Younès Rahmoun’s artworks take their meaning, once inscribed, in a worldview based on Sufi philosophy. His entire approach that seeks to reconcile artistic and spiritual practice is a variation on the concept of harmony, principal of cohesion between beings and their environment. Marked by faith and turned towards meditation, the artist does not look to represent it but rather to suggest its presence, evoke its spirit. He attempts to shape what has no form, make the immaterial material and reveal the invisible side of things. “I seek to give form to the invisible, impalpable, like faith, the soul, the spirit, awakening,” he explains. To achieve this he tries to transcend matter, infuse each object with life and lightness. Everything comes into play: light and colours, symbols and numbers, orientation and direction of shapes in space.

His first works already reflect this spiritual dimension in the image of Ghorfa– literally ‘room’ in Arabic. Ghorfa, he says, “is a room which brings together a lot of ideas. I believe that everything I have learned, through my artistic and spiritual research, can be found inside. (…). It is therefore a reproduction of this small room given to me by my mother in 1998, and in which I thought, worked and meditated for seven years. This bedroom in my parents’ house in Tetouan was my place of refuge, a place whose story is entirely linked to mine. Transforming it into a life-sized sculpture is a way of inviting the spectator to enter into my narrative”1. At once a living space, creative workshop and meditation space, Ghorfa thus connects the artist’s intimacy with the world by creating a zone of contact between his spirit and that of others. In this way, theproject translates the action of living according to a dual movement: it allows the artist to inhabit the world and in turn encourages the world to come live in it.It is this implicit richness of the lived architectural space, embodied, reflected on and imagined, that Younès Rahmoun explores again here, in the context of his exhibition Manzil (house in Arabic).

For Younès Rahmoun, building a house is about using the space to physically live in it but also occupy it mentally. Indeed, he calls upon his spiritual experience, his imaginary but also collective memory, to adapt his idea of the home to different objects and experiences. Manzil-Batn is an oval cell in terracotta, secret and open, mysterious and simple. It is a shelter, an absolute refuge, a nest in the world, and an image of peace. It is a daydream, an invitation to imagine and project ourselves into the mystery of being. It evokes “sojourns of being”, “homes of the being”, where a certainty of ‘being’ is concentrated”. It is a “reverie of living in inhabitable places”2. Thus this precarious and fragile refuge is potentially a dream of home. A hideout from life, a hideout for life. The centre of a universe. The act of building by the artist, and this gesture of poetry, now evokes what is in us, and more than us. “Living dreamlike in the birthplace, is more than inhabiting it by memory, it is living in the disappeared house as we dreamed it”3 states Gaston Bachelard. Yet this “poetics of space” – parallel to the poetics of building- corresponds with poetics of the body, its experience and its apprehension of space.

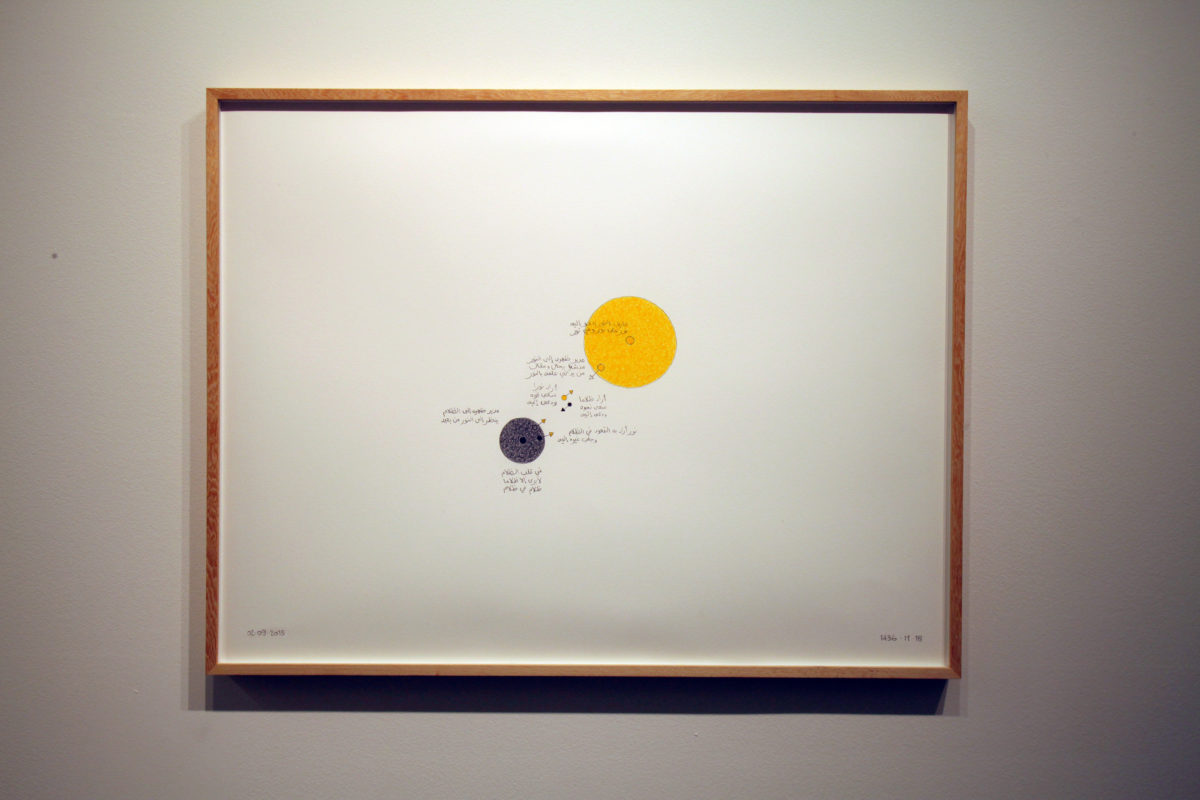

Indeed, Manzil-Ghorfa embodies the relationship of the body to the world. It is an envelope. A metaphorical body. It is a place of natural life. Interior and exterior blend in an ambiguous connection modifying our perception of body but also of space. It is an experiment. It invites a spiritual journey, of the body towards the heart and of the heart towards the universe. This journey is infinite. Yet, this migration of one to the other, from interior to exterior and vice versa, is also a migration from one place to another, from darkness to light, as evoked in the drawing Nôr-Dalam-Nôr.

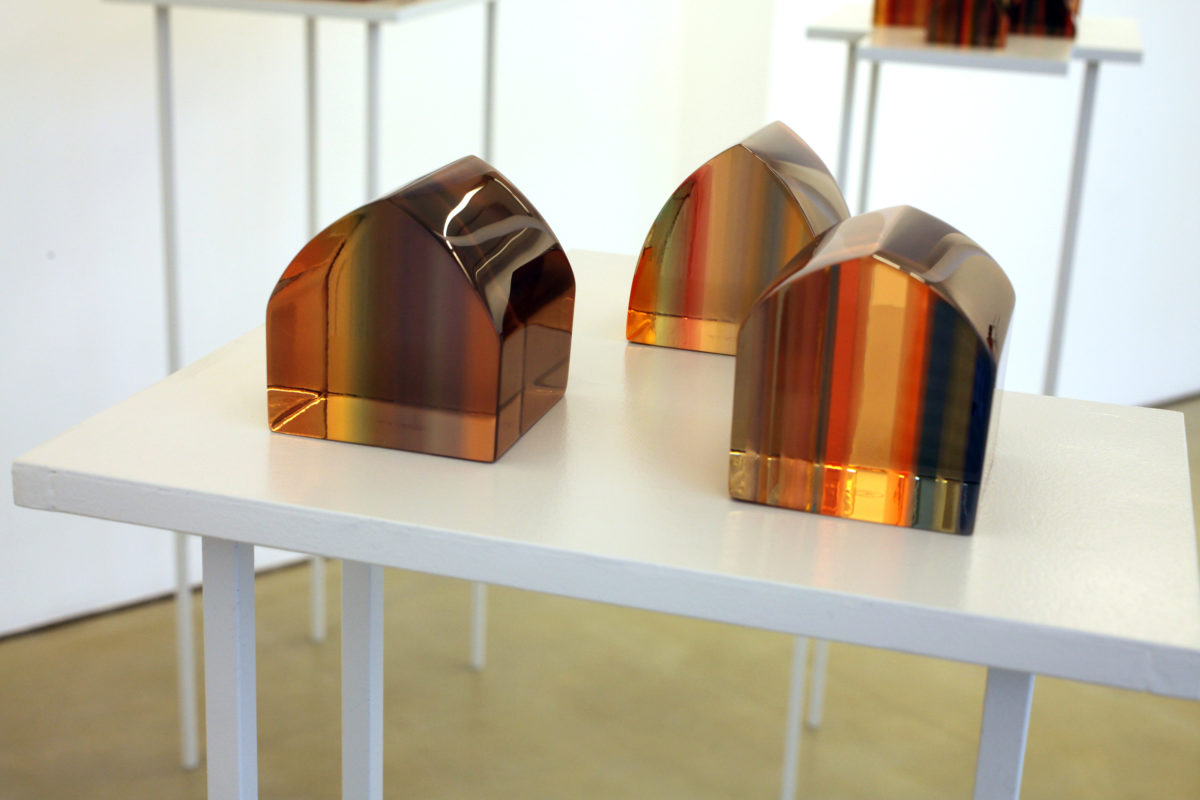

Patches of light, patches of colour: Manzil-Lawn are small houses. Brief forms of habitat. Imaginary constructions. Made of resin, an opaque and translucent material, they reveal themselves in the light. According to the artist, from this light they radiate a pure colour, which is the essence of the universe. As poetic objects, their number also evokes the 77 branches of the Muslim faith, precepts dictated by the exegesis and speech of the prophet (hadith). From this game of repetition in form and colour, these houses represent unity in diversity. They also metaphorically evoke “the body inhabited by light” the artist declares. Manzil-Lawn thussuggests the ability of beings to shine – through a dual movement inside and outside – of an infinite light.

This exhibition allows Younès Rahmoun to enter into an intuitive and intimate relationship with the world. It is in itself conceived as a “corner of the world”4. A poetic space that contains a powerful imagination. It is indeed an intimate space, a refuge, a setting, a place of exchange but also a living space open to the world.

— Mouna Mekouar

1. Interview with Younès Rahmoun by Jérôme Sans, Paris, 2007-2008. Published in the exhibition catalogue Zahra, Sala Verónicas, Murcia 2009. Curator : Jérôme Sans.

2. Gaston Bachelard, La Poétique de l’espace (1957), PUF, Paris, 1994, p. 19.

3. Gaston Bachelard, op. cit., p. 35.

4. Gaston Bachelard, op. cit., p. 24