Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]Photo © Tadzio

[+]Photo © Tadzio

[-]

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Exhibition view

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Photo © Tadzio

Pictures

For many years, Mohssin Harraki has been exploring the often politically engaged themes of genealogy, the Islamic Enlightenment and mathematics. Trained at the National Institute of Fine Arts of Tetouan, he was a student of artist Faouzi Laatiris who developed a conceptual vein that is resolutely rooted in reality. Hybrid aesthetics and strong transmission principles imbue the art of a whole generation of students, such as Younès Rahmoun, Mustapha Akrim and Mohssin Harraki.

The latter is keen on developing a pedagogy of the image, which is to say that his artworks do not hide behind appearances but claim to be conceptually legible. The titles and accompanying texts bring immediate clarity and understanding when in the contemporary art world, the bright and loud semantic radiance of an artwork’s paratext can obscure the meaning even when it is meant to be crystal clear.

Mohssin Harraki’s new body of work exhibited in Illusions explores these artwork-reading systems. He sets out a simple speculative principle: similarly to proliferating cells, images are self-consuming. At a time when images are ubiquitous, it is increasingly difficult to produce more and more of them. Ever since the inven-tion of the printing press and photography, the subject is called into question while remaining relevant. At any given time, new images are created and no slowing down is contemplated or even possible, as if there was a constantly expanding data Big Bang. This observation naturally leads to one question: how does an image survive in a saturated world?

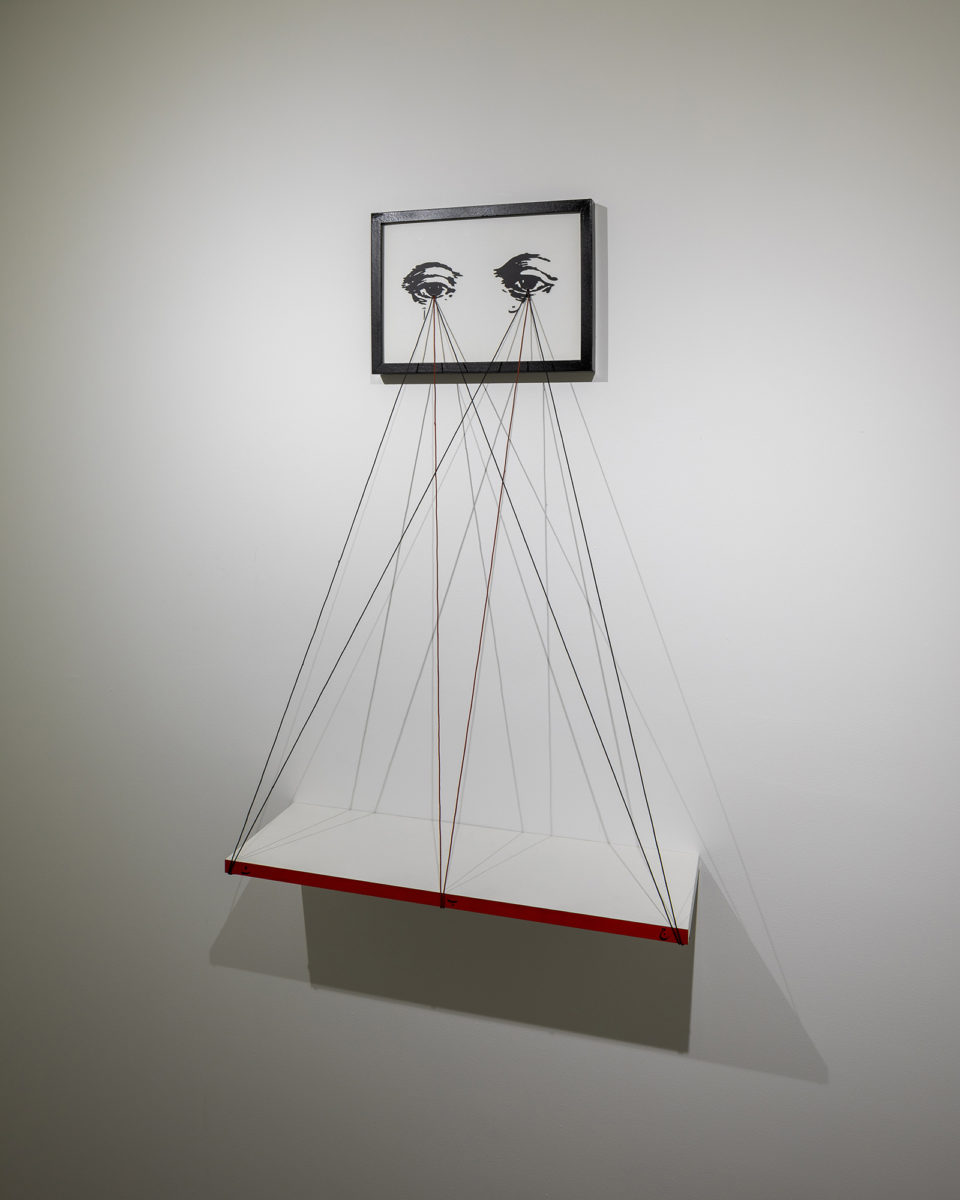

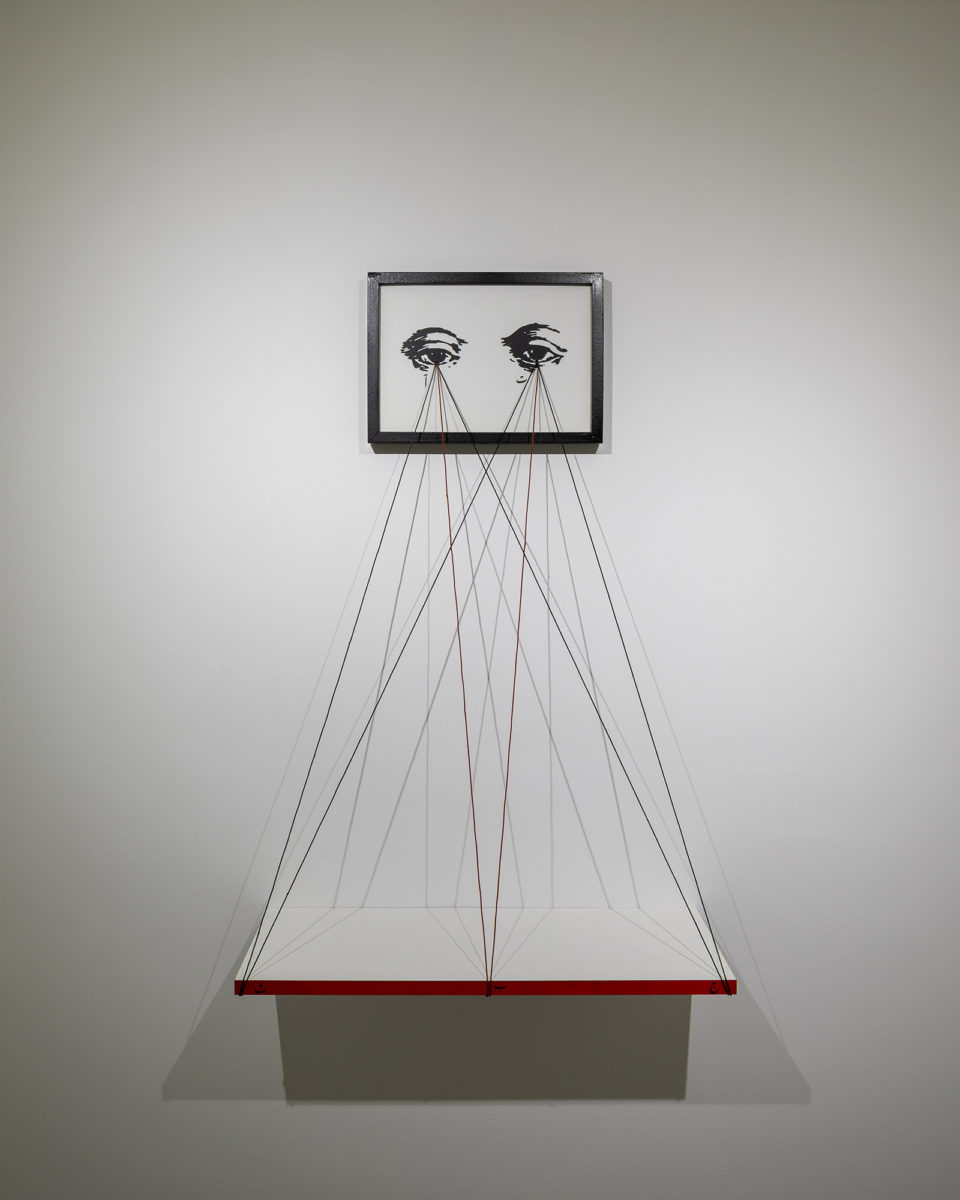

Mohssin Harraki has always been fascinated by history. In his new investigation, he analyses the history of the image, particularly that of photography. His starting point is linguistical: indeed, there is no word in Arabic for photography. The word ‘image’ exists but there is no proper term for photography. This has led Harraki to study the emergence of this medium—which linguistically is a stillborn ghost—through the examination of its various technical processes. Linking the issue of the future of the image to its physical origin, the artist decided to gather a body of historical photographs and reevaluate them by reworking on them. By appropriating what already exists, he avoids the thorny issue of the production of new contents. Harraki says that his interventions are akin to research and focus on “a discrepancy in reading and a shift in the gaze.” This research uses sparse resources: photographs, some of which taken from the weekly Le Miroir published in France between 1912 and 1920, are paired with lettering or geometrical forms. The selected images show scenes taken during the First World War, far from the military front. By using the captions of the historical photographs, Harraki seeks to erase the time distance that separates us from the moment when the discourse is stated, such as in the slogan “Feminism progresses every day.” In doing so, he asserts that some social issues such as feminism and war remain topical and eternal. He thus guides the viewer’s vision. With diagrams and signs, Harraki defines a new image he has not produced physically but built mentally.

Mohssin Harraki readily uses mechanisms at play in optics, sociology or geometry. In the Illusions series, he uses for instance the Müller-Lyer illusion that shows an effect which contradicts the principle of mathematical and conceptual equality. It shows two same-length segments, each with an arrow at both ends. The arrows are turned inwards in one segment and outwards in the other. We perceive the length of the two segments to be different even though they are perfectly identical. In the case of the Müller-Lyer illusion, the principle of equality can be read at different levels, i.e. mathematical or social equality. If different kinds of opti-cal illusion, such as anamorphosis and trompe-l’œil, have been known since the 14th century (for example in Piero della Francesca), they are rarely included in works of art in the form of signs, as with Harraki. Schemes that defy visual perception are associated with images with which they share no apparent link. The artist doesn’t only transform the image from a technical pers-pective but he also enriches it with a new signifying opening.

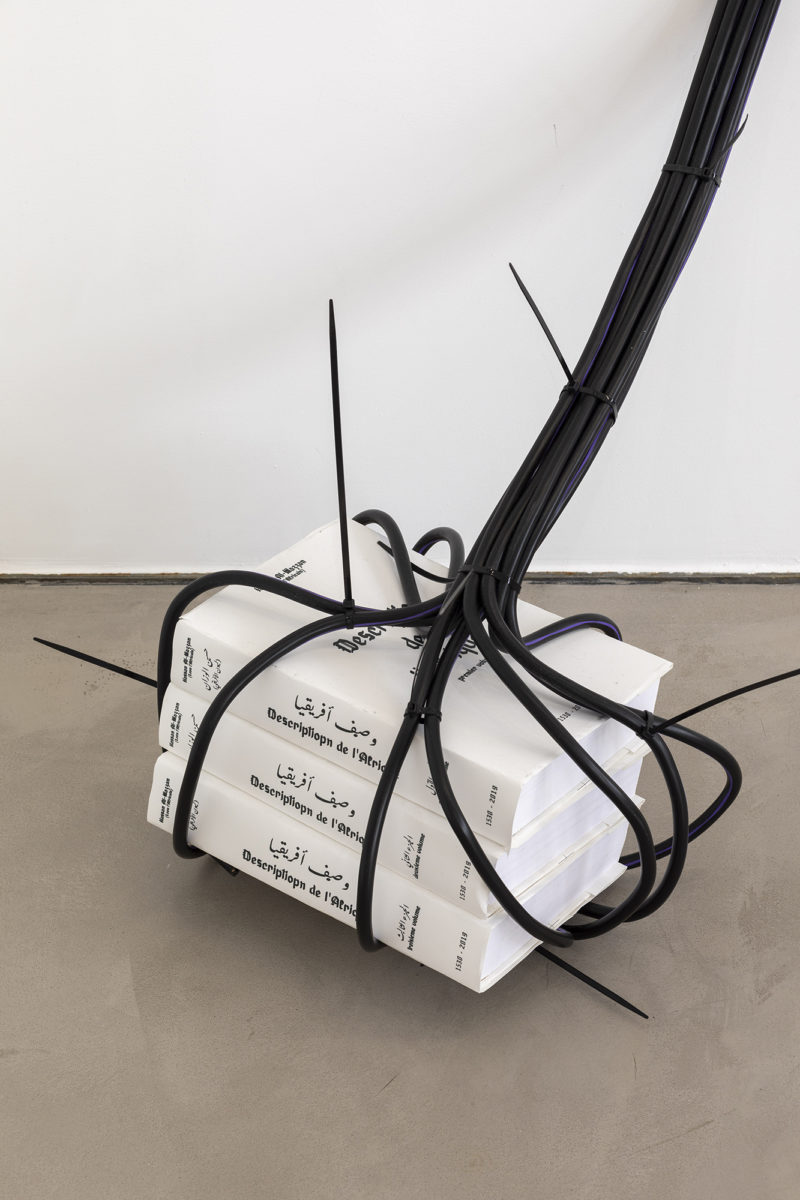

The main research theme of the Descriptions de l’Afrique (Descriptions of Africa) series is the history of the emergence of images. Harraki uses illustrations by Leo the African, a 16th century Muslim explorer and diplomat who converted to Christianity. Now largely forgotten, Leo wrote Cosmographia de l’Affrica, a reference book describing Africa that was widely disseminated at the time and contributed to building the legend of Timbuktu among the European public. Although the human being is traditionally rarely represented in the history of Islam, it is so with Leo the African. Harraki adds new layers of meaning by reproducing the illustrations that accompany the text on concrete blocks, which are an ambivalent medium.

Concrete blocks are produced on an industrial scale and have become a material of choice for the construction industry in Maghreb, replacing local resources commonly used before. By using this architectural element, Harraki highlights a new tradition: that of a material from the ‘cheap culture’. The main advantage of concrete blocks is their ease of use, but they are symptomatic of the loss of a type of patience and durability in the art of construction, now replaced by immediacy and the ephemeral. The artist considers that this material symbolises “colonial efficiency”, which also destroys local know-how.

This text is titled after a group show organised by Douglas Crimp in 1977, Pictures. In an article also titled Pictures on the postmodernist photographic activity, Crimp writes: “We are not in search of sources or origins, but of structures of signification: underneath each picture there is always another picture.”1 This sentence perfectly highlights the challenges of Harraki’s current investigation, which in the end is very close to the appropriation practiced by the 1970s and 1980s artists Crimp refers to. With his diversions and codes, Harraki reveals some of the paradoxes associated with history and creativity.

— Loïc Le Gall, December 2019

1. Douglas Crimp, “Pictures”, in October, Vol.8, Spring, 1979, p.87

Exhibition journal