Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

In resonance with the powerful anti-racist movement that has toppled statues of settlers and slavers around the world in the summer of 2020, Sammy Baloji tenaciously explores colonial archives in order to undermine their authority and uncover hitherto inaudible stories. Kasala: The Slaughterhouse of Dreams or the First Human, Bende’s Error gathers a series of works in which collection and museum archives tensely relate to Luba transmission practices. For years, Sammy Baloji has juxtaposed colonial images with the experience of the people from southern Congo regions devastated by mining. He now articulates them through multiple mediums: digital collages printed on mirrors, film, scarified hunting horns, and an interactive digital touchscreen.

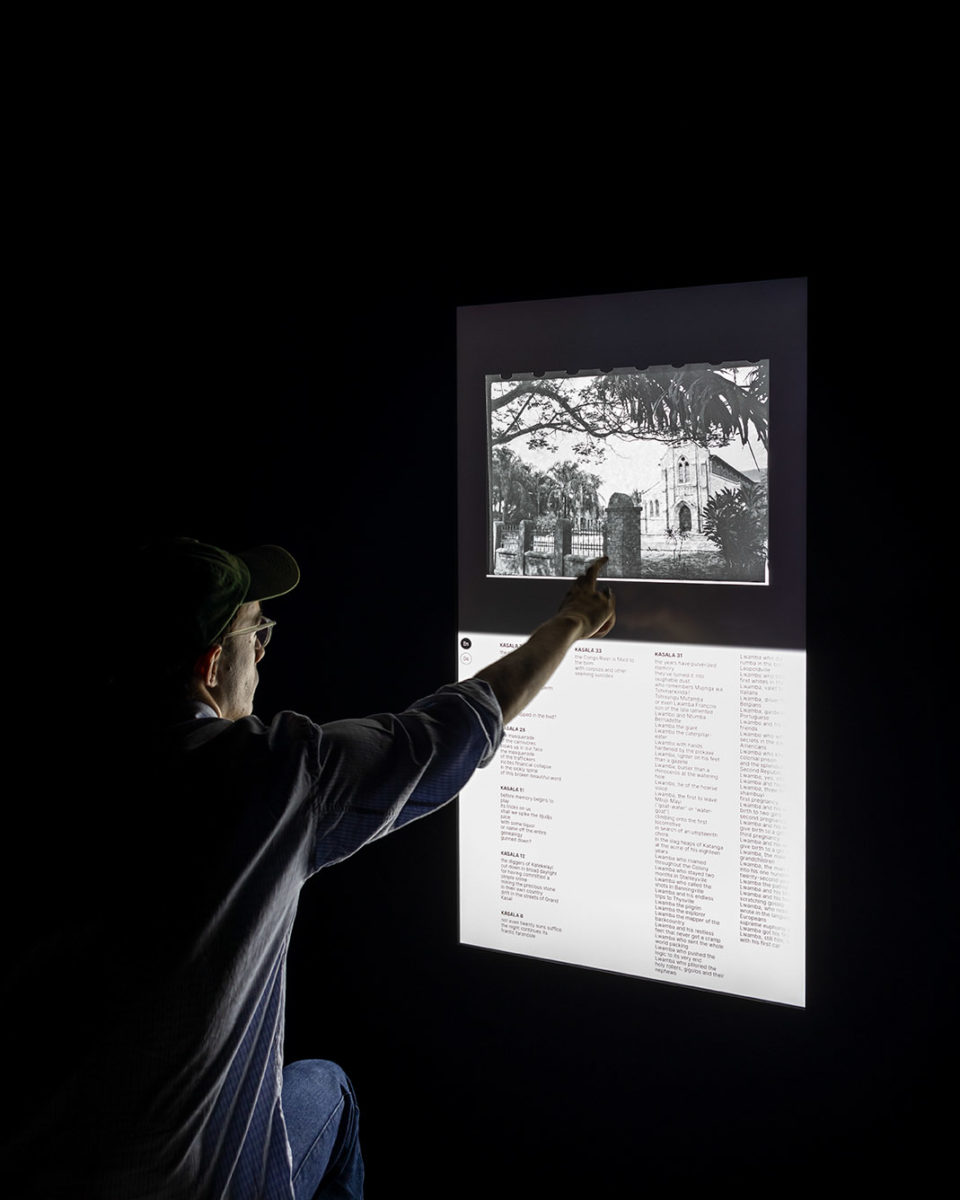

The exhibition’s starting point is Sammy Baloji’s critical questioning of German ethnologist Hans Himmelheber’s (1908-2003) photographic archives, which include pictures collected in 1939 during a trip to the Congo, then a Belgian colony. These photographs, which are today conserved in Zurich, are considered novel from an ethnographic perspective because Himmelheber was interested in the Congolese people as creative individuals. In a series of collages on mirror discreetly referencing divinatory nkisi figures, which place viewers in front of their reflection, Sammy Baloji associates some of these photographs with images generated by X-Ray scanner of various objects from the ethnologist’s collection.

By replicating the use of a visual technology commonly employed by museums to visualize the material structure and hidden content of objects, the artist questions the knowledge gained through such medical imagery. He opposes a counter-narrative to the translocation of artifacts that separates them from their use and cultural meaning: invited by Sammy Baloji, the writer Fiston Mwanza Mujila created a Kasala, a Luba poem combining the recitation of elements from the genealogy of a celebrated person with mythological, cosmological and historical fragments.

Accompanied by two musicians, Patrick Dunst and Grilli Pollheimer, the writer recited his text at the inauguration of the exhibition Congo as Fiction – Art Worlds Between Past and Present at the Rietberg Museum in Zurich, in 2019. Within the layout of the exhibition of so-called ‘ethnographic’ artifacts, such as masks presented in showcases, this performance disrupts the tranquility of this stylized display of objects. Going beyond such de-contextualization which silences objects, the Kasala brings in the “missing voices.” Painful voices though, as they express the sufferings of Katanga’s artisanal miners, the bloody repression of liberation movements, the long list of political murders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, from the prime minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961 to Thérèse Kapangala, an activist who took part in protest marches against the Joseph Kabila regime and was killed by the Congolese army in January 2018. Fiston Mwanza Mujila links the polyphony of these stories with an evocation of Bende’s error. Bende is a legendary founding figure of the Luba tradition, part-god and part-ancestor. In crescendo, the writer’s voice resonates with the instruments. It quivers, leaps, whispers and enchants before finally trailing off, drowned by the turbulent tale of a violent present shaped by frustrated rebellions, deaths, funerals and constant mourning.

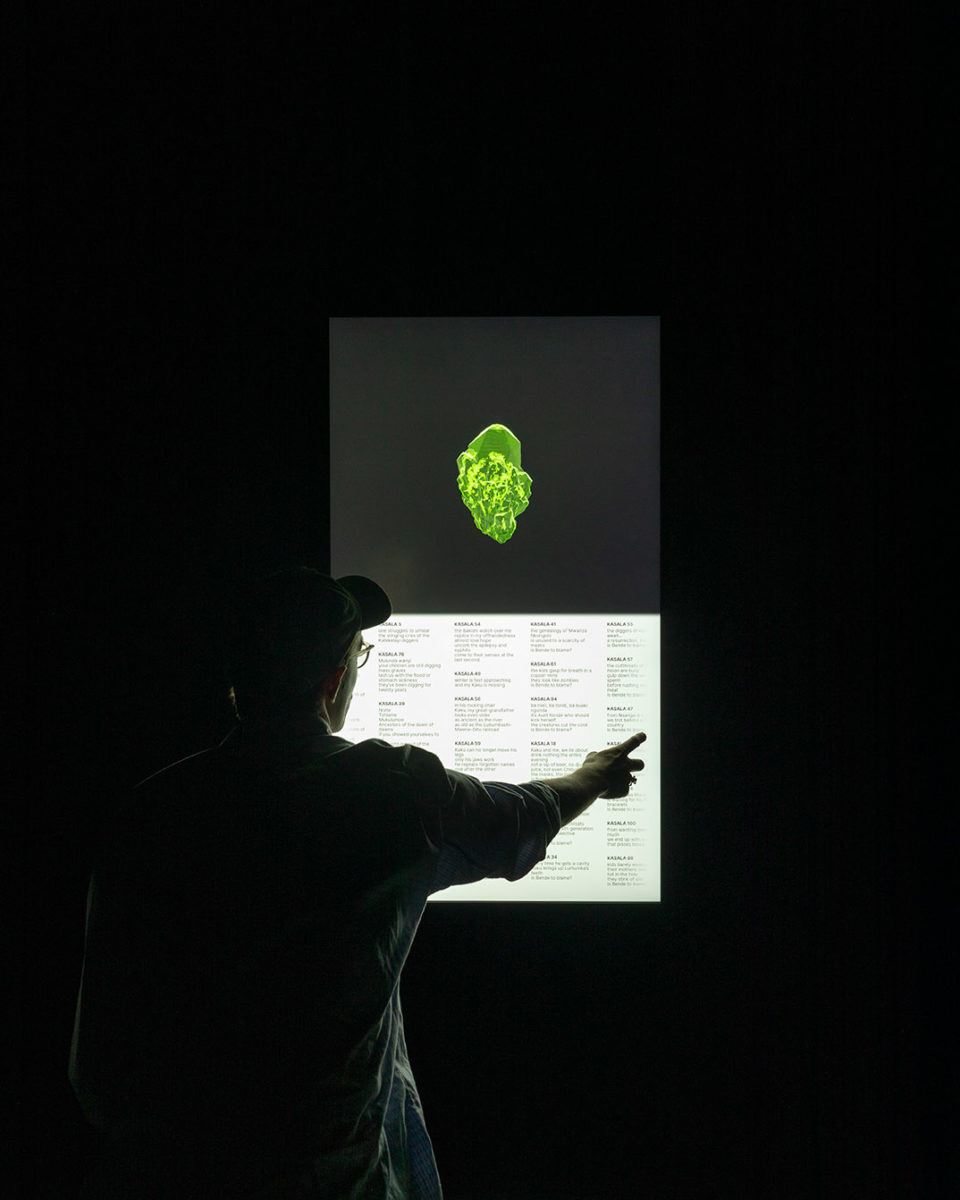

The performance is but one element in the multiple possible versions of a history whose components are varied. The exhibition conserves its traces and re-articulates them through an interactive digital touchscreen which enables visitors to rearrange the order of the Kasala and thus intervene in the making of history. The work transposes in the digital sphere the Lukasa, a mnemonic board used by the Luba people in Katanga, and thus recalls the extent to which contemporary communication and memory depend on mineral extraction1. Indeed, minerals from the Congo, such as coltan and copper, are key components of digital appliances.

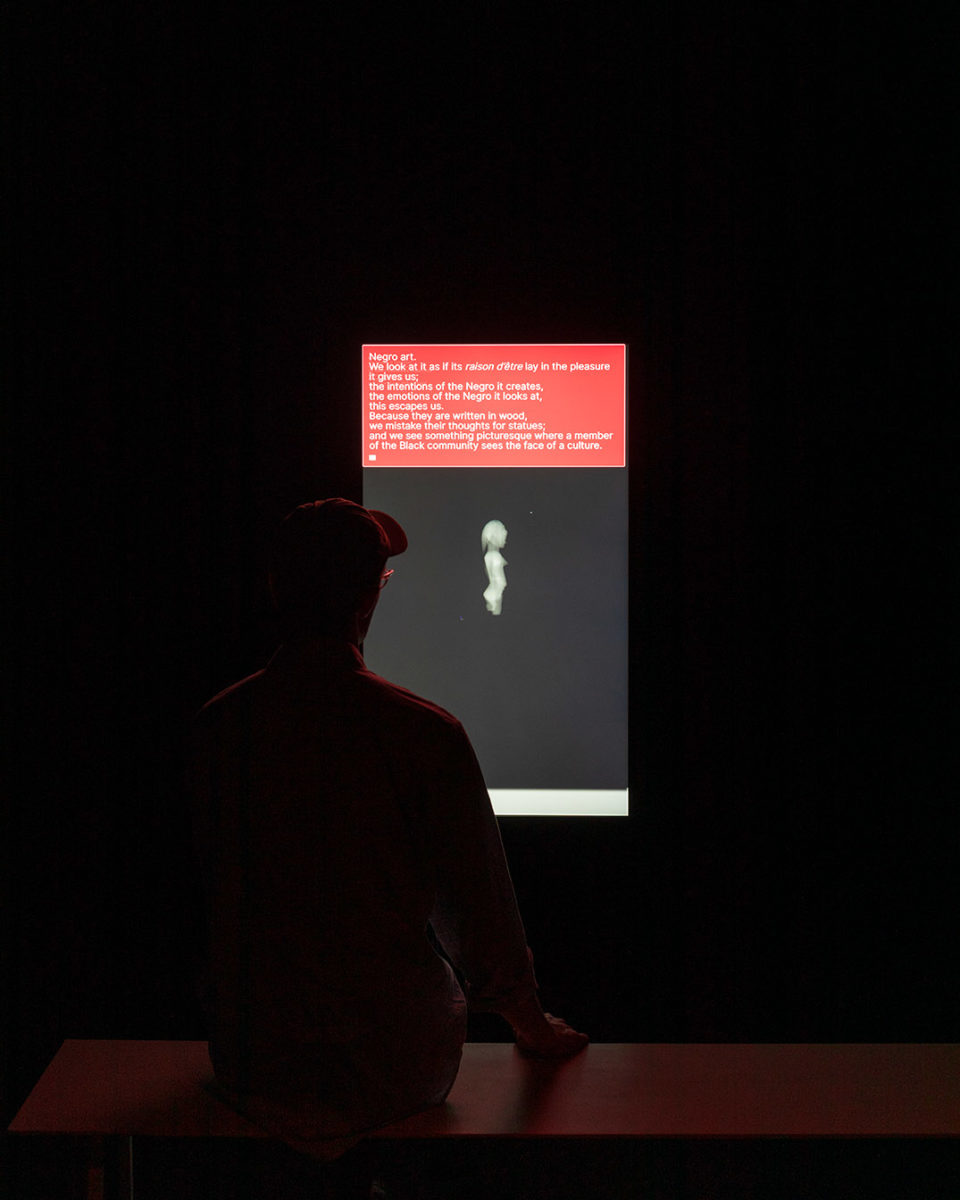

Another variation of this tale is a film that intertwines the capture of the performance, the images obtained through X-ray scanner, and 3D models of objects from the museum collection combined with quotes from a famous documentary, Statues Also Die (Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Ghislain Cloquet, 1953), which describes the colonial museum as the culmination of the destruction of living cultural practices.

In a new series that furthers this analysis into present times, Sammy Baloji superimposes on a selection of photographs by Himmelheber digital models of minerals from Katanga. He thus combines the destructive impact of mining in Congo with the history of colonial collecting and signals the aspiration to absolute control enabled by the digital technologies used by museums.

Once more, Sammy Baloji associates collection and hunting: the exhibition also shows a photograph from the archives of the AfricaMuseum of Tervuren. In the center of a bourgeois living room decorated with hunting trophies, a musical instrument is fixed on a wall. It is a hunting horn, which highlights the predatory character of middle-class opulence whose violence unfolds outside of the frame. In counterpoint to the photograph, Sammy Baloji displays a scarified hunting horn in a showcase that signals both the museums’ domestication and the silent incommensurability of artifacts. In this work, the object is shaped after the photograph: the colonial archive generates the artwork and adds a gesture of resistance. In scarifying the instrument, Sammy Baloji uses a secret and codified language that resists colonial deciphering. Although the scarification is manifest on the object’s surface, its meaning goes way beyond its ornamental aspect and is reserved for the initiated, which imposes a limit to the domineering, absolutist and voracious ambitions of the colonial classification.

—Lotte Arndt, June 2020

1. The Lusaka is traditionally used by the Mbudje who is initiated by those who hold the memory of the kingdom in order to perform the kings’ genealogy and prowesses.

Exhibition journal

Sammy Baloji présente son exposition à la galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2020