Overview

[+]Overview

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Overview

[+]Overview

[-]Overview

[+]Overview

[-]Overview

[+]Overview

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]Details

[+]Details

[-]

Overview

Details

Details

Details

Details

Overview

Overview

Overview

Details

Details

Details

Details

Details

Details

Details

Details

Details

“Hijra”, between mountain and dust, in search of the size of the heart

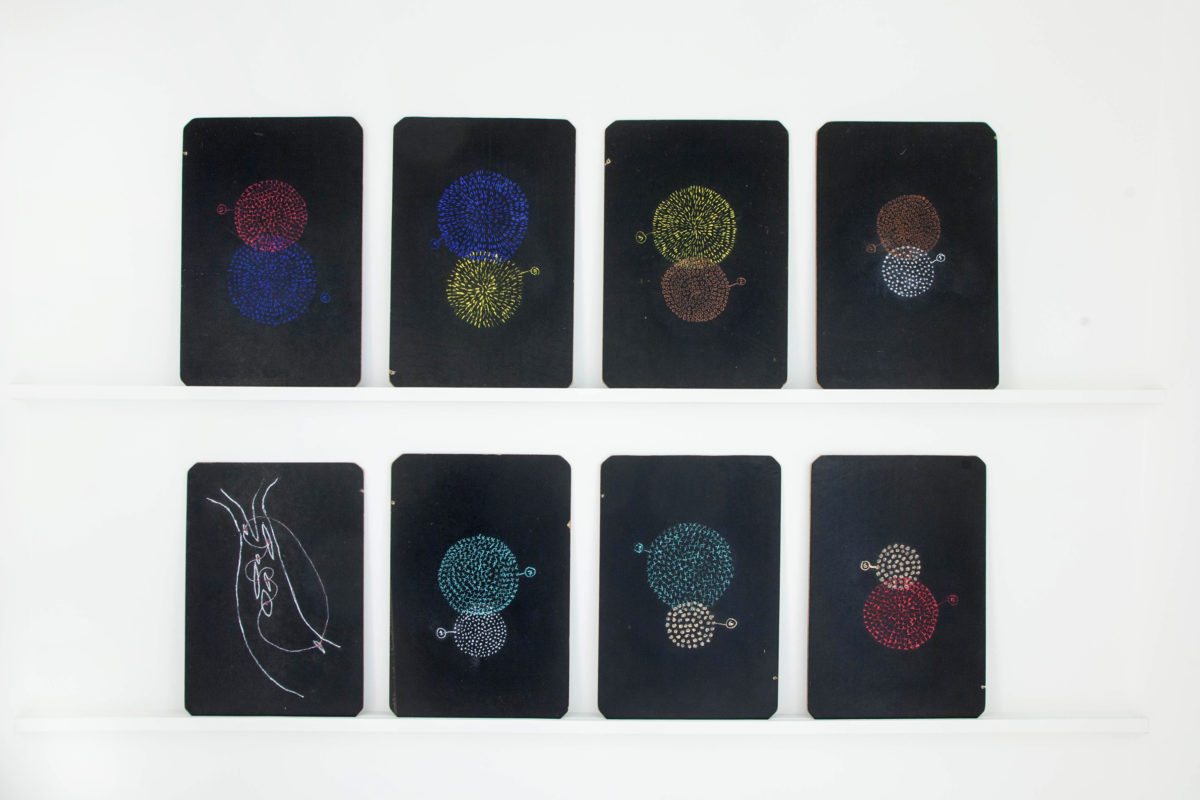

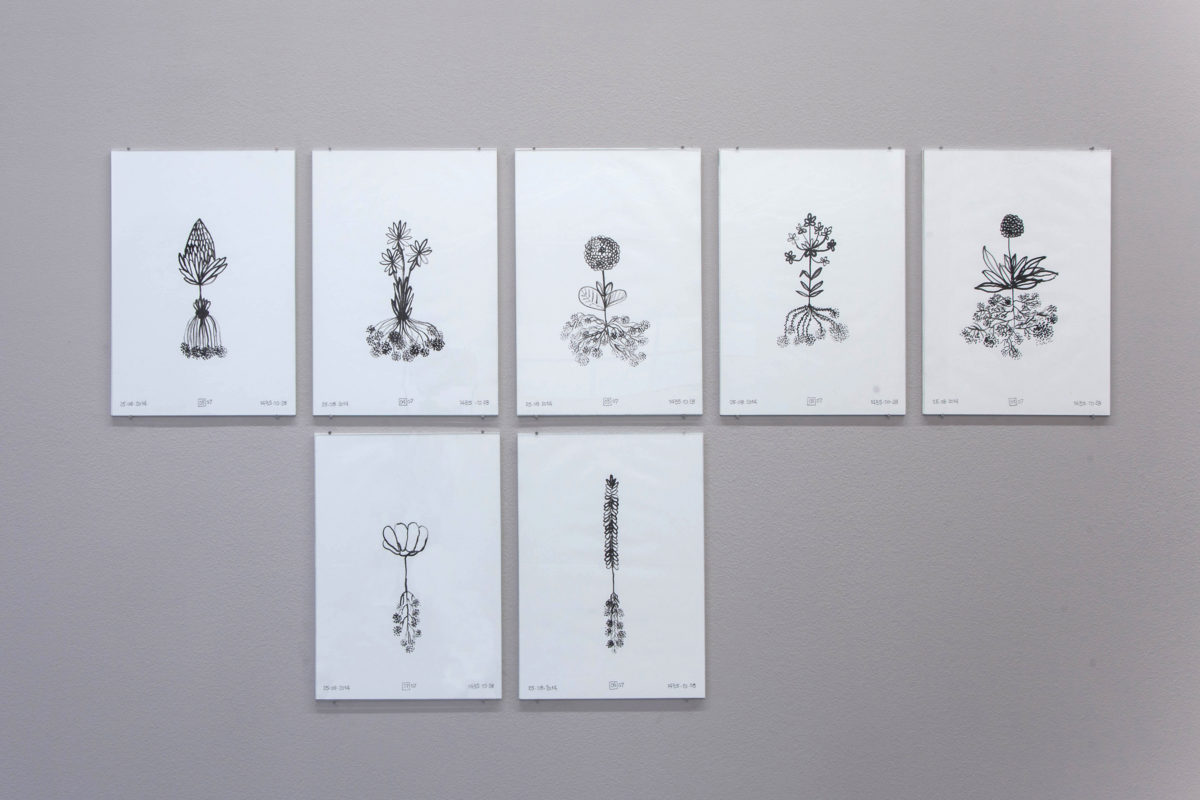

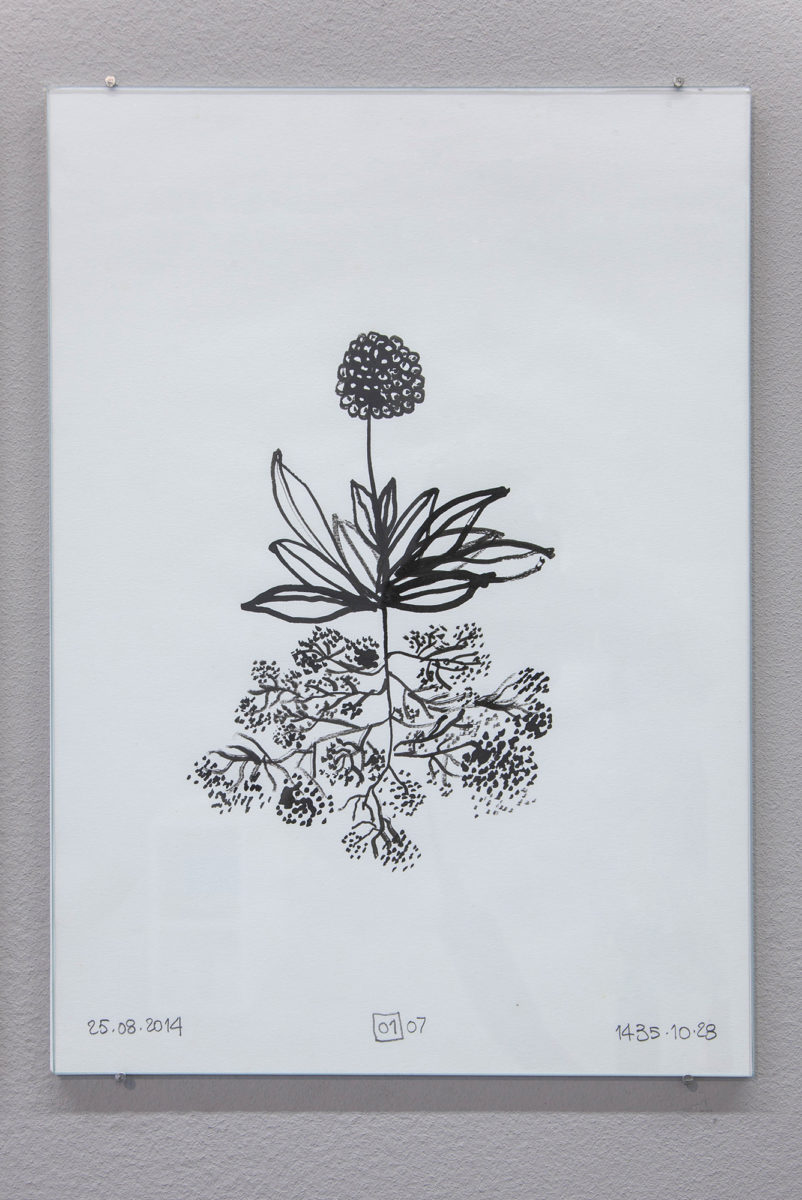

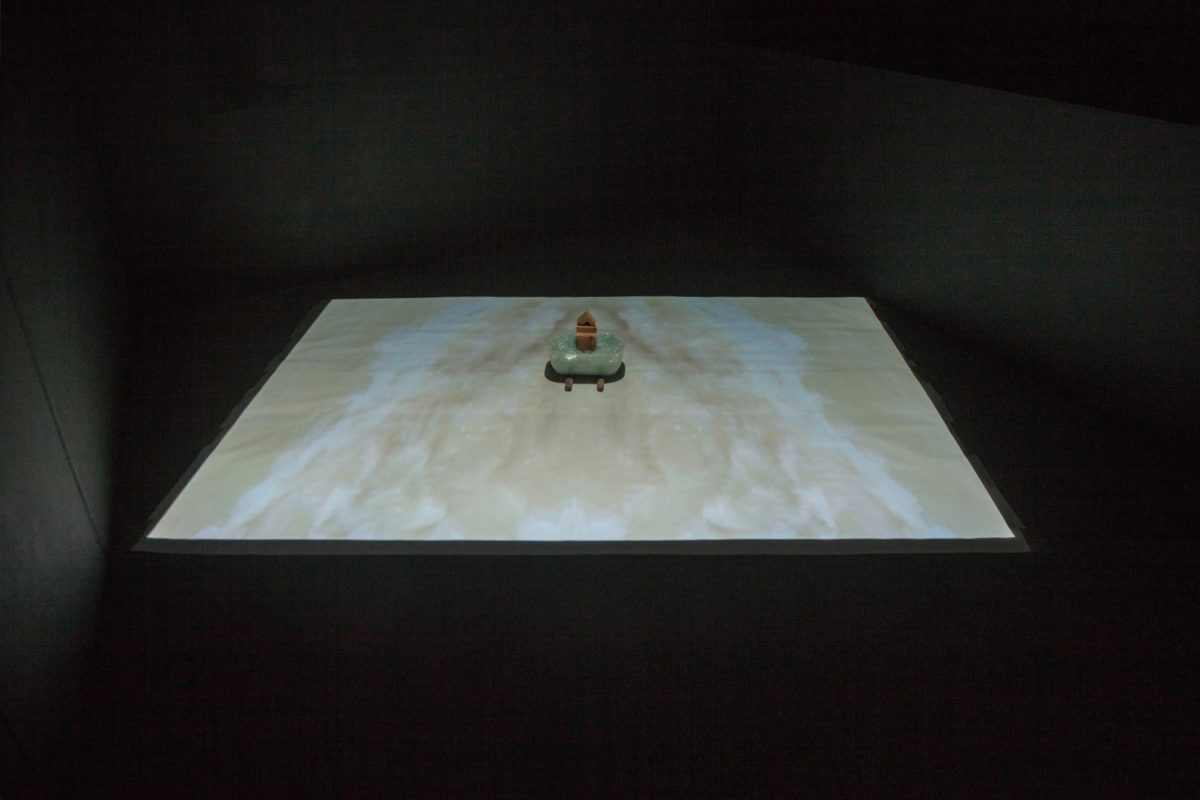

For his new exhibition at the Galerie Imane Farès in Paris, the artist Younès Rahmoun pursues the practice of giving Arabic titles to his compositions. Jabal, Hajar, Turab… Habba, Hijra, Ghorfa… Mawja, Markib, Manzil. Mountain, Stone, Dust… Seed, Migration, Room… Wave, Boat, House. Deliberately omitting the article for these titles creates lexical ambiguity1.

Nevertheless, it is tempting to interpret them from a religious perspective, as the Moroccan artist’s assertion of his faith is unique in the history of modern or contemporary artists in the Arab world, and as these words are present in the scriptural sources of Islam. “Hijra” is the Hegira, “Emigration” of the Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina, in 622, and the beginning of the Islamic lunar calendar. But “Hijra” is also the “emigration” (with a small ‘e’) of ordinary men, or “migration” of other elements in Nature, which the artist invokes more widely with the following:

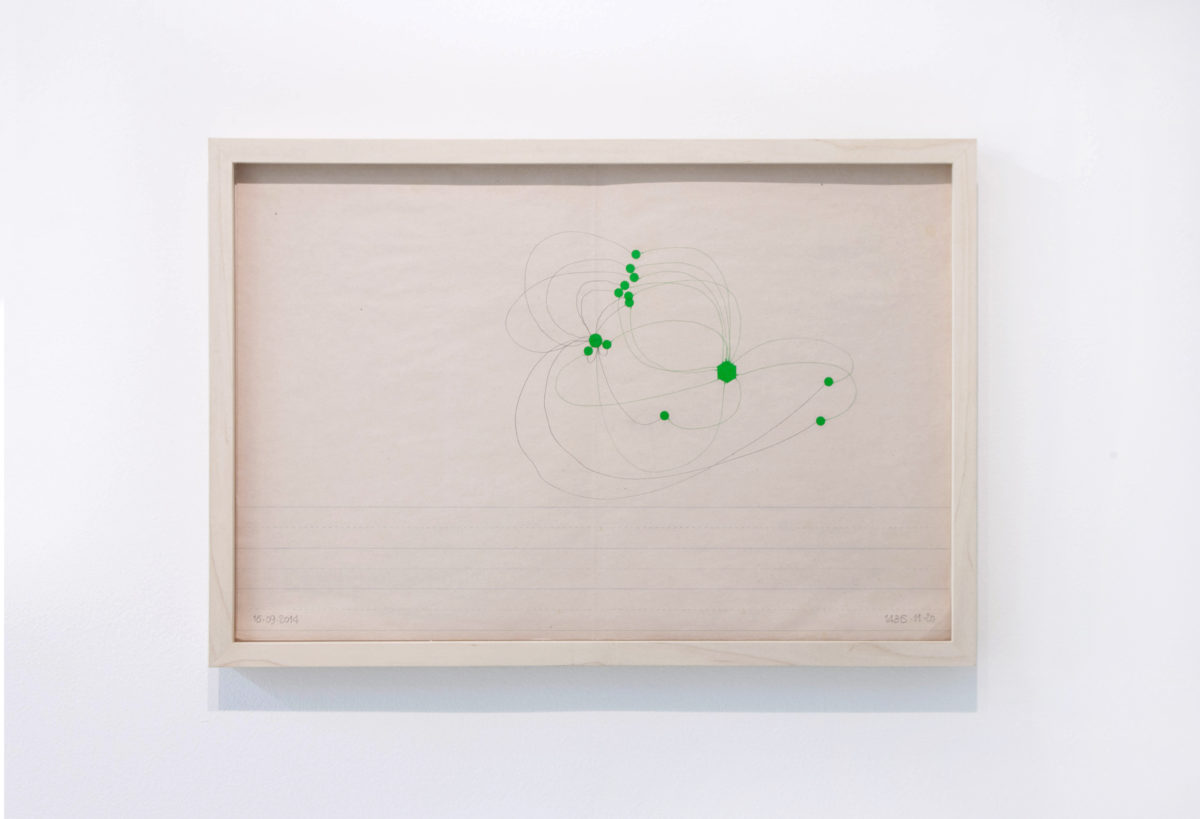

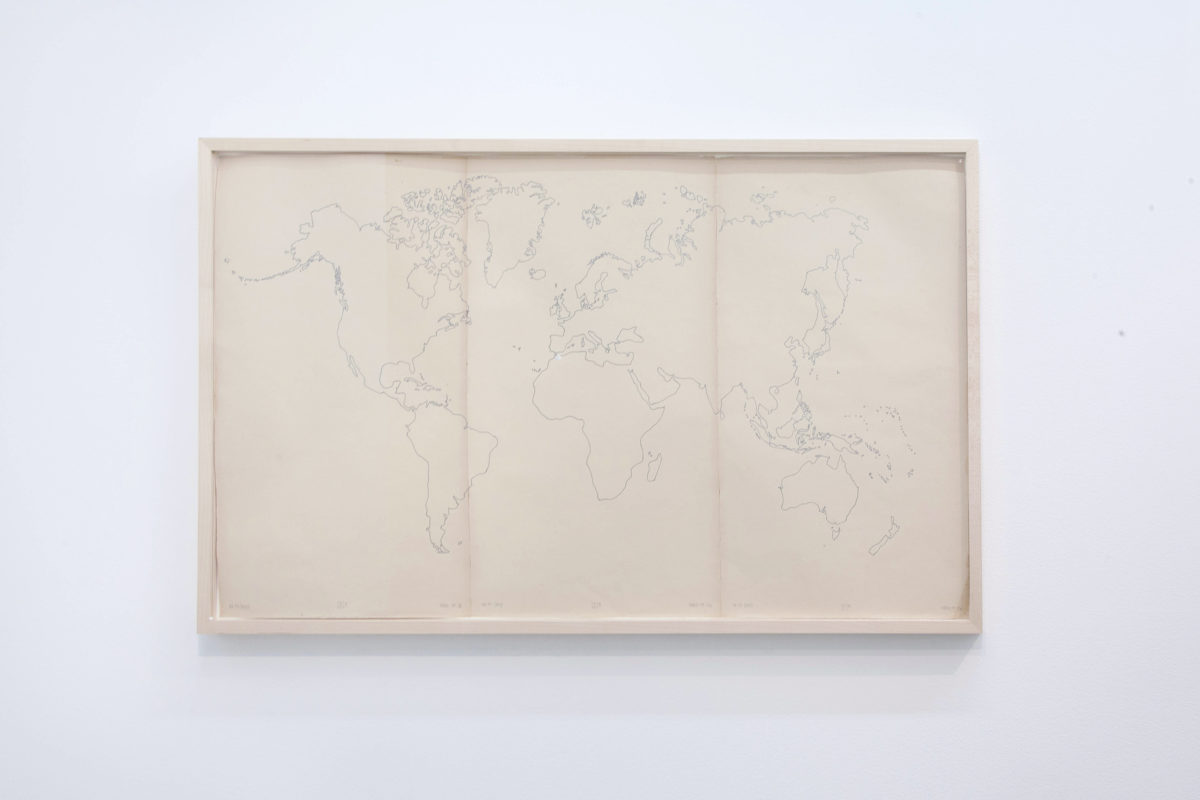

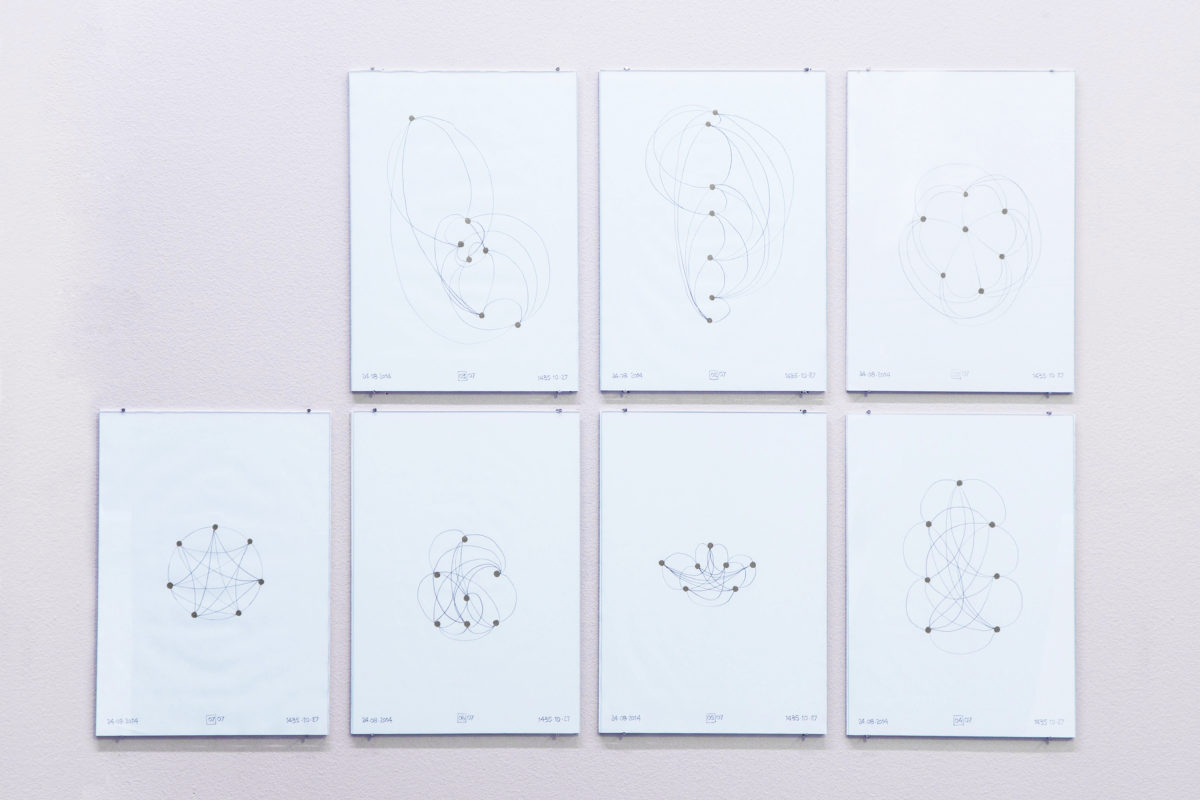

“I have three uncles from the maternal side of my family who live and work in Spain. (…) I know their concerns very well, and I wanted to talk about it indirectly through what I do. In Hijra, I speak of them. I speak of Africans, Syrians, current events, but also and more generally of the displacement of the elements in the universe. (…) For me, whether it concerns slaves [of the Trade Triangle], Riffians who went to Europe to earn a living, or the prophet Muhammad, it all makes sense, like the planets moving in the universe, or atoms moving at their own scale. And human beings, animals, seeds that travel and give life. Insects, wind and water; everything is in perpetual motion, including the mountains too.” In keeping with the theme of perpetual movement, the artist’s journeys between Africa, Europe and Asia are also documented in this exhibition.

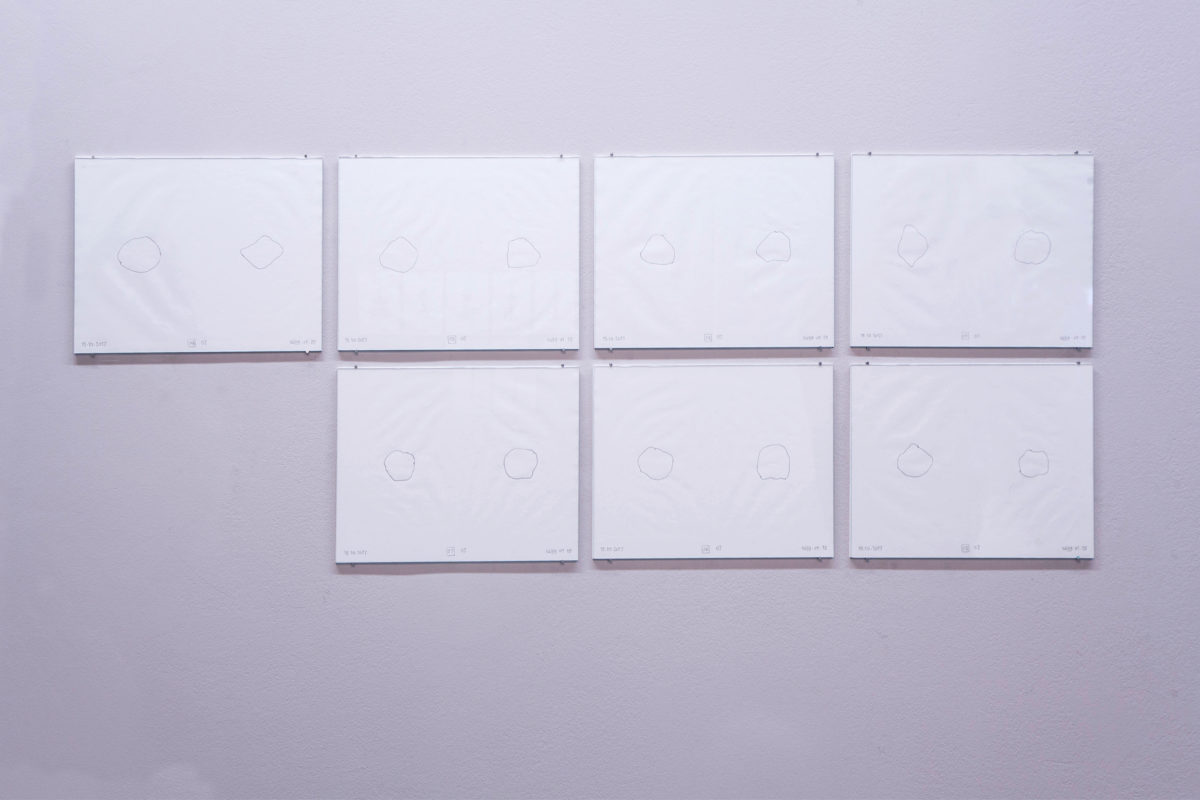

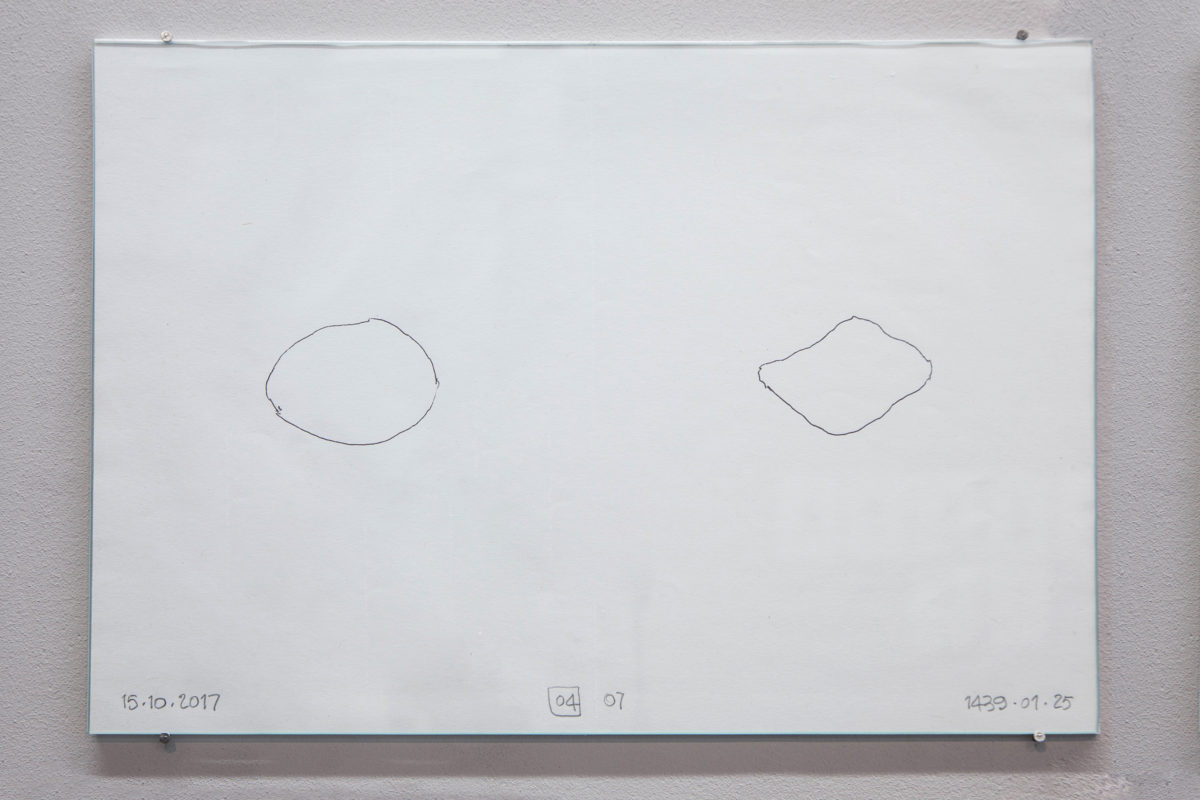

From performances to installations, Younès Rahmoun has since 2007 played with reproducing the room as a space “of work, exhibition and meditation”. Initially between 1998 and 2005, and since 2010, he has worked on the substitution, collection and combination of stones which map the irreversible yet delicate imprint of his passage on Earth, from the Maghreb to Mashrek, from France to China. Set against the heavy footprint of industrial revolution, and far detached from its infinite, mad rush, the artist’s unusual yet worthwhile quest seems to consist in finding the right scale for the human body.

“My religion, my faith is one source of inspiration for me. It’s very important for sure. But in my work what I really want to reveal is the human, and its scale in relation to the universe.”

Ghorfa has the dimensions of a seated body; and when the seven stones exchanged from Hijra are gathered in the palms of its hands, they measure the size of a human heart.

— Alexandre Kazerouni, Paris, January 2018

1. This text is based on two interviews recorded with the artist on December 24th and 25th, 2017.