petrified/Fragments (II), 2016

Installation includes Fragments (II), archaeological artefacts, taxidermy bird, light table, variable dimensions, unique, and Petrified, single-channel video, color and sound, duration: 12 min, edition of 5

Coll. MAC VAL, Vitry-sur-Seine, France

Installation views: Matérialité de l’invisible, Centquatre, 2016. Photo © Marc Domage; Sursock Museum, 2017; Statues Also Die, Fondazione Museo delle Antichità Egizie di Torino, 2018.

Ali Cherri’s work, Petrified/Fragments, consists of a video shot in a wildlife park and an archaeological museum in the United Arab Emirates, and an installation of objects gathered on a light table.