Introduction

This exhibition by Ninar Esber and James Webb introduces different forms of disobedience that tend to thwart the systems of societal domination. The defiance these two artists address towards the underlying censorship within the moral and technological codes of our era of emergence proposes symbolic mutation as a possible means to resist these systems. Ninar Esber and James Webb display a clear and fleeting vision of our behaviours, borrowing the theatrical form of the Ishtar Gate in one case, and diverting our mobile phones without our knowledge in the other. This proposition questions the transformation of the relations in which we exist, and therefore the question of resistance so aptly developed by Foucault: “how is it possible to produce positive mutations in the global biopolitics of bodies and subjects? This question immediately implies major self-critical work, on the conditions of one’s own thinking process, on one’s relation to others, on the conditions and consequences of our own existence”.1

— Cécile Bourne-Farrell

Since the early 2000s, Ninar Esber has developed a protean and political artistic practice. Through performance, video, photography and sculpture, the artist points out the discriminations and inequalities that are generated by patriarchal systems. She pays particular attention to the status and role given to women in the Middle East, in Europe or elsewhere. She willingly lends her body to highlight the absurdity, hypocrisy, violence and injustice that women and so-called minorities are subject to. Ninar Esber systematically instills a formal rift from these difficult subjects. She manipulates the seductive effects at play, stirs our curiosity, and encourages us to reflect upon our relations with others.

The Triangle for Women who Disobey project is articulated around an eponymous video work made in 2012. A series of fatwas and laws directed towards women in the Middle East and worldwide appear one after the other on the screen. The artist collects and reveals patriarchal injunctions that govern the existence of women who must never show their face, travel alone, like bananas, like women, be politically active, claim that they own their body, think they are equal to men. The prohibitions that vary according to each country fuel the oppression and the control of women. Extracted from their context and accumulated this way, they convey a certain suffocation. This discomfort is prolonged in the title of the work, which refers to the geometric form of the triangle. This is approached in three ways: musical (Jacno, Triangle, 1979), historical and symbolic. From a historical point of view, it recalls the Nazi signs during the Second World War. Whereas the yellow star is the most well-known in collective memory, other coloured triangles have allowed for various differentiations (religious, racial, sexual, ethnic). Always facing down, the triangles can be split into black for Gypsies, prostitutes or lesbians; pink for homosexuals; red for political resisters; blue for emigrants. Symbolically, the upside-down triangle evokes a woman’s private parts. As a feminist symbol since the 1960s, particularly since Judy Chicago’s artworks, this shape carries stories of stigmatised communities. As such, these drawings, in which the fatwas are transcribed in coloured pencil and accumulated to form different coloured triangles, are lodged in a firmly established feminist art heritage.

In addition, triangle after triangle, the stories and experiences constitute a luminous and multi-coloured gate, inciting disobedience and resistance. The silhouette of Gate of Disobedience is inspired by the Ishtar Gate, one of the eight gates of the inner city of Babylon (586 B.C.), which was erected in honour of the Assyrian goddess. She was feared since she incarnated life and death, but also harmony between the feminine and the masculine. Ninar Esber chooses this symbol of authority and balance to highlight all the past and present outrages committed against minorities. A proud sign, the gate is proof of the persistence of a daily fight.

— Julie Crenn

James Webb explores the nature of belief through dynamic and innovative modes of transmission, all the while summoning the viewer’s capacity for wonder. In order to achieve this, he employs humour, diverts the usage of common technologies, and strategically develops his artistic vocabulary in accordance with each situation he works in.

James Webb has participated in the 9th Lyon Biennale, the 3rd Marrakech Biennale, as well as in the recent Venice Biennale. He has presented projects at Domaine Pommery, a telephonic intervention2 at the Palais de Tokyo, and took part in the exhibition “No Limit” at Galerie Imane Farès in 2012. During various residencies (like at the Darat al Funun3 in Amman), he has worked on projects in the public sphere. His latest commission was an audio guide for a cemetery in Stockholm4. For several years, he has been compiling a worldwide audio archive of interfaith prayers. Significantly he works between languages and beliefs in a response to his childhood, which was marked by the height and the end of apartheid.

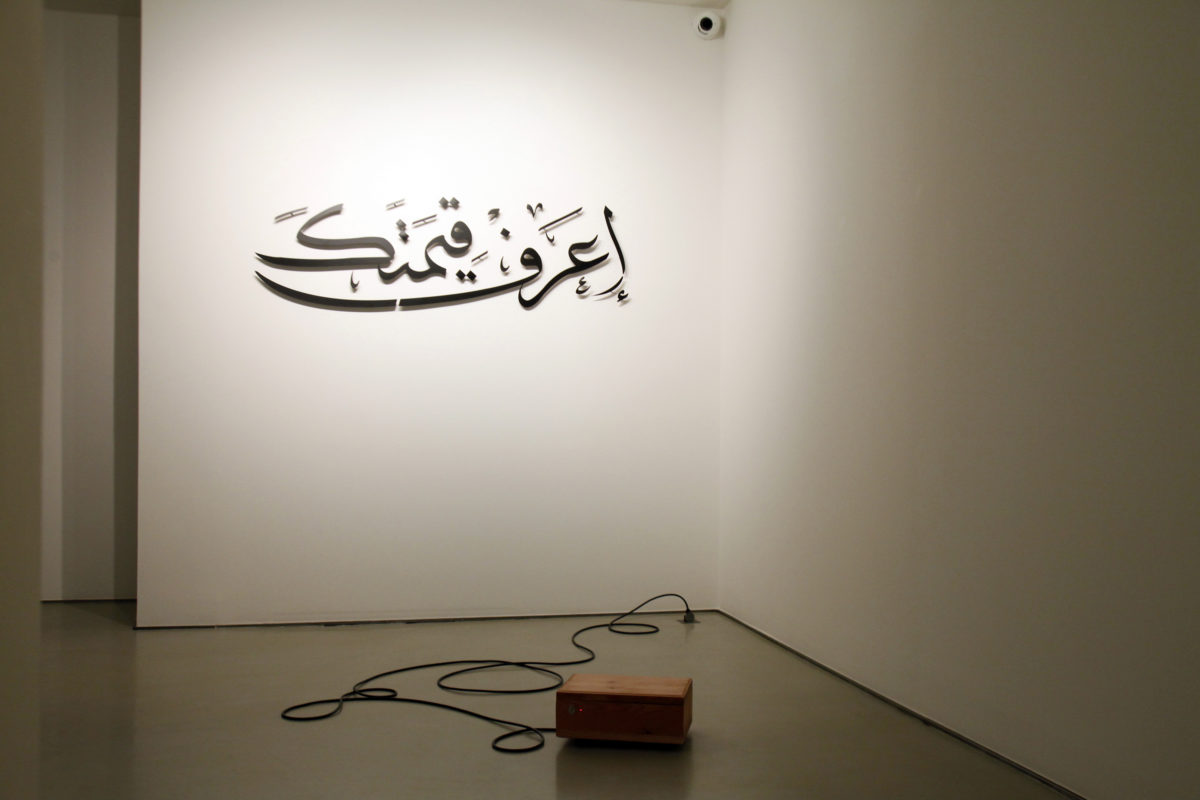

In a multidisciplinary way, James Webb focuses on the most intangible of forms such as sound, light and connectivity by modifying the function or the reception of the place where he is asked to intervene, rather like in the artwork exhibited here called Spectre. According to Sean O’Toole, one of the first South African critics to write about his work: “He can make light and sound theatrical to the point that they also evoke their own dysfunctions.” It is with great ease that James Webb merges fiction and theatre, to the extent that we start to believe that even if a space seems to have a specific function, everything is reversible. As Webb underlines: “I am fascinated by the dynamics of belief, not just in a religious, theatrical and social way, but also in an art historical and economic way. I never studied art or music at university. Instead, I read for degrees in Drama and Comparative Religion. I also obtained a diploma in Copywriting. These three subjects, along with an appetite for cinema and experimental music, are keys to my contemporary art practice.”

The video entitled Le Marché Oriental involved inviting an Imam5 to sing the call to prayer in the remains of an Apartheid-era building that functioned as a segregated market called The Oriental Plaza before its demolition and transformation into luxury apartments. This artwork places the viewer inside the place which is destined for destruction, bathed as it is in a perfect but worrying tranquillity, which is that of the resistance echoing all the imposed and suffered injustices. The person reciting the Adhan is never revealed, the absence transcends daily reality giving these moving images a spiritual dimension prior to the erasure of any trace of this dark period in South Africa.

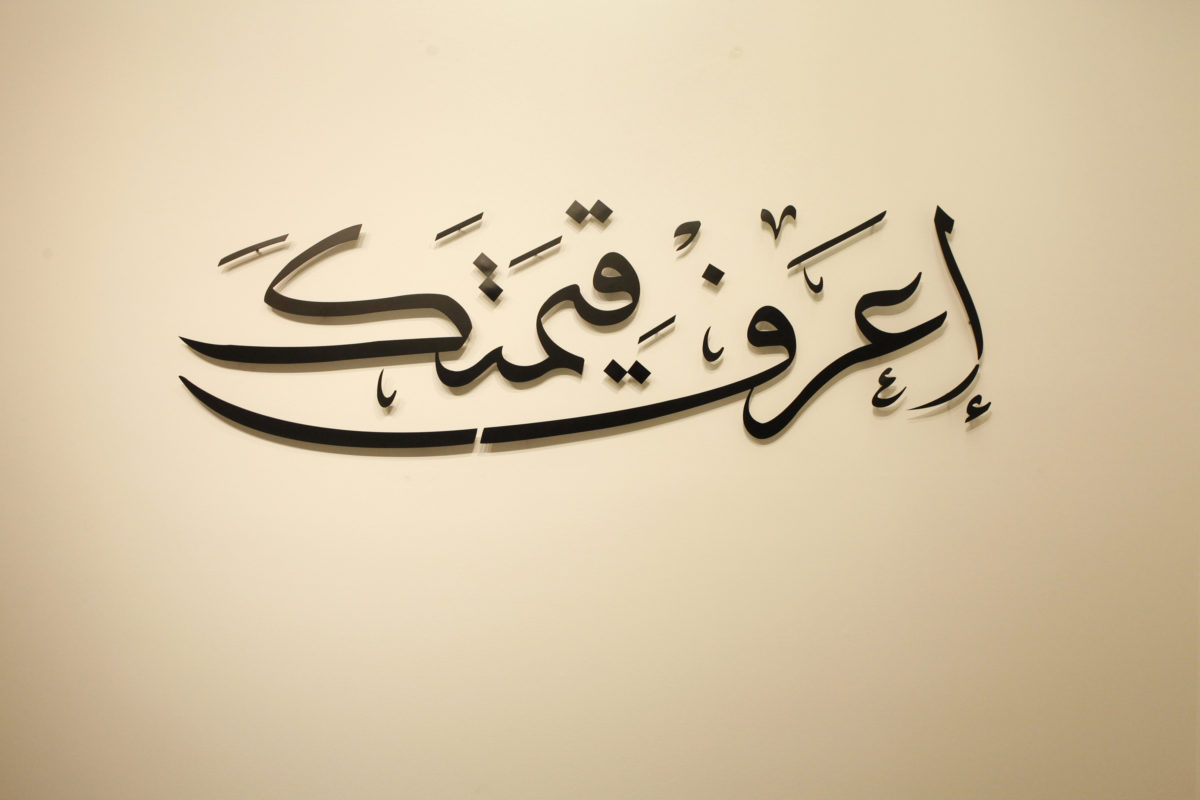

James Webb says: “My interest in religious belief has to do with how we articulate our position in the universe, how we choose to give certain things power”. This is how I would introduce Know Thy Worth, a work that relates to the value we bestow on ourselves. Somewhat cynically, this ancient saying reviews the concept of capitalism and self-evaluation. The Greek aphorism “Know Thyself” decorated the entrance to the oracle in Delphi, where the priestess Pythia officiated behind a veil, understood here as reference to the subtraction from representation, a disembodied voice whose esoteric associations are still so praised. This specially hand-written5 modus operandi evokes finance and self-worth, a speculative metaphor to encourage a particularly vigilant and receptive state.

— Cécile Bourne-Farrell

1. Foucault Michel, “Naissance de la biopolitique – résumé du cours au Collège de France” in Annuaire du Collège de France, 79e année, Histoire des systèmes de pensée, année 1978–1979; Dit et écrits. Vol. III, Gallimard, 1979.

2. https://soundcloud.com/theotherjameswebb

3. http://www.daratalfunun.org/

4. The cemetery of Skogskyrkogården in Stockholm: www.letmelosemyself.com

5. Sheikh Mogamat Moerat of the mosque of Six’ Zeenatu Islam Majid