Sammy Baloji

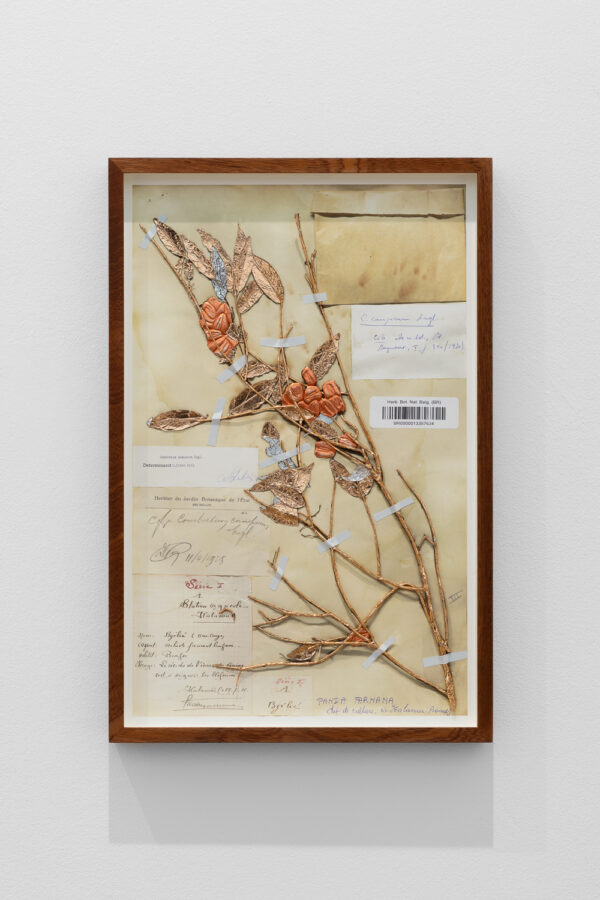

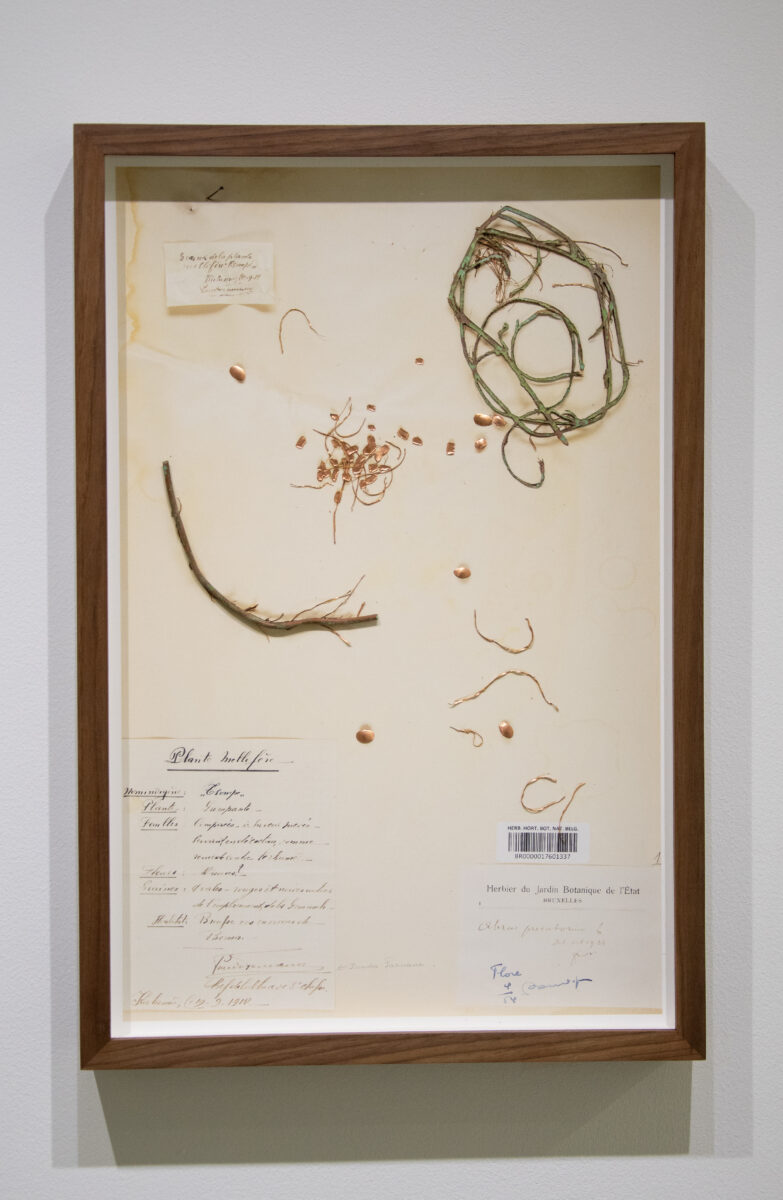

Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[+]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[-]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[+]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[-]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[+]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[-]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[+]Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

[-]343 cm x 461 cm, Wool, cotton, and linen

[+]343 cm x 461 cm, Wool, cotton, and linen

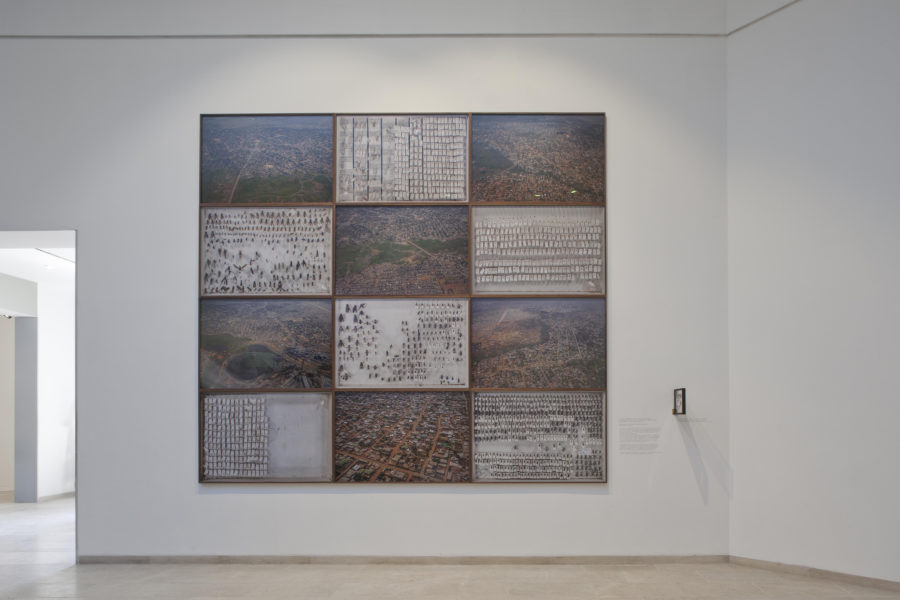

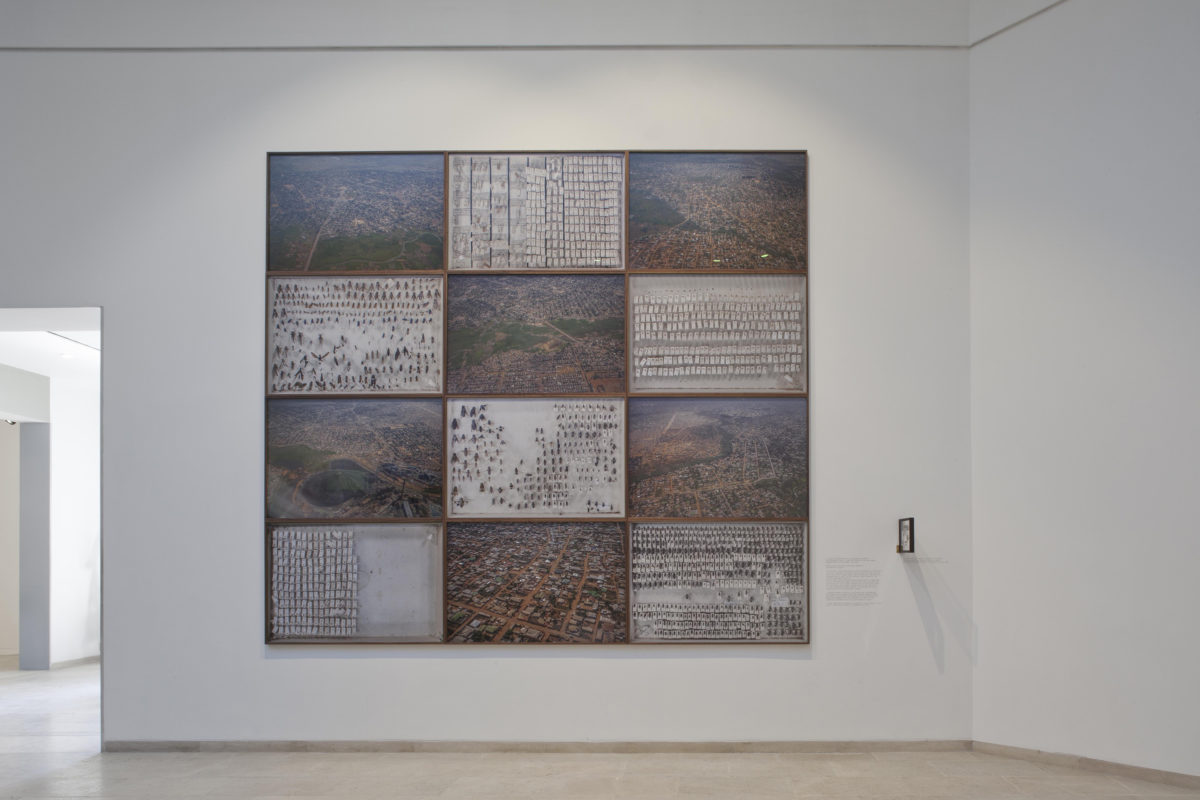

[-]Installation of prints on prepared paper

62,4 x 62,4 cm (each)

Each framed photograph is an edition of 5 + 1AP

Installation of prints on prepared paper

62,4 x 62,4 cm (each)

Each framed photograph is an edition of 5 + 1AP

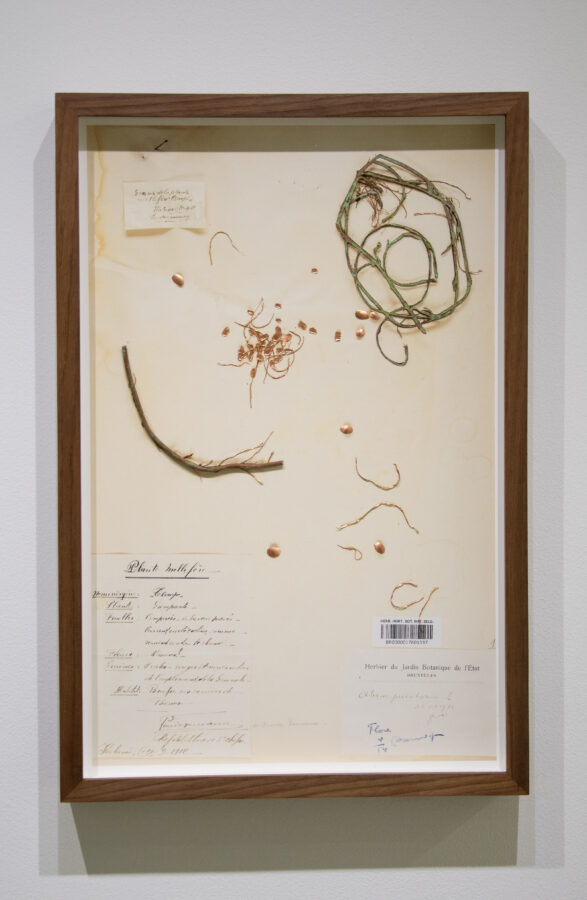

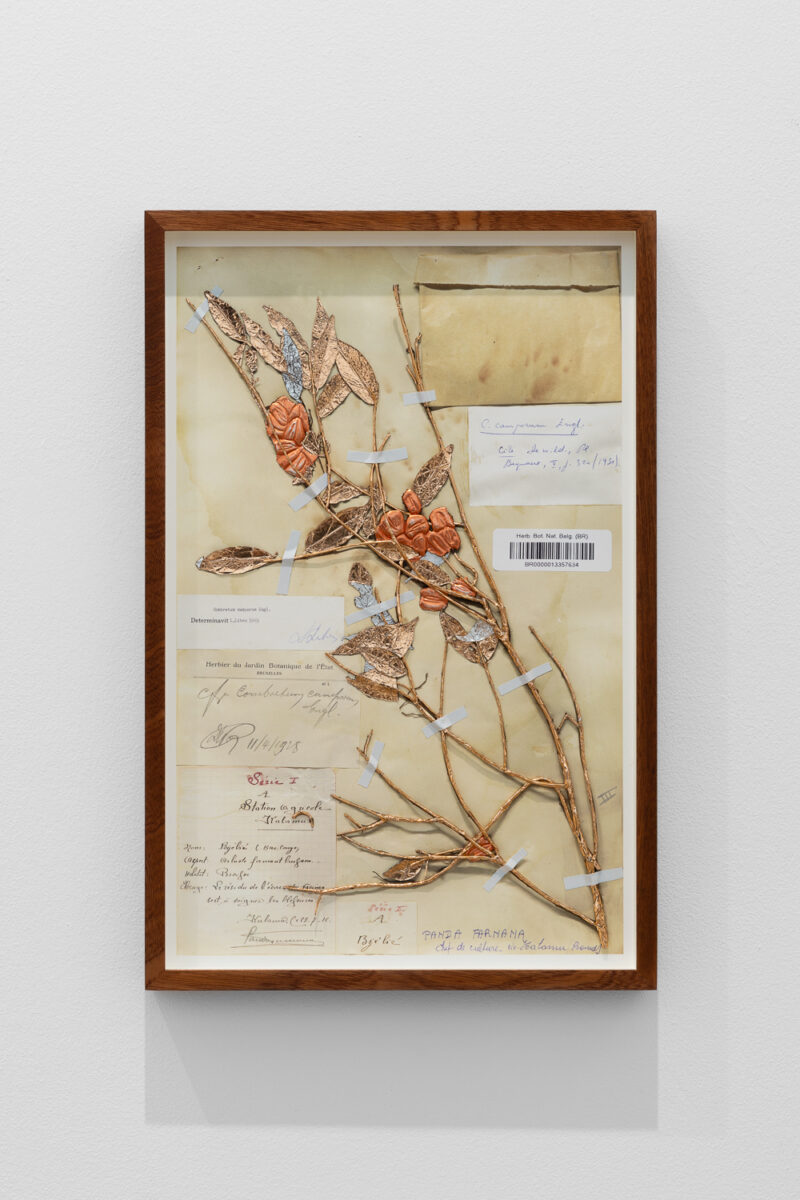

Metal wire and copper foil sculpture; print glued on Dibond,

framed

44,5 x 28,7

Unique

Metal wire and copper foil sculpture; print glued on Dibond,

framed

44,5 x 28,7

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

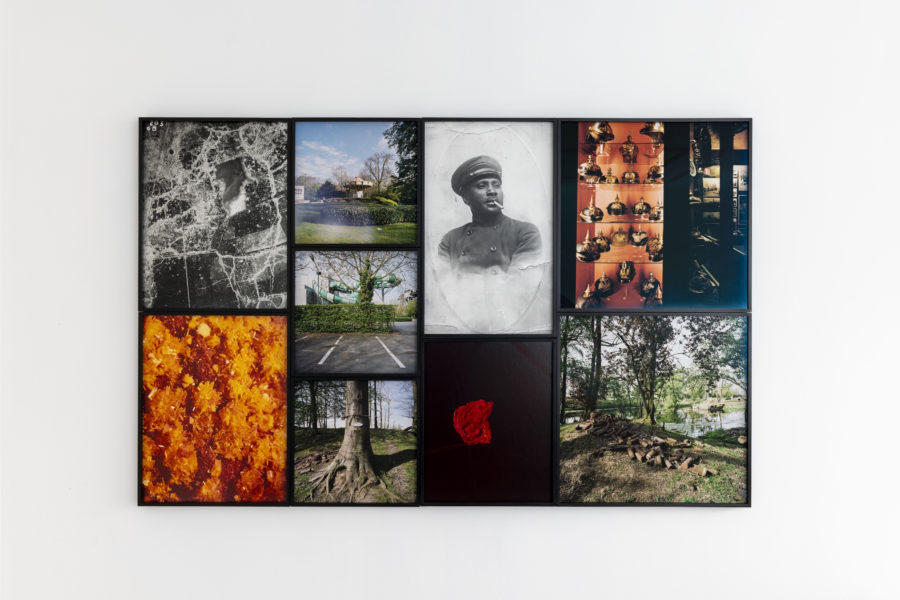

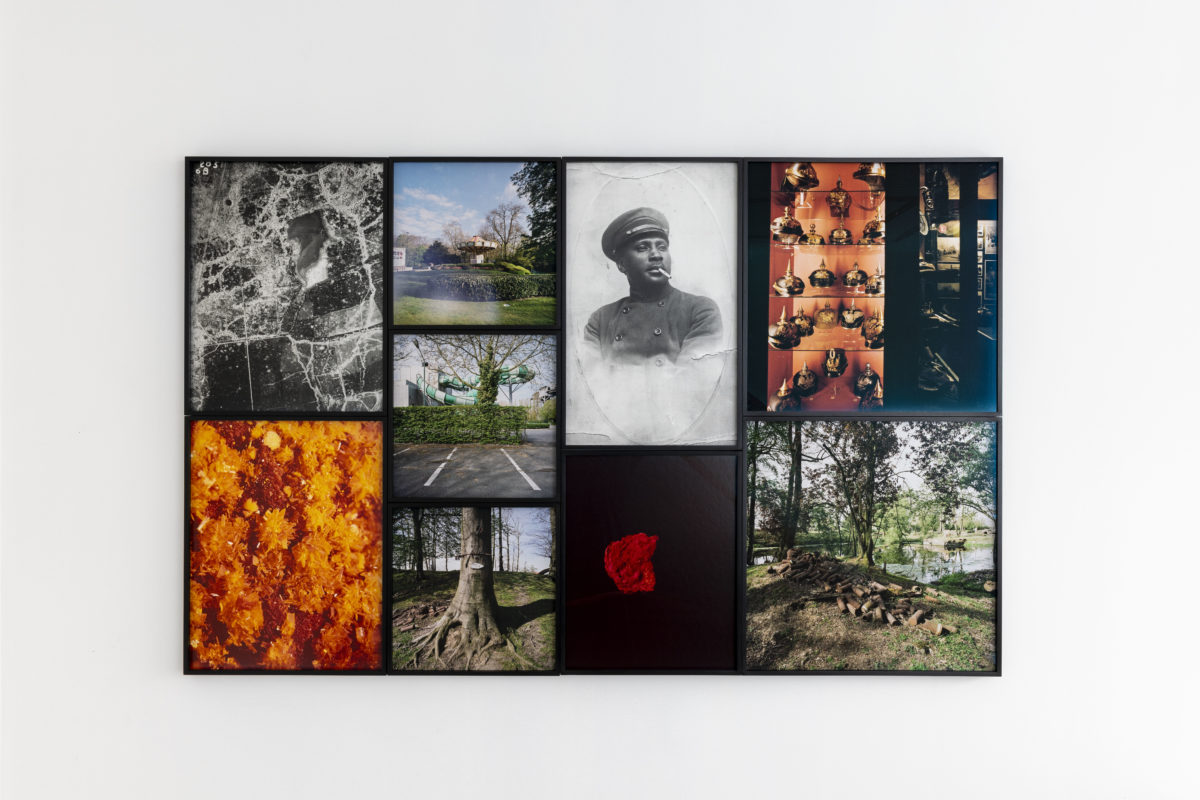

9 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

199,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

9 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

199,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

6 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

97,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

6 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

97,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

10 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

186,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

10 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

186,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

Video, sound, colour

21’04’’

Ed de 5 + 1 AP

Edition disponible: 1/5

Video, sound, colour

21’04’’

Ed de 5 + 1 AP

Edition disponible: 1/5

The installation includes:

-The Extracted Pavilion: the model on a special plinth

-Panorama Atmosphérique, 1935; Drawing, 1935; L’illustration Congolaise nr. 146, 1933: 3 framed archive images

-Defining Comfort and Designing Comfort: 2 displays containing a selection of books and archives (200 x 50 x 120 cm each)

-Aequare.The Future that never was: video, sound, colour, 21’04’’ (edition 1/5)

Ed of 5 + 1 AP (edition 1/5)

Variable dimensions

Unique

The installation includes:

-The Extracted Pavilion: the model on a special plinth

-Panorama Atmosphérique, 1935; Drawing, 1935; L’illustration Congolaise nr. 146, 1933: 3 framed archive images

-Defining Comfort and Designing Comfort: 2 displays containing a selection of books and archives (200 x 50 x 120 cm each)

-Aequare.The Future that never was: video, sound, colour, 21’04’’ (edition 1/5)

Ed of 5 + 1 AP (edition 1/5)

Variable dimensions

Unique

Vidéo HD, couleur, son, 10 min 47 sec

[+]Vidéo HD, couleur, son, 10 min 47 sec

[-]Photo © Uffizi, Florence

[+]Photo © Uffizi, Florence

[-]Photo © Beaufort 21

[+]Photo © Beaufort 21

[-]Installation view: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, 2021. Photo © Birger Stichelbau

[+]Installation view: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, 2021. Photo © Birger Stichelbau

[-]Bronze; 52.5 x 51.3 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 52.5 x 51.3 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 64.5 x 63 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 64.5 x 63 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 62 x 50.3 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 62 x 50.3 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

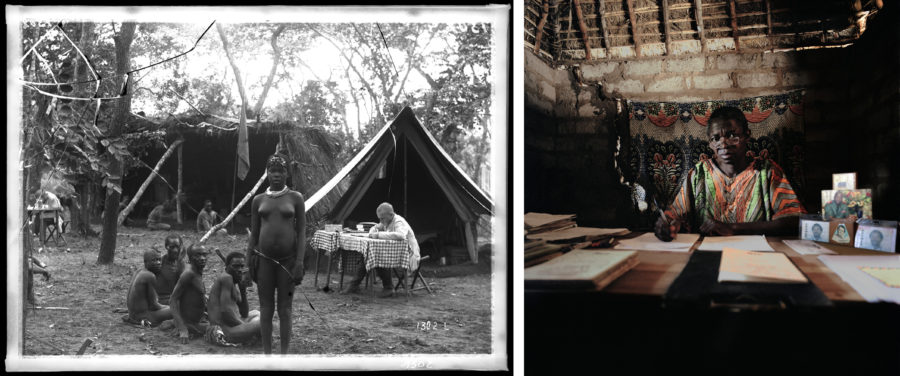

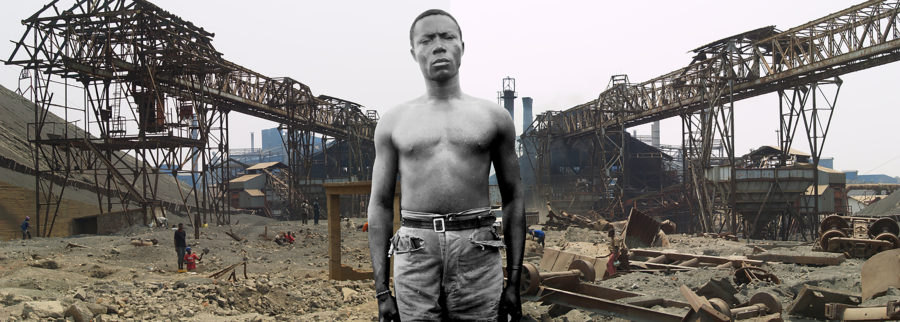

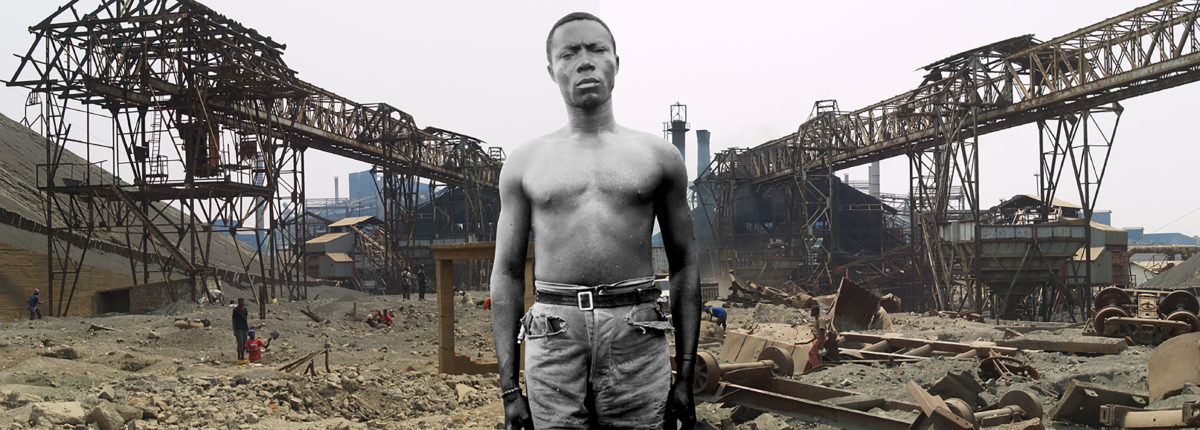

From the series Mémoire (2004-2006)

Archival digital photograph on satin matte paper ; 60 x 160 cm

Edition of 10 + 1 AP

From the series Mémoire (2004-2006)

Archival digital photograph on satin matte paper ; 60 x 160 cm

Edition of 10 + 1 AP

Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

Copper sculpture; print glued on Dibond 28.7 x 44.5 cm Unique

343 cm x 461 cm, Wool, cotton, and linen

Installation of prints on prepared paper

62,4 x 62,4 cm (each)

Each framed photograph is an edition of 5 + 1AP

Metal wire and copper foil sculpture; print glued on Dibond,

framed

44,5 x 28,7

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

Engrave wooden frames with prints glued on dibond

150 x 150 cm

Unique

9 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

199,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

6 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

97,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

10 framed photographs

Negatives 6/6 on matte Photo Rag 308gr paper

Prints on hannemuhle baryta metalic 315gr

Prints on hannemuhle baryta 315gr

186,5 x 120 x 4,5 cm

Edition of 3

Video, sound, colour

21’04’’

Ed de 5 + 1 AP

Edition disponible: 1/5

The installation includes:

-The Extracted Pavilion: the model on a special plinth

-Panorama Atmosphérique, 1935; Drawing, 1935; L’illustration Congolaise nr. 146, 1933: 3 framed archive images

-Defining Comfort and Designing Comfort: 2 displays containing a selection of books and archives (200 x 50 x 120 cm each)

-Aequare.The Future that never was: video, sound, colour, 21’04’’ (edition 1/5)

Ed of 5 + 1 AP (edition 1/5)

Variable dimensions

Unique

Vidéo HD, couleur, son, 10 min 47 sec

Photo © Uffizi, Florence

Photo © Beaufort 21

Installation view: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, 2021. Photo © Birger Stichelbau

Bronze; 52.5 x 51.3 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 64.5 x 63 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

Bronze; 62 x 50.3 x 2 cm; edition of 3 + 1 AP

Photo © Orfée Grandhomme

From the series Mémoire (2004-2006)

Archival digital photograph on satin matte paper ; 60 x 160 cm

Edition of 10 + 1 AP

The Crossing, 2022

Woven wool, 88 meters long, made in collaboration with Traumnovelle

Gnosis, 2022

Site-specific installation including maps printed on forex (images courtesy of Afriterra) and fiberglass globe, made in collaboration with Traumnovelle

Goods Trades Roots, 2020

Weaving loom in Afzelia wood, Weaving in copper acrylic and cotton yarns; inspiry by a ‘M’fuba’ mat made of fibre of screw pine from the Vili culture (Kongo), in the collections of the Anthropology Dept. of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian. Collected by Carl Steckelmann in 1892. Inv. No. 165321; made in collaboration with Estelle Chatelain

Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues, 2017 – … Copper Negative of Luxury Cloth Kongo Peoples; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo or Angola, Seventeeth-Eighteenth Century

Bronze

The original cushion cover made in raffia, first inventoried 1737, is kept at the Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen

Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues, 2017 – … Copper Negative of Luxury Cloth Kongo Peoples; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo or Angola, Seventeeth-Eighteenth Century

Bronze

The original cushion cover made in raffia, first inventoried 1709, is kept at Polo Museale di Lazio, Museo Preisteorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini, Rome

Exhibition views © Uffizi, Florence

K(C)ongo Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues: Subversive Classifications is an exhibition conceived specifically for the Andito degli Angiolini as a new and extended chapter of Sammy Baloji’s ongoing reflection on and dialogue with a series of artefacts and archives dating back to the Kingdom of Kongo and that had arrived in Europe between the 16th and 17th centuries.

Central to the exhibition is a set of four oliphants –carved ivory war trumpets—, three of which are part of the collection of the Tesoro dei Granduchi at Palazzo Pitti, and one of which belongs to the Museo delle Civiltà di Roma. Intricately related to the history of 16th century Florence and that of Cosimo I de’ Medici, these impressive artefacts form the conceptual and aesthetical inspiration for Baloji’s project, paving the way for his complex artistic research that highlights the interlacing of historical moments and objects. Similarly, the Kongo textiles form another anchor point in this exhibition: they are coeval to the oliphants, arriving in Italy through Portuguese merchants and later sold to aristocratic connoisseurs. Baloji’s exhibition aims to excavate these pre-modern relationships and the horizontal exchanges between Africa and Europe that developed during and after this period, as evidenced by the letters from King Afonso I of Kongo to the Portuguese king Manuel I, also displayed here.

Marked with motifs inspired by those decorating the oliphants, The Crossing is an elaborate 88 meters long wool carpet that guides the visitor throughout these “interlaced dialogues” which form the basis of the exhibition. The copper and bronze wall-sculptures from the series Negative of Luxury Cloth and the weaving loom titled Goods Trades Roots are also marked by geometric patterns, recalling the precious raffia textiles that arrived in Italy through Portuguese merchants between the 16th and 17th centuries.

Inspired by Cosimo’s Hall of Geographical Maps at Palazzo Vecchio, the immersive installation Gnosis further explores the concept of the Wunderkammer, of which many objects came from future colonies. Similarly, the sculptures displayed on the Uffizi storagerack were collected in the Congo while it was a Belgian colony, before being acquired by the Museo di antropologia e etnologia dell’Università di Firenze at the beginning of the 20th c., and later exhibited at the Scultura Negra exhibition of the XIII Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia in 1922.

Baloji thereby contextualizes these Renaissance collections of mirabilia and naturalia and the emergence of modern anthropological and ethnographic museums in Italy. The classification systems of these museums revealed the exoticized and racialized perspective through which the African continent was presented in the age of empires as underlined by philosopher V. Y. Mudimbe in his seminal book The Invention of Africa (1988).

The exhibition highlights a “subversive” facet of the historical accounts around Kongo artefacts. In line with contemporary cultural perception and values, Baloji’s research goes beyond modern exoticizing and ethnographic classifications which can be considered as consequences of both the transatlantic slave trade and the Scramble for Africa of the late 19th century.

…and to those North Sea waves whispering sunken stories (I), 2021

Metal and glass terrarium containing various tropical plants, potting soil, clay pebbles

223,8 x 230 x 129,6 cm approx.

Unique

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at Beaufort 21, Zeebrugge

…and to those North Sea waves whispering sunken stories (II), 2021

Metal and glass terrarium containing various tropical plants, potting soil, clay pebbles, and sound

230 x 273 x 307 cm

Unique

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, 2021. Photos © Birger Stichelbau

Part. I. Beaufort Triennale, Zeebrugge, 2021

Only a few kilometers from the dike in Knokke-Heist is the sea bank ‘de Paardenmarkt’. After the First World War, no less than 35,000 tons of German ammunition were dumped at this site, leading to a particularly precarious situation since the invisible munition dump will slowly become a toxic threat to underwater ecosystems. The little-known dumping operation can be seen as a striking analogy with the role of the Democratic Republic of Congo during WWI.

As a colonial power, Belgium decided to deploy only a few Congolese soldiers on the European front, but led larger troops in the Congo. Historical accounts of the Great War never say a word about these colonial troops. Just like the ammunition dump, official monuments or ceremonies simply obscure their presence completely. Seeking to complete this history, artist Sammy Baloji found the biography of Albert Kudjabo, one of the thirty-two Congolese men who fought in Europe during WWI. Kudjabo was captured by the German army, and was “studied”, seen merely as a “scientific phenomenon” because he was black. Baloji found fragments of recordings made by the German military of their examination of Kudjabo. These are the only audio recordings of a soldier from WWI.

All these shadow histories crystallize subtly in Baloji’s sculptures. Indeed, the structure of …and to those North Sea waves whispering sunken stories was inspired by the ‘Wardian case’, a glass transport case that was used to protect exotic plants during maritime shippings from the former colonies to Europe. The sculpture’s shape evokes that of Congolese minerals, while the plants it houses are those exiled from the same country. The temporary protective case has parallels with the temporary protective solution of the sea dump. The work gives a voice back to forgotten traces from the past, but also emphasizes their effects in a global world and the active attempts at making things forgotten.

—Lucrezia Cippitelli

Part. II. In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres

As part of his residency at the Flanders Fields Museum, Sammy Baloji explores the subtle but complex ties between his native Congo and its former coloniser Belgium. Through the prism of the First World War, the artist offers a glimpse of how the colony was not only indispensable to Europe’s war effort, but also to its claims to global dominance, capitalism and impact on the current climate crisis. Central to the installation in the In Flanders Fields Museum is a terrarium with tropical plants. It is a modern version of the ‘Wardian case’ with which live plant material was transported to Europe in the colonial period. These plants, transposed from one cultural context to another, are put into perspective with the Congolese who arrived in Belgium with their masters and who joined the Belgian army at the beginning of the war. One of them was Albert Kudjabo, a Congolese who spent four years in German captivity. We not only see him, but also hear him on a sound recording made by German scientists in March 1917 (courtesy of the Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin).

…and to those North Sea waves whispering sunken stories (I), 2021

Metal and glass terrarium containing various tropical plants, potting soil, clay pebbles

223,8 x 230 x 129,6 cm approx.

Unique

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at Beaufort 21, Zeebrugge

…and to those North Sea waves whispering sunken stories (II), 2021

Metal and glass terrarium containing various tropical plants, potting soil, clay pebbles, and sound

230 x 273 x 307 cm

Unique

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, 2021. Photos © Birger Stichelbau

Part. I. Beaufort Triennale, Zeebrugge, 2021

Only a few kilometers from the dike in Knokke-Heist is the sea bank ‘de Paardenmarkt’. After the First World War, no less than 35,000 tons of German ammunition were dumped at this site, leading to a particularly precarious situation since the invisible munition dump will slowly become a toxic threat to underwater ecosystems. The little-known dumping operation can be seen as a striking analogy with the role of the Democratic Republic of Congo during WWI.

As a colonial power, Belgium decided to deploy only a few Congolese soldiers on the European front, but led larger troops in the Congo. Historical accounts of the Great War never say a word about these colonial troops. Just like the ammunition dump, official monuments or ceremonies simply obscure their presence completely. Seeking to complete this history, artist Sammy Baloji found the biography of Albert Kudjabo, one of the thirty-two Congolese men who fought in Europe during WWI. Kudjabo was captured by the German army, and was “studied”, seen merely as a “scientific phenomenon” because he was black. Baloji found fragments of recordings made by the German military of their examination of Kudjabo. These are the only audio recordings of a soldier from WWI.

All these shadow histories crystallize subtly in Baloji’s sculptures. Indeed, the structure of …and to those North Sea waves whispering sunken stories was inspired by the ‘Wardian case’, a glass transport case that was used to protect exotic plants during maritime shippings from the former colonies to Europe. The sculpture’s shape evokes that of Congolese minerals, while the plants it houses are those exiled from the same country. The temporary protective case has parallels with the temporary protective solution of the sea dump. The work gives a voice back to forgotten traces from the past, but also emphasizes their effects in a global world and the active attempts at making things forgotten.

—Lucrezia Cippitelli

Part. II. In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres

As part of his residency at the Flanders Fields Museum, Sammy Baloji explores the subtle but complex ties between his native Congo and its former coloniser Belgium. Through the prism of the First World War, the artist offers a glimpse of how the colony was not only indispensable to Europe’s war effort, but also to its claims to global dominance, capitalism and impact on the current climate crisis. Central to the installation in the In Flanders Fields Museum is a terrarium with tropical plants. It is a modern version of the ‘Wardian case’ with which live plant material was transported to Europe in the colonial period. These plants, transposed from one cultural context to another, are put into perspective with the Congolese who arrived in Belgium with their masters and who joined the Belgian army at the beginning of the war. One of them was Albert Kudjabo, a Congolese who spent four years in German captivity. We not only see him, but also hear him on a sound recording made by German scientists in March 1917 (courtesy of the Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin).

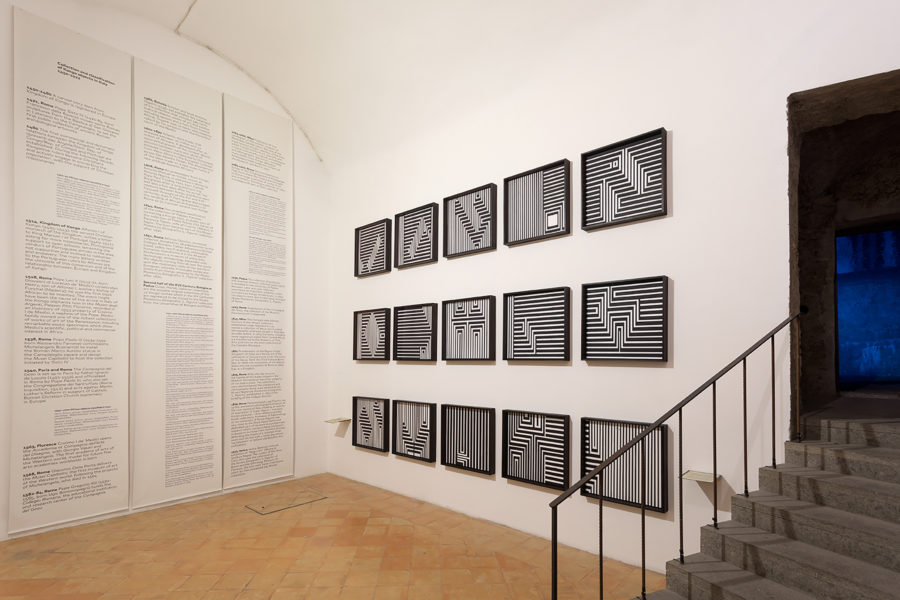

Mfuba’s Extract. Wunderkammer (Work in Progress), 2020

15 framed drawings

80 x 80 x 30 cm (each)

Acrylic paint on paper

Unique

Installation views:

© Daniele Molajoli / Académie de France à Rome – Villa Médicis

Sammy Baloji at Beaux-Arts de Paris, 2021. Photos © Martin Argyroglo

Le projet de recherche de Sammy Baloji à la Villa Médicis explore les échanges politico-religieux et commerciaux qui se sont établis entre le royaume du Kongo, le Portugal et le Vatican à partir du XVIe siècle, échanges qui ont d’ailleurs été largement renforcés par la traite transatlantique des esclaves.

La recherche en Italie s’inscrit dans la continuité du travail exposé à la Documenta 14, Fragments of Interlaced Dialogue, où Baloji tisse déjà une série de récits en associant archives et objets sur la diffusion et la réappropriation des savoirs et les complexités de la construction de la société congolaise profondément marquée par les effets de la colonisation. Ce travail consiste à établir un parallèle entre les objets Kongo arrivés à Rome vers le XVIe siècle par les missionnaires jésuites, et qui sont entrés par la suite dans les collections du Museo delle Civiltà, et, par conséquent, la création de l’histoire de l’art dans une perspective eurocentrique remontant à la Renaissance.

« Ce qui est intéressant, c’est l’évolution du statut de ces objets à travers le temps dans un premier temps, objets de curiosité, ils sont ensuite intégrés aux collections des musées ethnographiques ou de sciences naturelles et acquièrent alors un nouveau statut. En proposant une installation de dessins de type cinétique inspirés des coussins Kongo, je suggère un changement de regard sur ces mêmes objets. »

—Sammy Baloji

Hobé’s Art Nouveau Forest and Its Lines of Color, 2021

Installation of four wood pannels and acrylic paint on canvas

In collaboration with Inès Di Folca, Elena Valtcheva, Orféé Grand-homme & Ismaël Bennani, Jean-Christophe Lanquetin

210 x 300 x 1 cm, 250 x 200 x 1 cm, 210 x 200 x 1 cm, 240 x 280 x 1 cm

Unique

Installation views: Sammy Baloji at Beaux-Arts de Paris, 2021. Photos © Martin Argyroglo

“Academic papers report that not only was Belgian Art Nouveau strongly influenced by Congolese art, but also that it integrated mate-rials (wood, copper, ivory) from the Congo into its creations. Moreover, the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, before its renovation, presented its collections in an Art Nouveau décor that integrated Kongo fabrics into the walls and furniture, to the point that they no longer appeared as such. I question this scenography by reproducing the display in which Kongo patterns are inte-grated, which I reinterpret with the colors used by W.E.B. Du Bois in the diagrams he presented at the “Exposition nègre” during the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris, to evoke the social condition of Black Americans. The idea is to divert the ethnographic reading that one could have had of these works by emphasizing the modern aspect of these ancient practices. ”

—Sammy Baloji

Goods Trades Roots, 2020

Weaving loom in Afzelia wood

Weaving in copper acrylic and cotton yarns

Inspiry by a “M’fuba” mat made of fibre of screw pine from the Vili culture (Kongo), in the collections of the Anthropology Dept. of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian. Collected by Carl Steckelmann in 1892. Inv. No. 165321 Made in collaboration with Estelle Chatelain

195 x 162 x 12 cm

Unique

Installation views: Sammy Baloji at Beaux-Arts de Paris, 2021. Photos © Martin Argyroglo

Johari – Brass Band, 2020

Copper, brass, steel

Photo © Collection Grand Palais, Didier Plowy

At the beginning of the 19th century, France which was weakened by the revolt and the subsequent loss of Santo Domingo, sold its colony of Louisiana to the United States. The French troops left this territory while abandoning their musical instruments on site. The brass instruments were recovered by Afro-American slaves with which they created Brass Bands. The two sculptures of Sammy Baloji, in the shape of a sousaphone and a French horn, are inspired by this telling chapter in colonial history.

The copper reflect patterns of body scarification, echoing traditional Congolese practices eradicated by the colonial presence. The instruments are incorporated into metal structures that evoke the form of ores from Katanga, a Congolese province with a wealth of mineral resources, overexploited by international companies from colonizing countries since 1885.

Johari – Brass Band is a triumphant symbol of Africa’s reappropriation of its own history.

The accidental encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table 1

Memory is like stagnant water in that it can only operate when activated. Such activation is neither factual nor historical. It is triggered by another mechanism, a shock such as the image of the “accidental encounter, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella” proposed by Lautréamont. In the present case, let’s imagine for a moment that the “umbrella” is the colonized person, the “sewing machine” the colonizer, and the “dissecting table” history. Indeed, colonization was this radical fracture that modified the memory mechanism of those who endured it. It is a fracture in the sense that an external memory was superimposed on the original memory. The result of the encounter is that everything, including certainties, becomes muddled because the memories of all the actors involved in this drama have become an intractable jumble. Memory has become a ruin on which all kinds of subjectivities can be projected. There, there is no lost paradise or theory of origins, but only imaginary constructs. And when one embarks on a re-construction effort, as Sammy Baloji does, it is not to build something identical (which is impossible) but to pave a new form of representation. “I think I had the idea of the two sculptures because I needed to question history. How do we represent representation and what mechanisms do we create to speak about it? Is representation merely human morphology? What are its underlying writings, in other words its identity mechanisms?” 2

That is the essential question the artist was faced with when he was about to accomplish a memory act that would represent. As he has said, he understood at once the limits of figuration that are often attached to this type of object and the importance of metaphorization. Come to think of it, it obviously operates on several plans. The first is the material chosen to embody his concepts, i.e. copper and music. Copper has a double meaning. As any musician would confirm, it refers to a category of wind instruments (brass instruments), but it is also a raw material that was exploited for a long time in the Congo by local people who were practically enslaved. The music is that of the brass bands that appeared in New Orleans in the early 19th century and were particularly thriving in the Congo Square neighborhood. “The idea was to find an interesting element that could provide a temporal analysis that would go beyond a mere intervention on the Grand Palais’s empty pedestals. I wanted to refer to the history of these brass bands, which I discovered through the archives of William Shepard, an African American missionary who arrived in the Congo in the 1890s to contribute to the emancipation of his Congolese brothers. But what I found to be even more interesting is that Shepard also created a brass band movement in the Congo, and I found an image of a group of Congolese musicians with drums and saxophones.” 3 We are here at the center of what Pierre Verger called the “ebb and flow” 4 , i.e. the way history goes back and forth and revisits in cycles the meaning of the values and symbols it carries. Baloji would agree with me that the trigger was not so much the discovery of Congo Square, which could represent a fictitious Africa, than this archival image of Congolese people marching with drums and saxophones, thus imprinting on the local culture an external element, which comes back with a boomerang effect. The Kimbanguist Church, to mention the most famous Congolese church, immediately seized this phenomenon that combined aspects of celebration, funeral and military organization.

Unwittingly enacting Jean-Paul Sartre’s thinking, Sammy Baloji has, through a phenomenological shift, given a conscience to an object that would otherwise have appeared trivial. “Image is the way in which an object appears in consciousness, or indeed a certain consciousness gives itself a certain object.” 5 Isn’t it the best definition of history considered in its full subjectivity? Isn’t it an illustration of our unique experience in front of an object that, mixing multiple references, suddenly becomes a polysemy? We cannot reduce history to the obviousness of its manifestation, but to the subjectivity of our gaze, says Sammy Baloji through this public artwork. Baloji’s work is a mise en abyme that combines contradictory discourses. These two “brass”, which upon closer inspection reveal scarifications, are placed in metal cages that refer to the scientific expeditions of the colonial era with their cabinets of curiosities, dreams of universalism, international exhibitions and anthropological and botanical “discoveries”. Placed on the stands of a “palace” (le Grand Palais) that was built for the 1897 Universal Exhibition, these works mock the setting in which they are displayed. This pavilion, which in a way was erected to defend other territories, tells us that what seems to be obvious always seeks to go beyond its framework and that it is difficult to constrain an object. An object is not limited to its appearance. It tells the story of a history, the story of an accidental encounter and also, as Ernst Bloch wrote, “the last possible self-encounter, in the darkness of the lived and perceived moment, in the absolute question of the We.” 6

Simon Njami, December 2020

1 Lautréamont, Les Chants de Maldoror [1868]

2 Sammy Baloji during the conference “Des sculptures publiques pour qui ? Pour quoi ?” (Public sculptures for whom? For what?) organized by the Grand Palais, moderated by Chris Dercon, with Yves Le Fur, Simon Njami and Dominique Taffin, 7 December 2020, YouTube

3 Sammy Baloji during the conference “Des sculptures publiques pour qui ? Pour quoi ?” (Public sculptures for whom? For what?) organized by the Grand Palais, moderated by Chris Dercon, with Yves Le Fur, Simon Njami and Dominique Taffin, 7 December 2020, YouTube

4 Pierre Verger, Trade relations between the Bight of Benin and Bahia from the 17th to 19th century, [1968]

5 Jean-Paul Sartre, The Imaginary [1948]

6 Ernst Bloch, The Spirit of Utopia, [1923] (Note: the translation from French is ours)

Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues, 2016 – ongoing

With five bronze:

Copper Negative of Luxury Cloth, Kongo People, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo or Angola, Seventeen-Eighteen Century

2017-2021

Variable dimensions

Editions 3 + 1 AP

Exhibition views:

Other Tales, Lunds Konsthall, 2020. Photos © Daniel Zachrisson

Sammy Baloji at Neue Galerie, Kassel/documenta 14. Photos © Mathias Voelzke

Sammy Baloji, Beaux-Arts de Paris, 2021. Photos © Martin Argyroglo

“Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues (2016 – ongoing) is a a research project that Baloji started in 2015, inspired by the exhibition ‘Kongo: Power and Majesty’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (September 2015 – January 2016). This incredibly well researched exhibition brought together, for the first time, many artefacts originating from the Kingdom of Kongo, most of them usually scattered across European museums and various ethnographic collections, disconnected from the complexity of their origins.

The Kingdom of Kongo (1390–1914) was a territory corresponding to today’s northern Angola, the western part of DRC, the Republic of the Congo and the southernmost part of Gabon. This kingdom entered into contact with the Portuguese in 1483, when the navigator Diogo Cão landed at the mouth of the Kongo river in search of trading opportunities.

Since then and until the period of colonisation in the nineteenth century, there was an intense exchange of precious objects between Kongo and European powers, often travelling as diplomatic gifts between equal regents.5 The most popular objects were oliphants (carved ivory hunter horns) and textiles (cushions and carpets) made from the fibres of the raffia palm. These were all decorated with designs consisting of geometric friezes. These started to appear in many European syncretic artistic productions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which demonstrates the stylistic influences between the two continents.

Interestingly, after the Kingdom of Kongo was converted into Christianity the first bishop from sub-Saharan Africa, appointed by Pope Leo X (an uncle of Cosimo I Medici) in 1518, was Henrique, the son of King Afonso of Kongo. Most probably, the ivory oliphant today in the Medici collection at Palazzo Pitti in Florence was a gift in homage to the family of the head of the Catholic Church, sent by Afonso through the Portuguese.

Among the many objects on show at the Met – testifying to power relations radically different from those of exploitation and slavery in the better known nineteenth century – there were also some on loan from museums in Sweden and Denmark. One cushion from the Swedish Royal Collections, first recorded in 1670, must have been looted from Emperor Rudolf II’s kunstkammer collection in the Prague Castle when it was sacked by Swedish troops in 1648 and then transferred to Queen Christina.6 The cushions from Nationalmuseet in Copenhagen, probably acquired from Dutch merchants, originally appeared in Denmark in 1650 as part of King Frederik III’s royal kunstkammer and were transferred to the National Museum in 1825.

For his installation at the Neue Galerie in Kassel during Documenta 14 in 2017 Baloji used some of these Danish-owned luxury objects, both physically and conceptually. He took high-resolution photographs of the refined fabrics and used them to create copper negatives, which he exhibited next to the originals. These inauthentic yet newly dignified forms were an attempt to reanimate the submerged technical knowledge of the Kingdom of Kongo.

After the initial success of the Kongo objects at various European courts the underlying expertise was lost, because of colonisation and the brutal enslavement of the local population under Belgian rule. Baloji’s choice to replicate these objects in copper underlines the continuous exploitation of Kongo under different forms throughout history. At the same time he suggests that these geometric threads from the past might prefigure the binary code behind the functioning of electronic components, thus referencing the use of coltan today.

These objects both conceal and reveal the complexity of their history. Baloji usually exhibits them in juxtaposition with different maps of the Katanga region, which is where most of the DRC’s mining activity takes place. In the room, the map printed across the main wall refers to the colonial maps drawn by the Belgians, who removed references to places, villages or indigenous occupants. This act of abstraction revealed their intention to parcel the region for its minerals.

The map is also reminiscent of the lines of demarcation drawn at the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, where the European powers sanctified the so-called scramble for Africa, the invasion and division of African territory. But Baloji’s map also recalls the geometric patterns of the traded luxury objects from the Kingdom of Kongo, long deprived of its context in western museums and abstracted to the status of pure form.

In a kind of counter-point, two final photographic works are shown with this installation. One is a facsimile: Letter from Afonso I of Kongo to Manuel I of Portugal Regarding the Burning of the ‘Great House of Idols’. Written already in the sixteenth century by the first converted king of Kongo to the king of Portugal, to denounce the looting of artefacts, the involvement of the Portuguese in the slave trade and the misbehaviour of their priests, the letter builds a bridge to currently much-debated issues such as the restitution of stolen objects to African countries or the historical roots of European violence towards Africa.

The second photograph was taken by Baloji in the depository of the Institut des Musées Nationaux (Institute of National Museums) in Kinshasa. On its shelves, both funerary pottery in the Kongo tradition and European earthenware are amassed, demonstrating the ramifications of the long-lasting exchange between the two continents. This photograph presents an unordered way of archiving historical objects, as opposed to the classifying Western method, whichcreated a false imaginary of Africa, fuelled by notions of primitive and non-developed cultures. What strikes me about the two extremely different ways of preserving these precious objects is not primarily the indications of different material infrastructures in Western Europe and the Congo, nor indeed the opposed relations to power and its symbols, but rather the acute sense of potential for other tales that the photograph radiates.”

— Matteo Lucchetti, 2020

Negative of Luxury Cloth, Fig. 3, Fig. 84, Fig. 93, 2020

Bronze

52,3 x 51,3 cm; 64,5 x 63 cm; 62 x 50,3 cm respectively

Editions of 3 + 1 AP

Design and production: Orfée Grandhomme & Ismaël Bennani

Modeling: Julien Dutertre, Jean-Daniel Bourgeois

Foundry: Sara de Groeve

“Sammy Baloji’s research project at the Villa Medici explores the political-religious and commercial exchanges that have been established between the Kongo Kingdom, Portugal and the Vatican from the 16th century, exchanges, moreover, largely supported by the transatlantic slave trade. The starting point for this historical and artistic research is the installation Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues presented at documenta14 in Cassel in 2017: in fact, Sammy Baloji was already weaving a series of narratives there, combining archives and objects on the dissemination and re-appropriation of knowledge and the complexities of the construction of Congolese society deeply marked by the effects of colonization. (…)

The transfer of fabrics onto copper plates is a reminder (…) of the economic and political tensions linked to the mass exploitation of copper in Katanga. [The Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues and Negative of Luxury Cloth projects are] therefore, a geographical and historical mapping and testimony of the forced migrations of men and objects, as well as of the unbalanced entanglements that are still part of the social, political and economic relations between Africa and Europe”.

— Lucrezia Cippitello and Estelle Lecaille, in Dans le tourbillon du Tout-monde, Di Virgilio Editore, 2020 [our translation]

Negative of Luxury Cloth, Fig. 3, Fig. 84, Fig. 93, 2020

Bronze

52,3 x 51,3 cm; 64,5 x 63 cm; 62 x 50,3 cm respectively

Editions of 3 + 1 AP

Design and production: Orfée Grandhomme & Ismaël Bennani

Modeling: Julien Dutertre, Jean-Daniel Bourgeois

Foundry: Sara de Groeve

“Sammy Baloji’s research project at the Villa Medici explores the political-religious and commercial exchanges that have been established between the Kongo Kingdom, Portugal and the Vatican from the 16th century, exchanges, moreover, largely supported by the transatlantic slave trade. The starting point for this historical and artistic research is the installation Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues presented at documenta14 in Cassel in 2017: in fact, Sammy Baloji was already weaving a series of narratives there, combining archives and objects on the dissemination and re-appropriation of knowledge and the complexities of the construction of Congolese society deeply marked by the effects of colonization. (…)

The transfer of fabrics onto copper plates is a reminder (…) of the economic and political tensions linked to the mass exploitation of copper in Katanga. [The Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues and Negative of Luxury Cloth projects are] therefore, a geographical and historical mapping and testimony of the forced migrations of men and objects, as well as of the unbalanced entanglements that are still part of the social, political and economic relations between Africa and Europe”.

— Lucrezia Cippitello and Estelle Lecaille, in Dans le tourbillon du Tout-monde, Di Virgilio Editore, 2020 [our translation]

Negative of Luxury Cloth, Fig. 3, Fig. 84, Fig. 93, 2020

Bronze

52,3 x 51,3 cm; 64,5 x 63 cm; 62 x 50,3 cm respectively

Editions of 3 + 1 AP

Design and production: Orfée Grandhomme & Ismaël Bennani

Modeling: Julien Dutertre, Jean-Daniel Bourgeois

Foundry: Sara de Groeve

“Sammy Baloji’s research project at the Villa Medici explores the political-religious and commercial exchanges that have been established between the Kongo Kingdom, Portugal and the Vatican from the 16th century, exchanges, moreover, largely supported by the transatlantic slave trade. The starting point for this historical and artistic research is the installation Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues presented at documenta14 in Cassel in 2017: in fact, Sammy Baloji was already weaving a series of narratives there, combining archives and objects on the dissemination and re-appropriation of knowledge and the complexities of the construction of Congolese society deeply marked by the effects of colonization. (…)

The transfer of fabrics onto copper plates is a reminder (…) of the economic and political tensions linked to the mass exploitation of copper in Katanga. [The Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues and Negative of Luxury Cloth projects are] therefore, a geographical and historical mapping and testimony of the forced migrations of men and objects, as well as of the unbalanced entanglements that are still part of the social, political and economic relations between Africa and Europe”.

— Lucrezia Cippitello and Estelle Lecaille, in Dans le tourbillon du Tout-monde, Di Virgilio Editore, 2020 [our translation]

Kasala, The Slaughterhouse of Dreams or the First Human, Bende’s Error, 2019

Installation includes a hunting horn with scarifications of the coppersmith Guido Clabots in Dinant, Belgium, copper (variable dimensions); mirrors with photos of Hans Himmelheber and X-ray topograms, UV print of glass, brass frame (202 x 85 cm each); a reproduction of an archival photograph from the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren; Kasala, HD video, color, sound, 30 min

Commissioned in 2019 by the Rietberg Museum in Zürich following a residency of the artist for the exhibition Congo as Fiction, the project, reconfigured and expanded with new productions, was subsequently presented at the Sydney Biennale, Imane Farès in Paris and the ARoS Museum in Aarhus, Denmark.

Exhibition views:

© Museum Rietberg Zürich, photo: Rainer Wolfsberger;

22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), Cockatoo Island. Presented at the 22nd Biennale of Sydney with assistance from the Flemish Ministry of Culture. Photograph: Zan Wimberley.

Imane Farès, Paris, 2020. Photos © Tadzio

ARoS, Aarhus, 2021.

In his installation Kasala: The Slaughterhouse of Dreams or the First Human, Bende’s Error, the internationally renowned artist Sammy Baloji addresses Hans Himmelheber by questioning the way the West deals with colonial collections and archives: what happens to objects from Africa that have landed in museums of the global North, robbed of their original cultural context? In how far is it legitimate to expose the secret inner life of power figures? How can objects reclaim their voice? What alternative forms of remembrance are there?

The writer Fiston Mwanza Mujila composed a Luba-style commemorative poem (kasala) for Baloji’s installation in which he not only captures in poetic words the inhumanity of mining practices, but also goes in search of his own roots at the same time.

A Blueprint for Toads and Snakes, 2018

Installation includes Chura na Nyoka (The Toad and the Snake), wood & canvas; Kasaian Paintings: reproduction of a selection of 138 portraits from Father Verbeek’s collection of popular paintings, digital prints on paper; Map of the Native City printed on Ekoplex wood with original writing in red.

Variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at Framer Framed, 2018. Photo © Framer Framed / Eva Broekema

Central to these new pieces is the theatre play Chura na Nyoka (‘The Toad and the Snake’), written by Joseph Kiwele, a Congolese born statesman who later served as minister in the Katanga Region. The play, which holds a metaphorical message of ethnic segregation, was commissioned by the Belgian colonial regime as an ‘educational tool’ for the population. Baloji relates Kiwele’s theatre script to the colonial urban planning of the ‘indigenous city’ of Lubumbashi, which was also structured according to a politics of segregation. Traces of this segregation are still visible today, for example in the shape of the ‘cordon sanitaire’ (sanitary corridor), a buffer zone inscribed in the landscape meant to effectively separate the black and white population. It is also reflected in the street names, which refer to different ethnic populations. In addition, the aftermath of this colonial segregation resonates in Congo’s contemporary society, which is rife with struggles and ethnic tensions, intensified by economic interests. Both are now used as input for the works in Baloji’s work.

Untitled, 2018

41 mortar shells, interior plants

Variable dimensions

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Exhibition views:

Notre Monde Brûle, Palais de Tokyo, 2020. Photos © Aurélien Mole & Marc Domage

Congoville, Middelheim Museum, 2021.

“I am not interested in colonialism as an event of the past, but rather as a continuation of a system. I have been living in Belgium since 2010, and yet I have never seen an exhibition about the two world wars that mention the involvement of Africa and their consequences on the African continent. However, many African workers were forced to produce copper to make bombs. African soldiers died in Tanzania and Rwanda. But everything is still only seen from one point of view. So I’m putting together stories that we usually try to separate.” (Sammy Baloji)

During the two World Wars, the exploitation of copper in the mines of Katanga increased considerably due to the production of shells. The casings of these shells, often engraved by Poilus, can now be bought on many resale websites. They testify to a popular practice in Belgium consisting in using them as decorative objects or as pots of consistani flowers. Here, Sammy Baloji places plants originating from the mining areas of Katanga which are nowadays frequently found in botanical gardens and European shops. This installation marks the return of the material to its territory of origin, while not ignoring the complex, and at first forceful, paths of their circulation. The artist pays homage to the dead and the hidden histories of Africa that continue to haunt the present.

Tales of the Copper Cross Garden, 2017

Installation includes a black and white photograph installed in four trips of wallpaper, a vitrine containing 80 Katanga crosses with varying patination and 13 Katanga coins in 1 and 5 franc denominations

Edition of 2 + 1 AP

Edition 1/2: Collection Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Exhibition views: Traversées, Poitiers, 2019. Photo © Sébastien Laval

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at EMST-National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens/documenta 14. Photo © Stathis Mamalakis

“I highlight the forms that reveal how closely the axes of the colony and the church are linked in their impositions to the local Katanga culture. This is clear from the urban planning of the colonial city of Elizabethville, later Lubumbashi, where the church and the state both occupy the carfax in the heart of the colonial city.

For me, nothing less than the copper crosses held in front of the hearts of the choir children suggest how the mis-sionaries tried to steal their souls while exploiting the local copper resource for the benefit of Europeans.

V.Y. Mudimbe, who has achieved greatness and recognition through the synthesis of indigenous thought and European education, lingers in his autobiography on his stolen childhood, when Belgian Catholics took him from his parents to school, stealing from him the possibility of an alternative education close to his birthright and the identity of his parents…”

— Sammy Baloji

Tales of the Copper Cross Garden, Episode 1, 2017

HD video, colour, sound

42 min 33 sec

Edition of 5 + 1 AP

Created in the framework of documenta 14, Athens

Installation views: A Blueprint for Toads and Snakes by Sammy Baloji at Framer Framed, 2018. © Framer Framed / Eva Broekema

Credits: Direction, Sammy Baloji; Editing, Simon Arazi; Camera, Sammy Baloji, Gulda Ghislain El Magambo Bin Ali and Pascal Maloji; Executive Production, Estelle Lecaille (mòsso); Production, mòsso; with the support of Mu.ZEE Oostende.

Pungulume, 2016

Installation comprises a HD video and a photography Notebook of the Sanga chief Mpala Swanage’s father, containing the list of names of all his predecessors. Fungurume, 2014 ; 80 x 120 cm

Single-channel version: HD video, colour and sound, 16:9, Sanga spoken, English subtitles, 32 min

Three-channel version: HD video, colour and sound, 16:9, Sanga spoken, English subtitles, 29 min

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

The town of Fungurume is situated in the province of Katanga (D.R. Congo) and the hills and mountains surrounding Fungurume form one of the world’s largest copper and cobalt deposits. In pre-colonial times the area was already a major centre in the copper trading network that ran across Central Africa. Today the mountains have become the property of the American Tenke Fungurume Mining consortium (TFM). From 2009 on, TFM’s mining activities have been in full swing, causing the resettlement of thousands of local Sanga inhabitants. Pungulume focuses on Sanga chief Mpala and his court elders while they are rendering the oral history of the Sanga people, against the backdrop of the industrial destruction of the landscape that anchors Sanga memory and identity.

— Filip De Boeck

Pungulume was made in the context of Suturing the City, a collaborative project by Filip De Boeck & Sammy Baloji and exists as a three-channel video installation and as a single-channel video work.

Notebook of the Sanga chief Mpala Swanage’s father, containing the list of names of all his predecessors. Fungurume, 2014

The Tower: a Concrete Utopia, 2015

Installation composed of a HD video, colour and sound, 70 min, and a photography: The Tower, 7th street, Quartier industriel, municipality of Limete. Kinshasa, 2015, 100 x 150 cm

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

One of the first major monuments of Belgian colonial urban architecture is the Forescom tower.

Built in 1946, it is the first skyscraper in Leopoldville and one of the first towers in Central Africa. Pointing towards the sky, it also stands in the direction of the future. It embodied and made tangible the new ideas of possible futures, and as such, the tower was a material translation and emblematic visualization of colonialist ideologies of progress and modernity. The video The Tower: A Concrete Utopia offers a guided tour by the « Doctor », the owner of this remarkable tower located in Limete, one of Kinshasa’s municipalities. Designed and built by the « Doctor », without the help of any pro-fessional architect, the construction, still unfinished to date, began in 2003. In many ways, this postcolonial tower is a contrapuntal commentary on the 1946 Forescom Tower and all that it demonstrated at the time, while also illustrating the different ways in which the colonial heritage continues to be reformulated and reconstituted today.

802. That is where, as you heard, the elephant danced the malinga. The place where they now grow flowers, 2016

Installation includes wallpapers on canvas with patterns of scarifications, 36 hammered photographs, a set of post-war mortar shells, copper ceiling pieces with scarification patterns, a recording of a selected excerpt from Andre Yav’s book Vocabulaire de ville d’Élisabethville.

Variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: 802. That is where, as you heard, the elephant danced the malinga. The place where they now grow flowers, Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, 2016.

Courtesy Tate, London

“Sammy Baloji’s new exhibition at Galerie Imane Farès is not an exhibition but a journey. A journey into time and space. A mise-en-abîme of all the subjects that he has held dear over the last few years. Within this whole concept, we find the artist’s intellectual and artistic questions. How do we, through a work, translate the untranslatable? He has chosen to immerse us in his world in which, contrary to what the title suggests, an elephant would have a hard time dancing. The room that we enter has an art deco touch that is reminiscent of early twentieth century colonial architecture. Much like a bull in a china shop, Baloji takes us to the heart of a brutal history that his gaze manages to sublimate, without losing tension. The wallpaper and ceiling trim derive their patterns from ritual scarifications, while shells transformed into flower pots are an ironic nod to a trend that the Belgian bourgeoisie maintained landing in the colonies. On the walls a reminder (through an aerial photography archive) of mining and the conditions under which those who worked there lived. And then casually placed on the main table, like a book to read by the fire, The Vocabulary of Elizabethville by German anthropologist Johannes Fabian, in which the author collected the testimonies of African ‘‘domestic servants’’, from Lubumbashi of course: we enter into the heart of the matter.

It is the exploitation of man by man; it is these ‘unknown soldiers’, dead in the two European world wars that the artist wants to talk about. And as we approach the second room, the reality of these scarified faces doesn’t only make reference to initiation rites, but metaphorical masks of injury, the scar and this memory that is reflected in the faces. These faces are punctuated by quotations borrowed from W.E. B. Du Bois, the legendary author of The Soul of Black Folks, and tell us of a mute anger, sadness or the duty of remembrance. Throughout this installation, we find the same author’s gaze which confuses time and history, in the sense that he assigns and unmasks them. We leave this strange journey into the troubled night, disturbed, but more aware of the mechanics of history and what colonisation was. Not, yet again, in a claimant and vindictive way, but as a constant, both discreet and moving. By the way, while I think about it: do you dance the Malinga?”

— Simon Njami, 2016

Hunting and Collecting, 2015

Installation includes The Album, a series of photographic collages (40 x 55 cm) and a metal sculpture (400 x 550 cm), and Hunting & Collecting, an artist’s book (32 pages, 37,5 x 31 cm), a photographic print listing North- and South Kivu NGOs (variable dimensions) and archival photographs courtesy American Museum of Natural History, New York, and Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Variable dimensions

Unique

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji at macLYON/Biennale de Lyon 2015. © Blaise Adilon & Dioramas, Palais de Tokyo, 2016

Sammy Baloji’s works have their roots deep in the ongoing upheavals in Democratic Republic of Congo. At the macLYON, Sammy Baloji has erected a monumental structure that recalls the old dioramas in museums of natural history. The artist recently collaborated with Chrispin Mvano, a journalist from North Kivu (a war-ravaged province) on a photo album project. The album in question contains old colonial photos taken by Belgian Commander Henri Pauwels during his expedition to the then Belgian Congo, between 1911 and 1913. Baloji took inspiration from these to collect together new montages of photos taken by Mvano and photographs of his own taken against the backdrop of the town of Goma. There are, furthermore, fifteen images and watercolours, reproductions from the American Museum of Natural History in New York, that retrace the steps of an expedition to the then Belgian Congo by the famous taxidermist Carl Akeley, along with pictures showing the construction of the diorama that housed “The Old Man of Mikeno”, one of the first stuffed gorillas in the world. There is also a thirty-two page book, a plan of Commander Henri Pauwels’s expedition to Africa, drawn by Chrispin Mvano, the map used by Carl Akeley on one of his African expeditions, as well as drawings of mineralogical studies by the Congolese metals and mineral trading company, Gécamines.

Sociétés secrètes, 2015

Scarification on eight bas-relief copper plates

Each 29.7 x 42 cm

Collection Zinsou, Cotonou, Benin

Médailles: Travail et progrès / L’union fait la force / Baudouin, Roi des belges

Three black and white photographs from a private collection, Lubumbashi.

Sammy Baloji, Secte Punga: Report of a Congolese Detective to the Assistant Director of Security of Kivu (Congo).

One hand-written letter, 16 x 20 cm, one black-and-white photo, 12 x 16 cm.

Collection Jean-Pierre Sonck, Brussels

Exhibition views: Personne et les autres, Belgian Pavilion of the 55th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia. Photos: Alessandra Bello

(…) Sociétés secrètes (2015) also references the human body, but in a different manner. The work connects the surveillance activi-ties of the Belgian Colonial Secret Service, the age-old indigenous practice of scarification, and the copper trade. Secret Service spying methods and security measures were meant to prevent local sects or secret societies (identified by scarifications indicating a specific tribe or group) from rebelling against the colonial state or officially sanctioned religions. These native groups practiced early forms of resistance to colonialism and were closely monitored and persecuted. For instance Simon Kimbangu (1887–1951), the religious leader who founded Kimbanguism, was considered a threat to the colonial regime and sentenced to life imprisonment for the emancipatory rhetoric of his sermons, and the Kitwala sect, which denounced all forms of authority and coercive colonial rule, revolted on several occasions. In the 1950s, such movements added impetus to the nationalist cause.

Baloji began Sociétés secrètes with details from a series of photographs of different examples of scarification found in the archives of the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium. From these, he made a series of copper bas-reliefs, highlighting the details of each pattern. Scarification is an important compo-nent of initiation rites and a strong symbol of indigenous identity. Copper, on the other hand, is a profoundly laden material, associated with the thousands of black laborers who mined the ore for the exclusive profit of white colonizers. Congo has enormous copper deposits. It was one of the principal products of colonial exploitation, and it continues to be unfairly exploited by foreign corporations today. Economic exploitation imposed by the West subjugated the local populations and eradicated their identities; Baloji reinscribes identity by way of a material dependent on the labor of black bodies, juxtaposing two politicized readings of the body in two different corporeal cartographies.

— Katerina Gregos

The Other Memorial, 2015

Copper with engraved scarification patterns of different Congolese communities, found in ethnographic archives

400 x 200 x 200 cm

Unique

Coll. Fondation Sindika Dokolo, Luanda

Additional images: Congoville, Middelheim Museum, 2021.

Three months later in Marrakech, after a series of meetings [between Sammy Baolji and Olafur Eliasson] in Berlin and Copenhagen, the partnership seemed to be having an effect. Baloji had winnowed down a range of possibilities he had been considering in late 2014, and embarked on the copper dome that he would show in Venice. The dome was his first installation, and it was very ambitious, constructed from more than 50 copper panels. On each he superimposed the image of a “scarified” body taken from a book he had unearthed during his extensive research of the Congo during the colonial period.

The way he was using scarification — the etching of a pattern on to the body, a practice common in Africa in the first half of the 20th century — was complex. “In my artwork, I often adopt a multilayered approach,” he explained. “In my photocollages, there are several stories with different time frames set in a fictional context that I have created. I have used the same process with the dome.”

Scarification, which was widely used in initiation rites, was a key cultural signifier in African communities, amounting almost to a map of an individual’s identity. The church in Liège, a memorial to the Western dead of the First World War, had been built in the 1930s with copper

brought from Katanga. By building a small-scale replica with copper panels decorated with images of scarified bodies, Baloji was engaging in an act of reclamation, almost a reverse colonization. “There are seven memorials to the Western war dead in Liège,” he said. “This will be an eighth memorial — to the African war dead.” Baloji also showed related work, including another set of copper bas-reliefs using images of scarification, in the Belgian Pavilion at Venice.

Taken together, these works reflect on the power struggle between colonizers and colonized. That struggle was evident even in the ways in which they built their separate districts in Lubumbashi — a subject that fascinates Baloji and underlies much of his thinking. While the Belgian colonizers preferred regimented streets, set well away from the African part of the city for fear of disease, the indigenous population kept to the geometric forms — echoing patterns common in scarification — of traditional villages. A cultural war was being waged between oppressors and oppressed, and half a century after that war ended Baloji is trying to untangle its meanings.

–Stephen Moss, 2016

Urban Now, 2013-2015

Series of 55 photographs

80 x 120 cm / 100 x 150 cm

Editions of 5 + 2 AP

Exhibition views: Sammy Baloji & Filip De Boeck — Urban Now: City Life in Congo, WIELS. Photo © 2016 Sven Laurent – Let me shoot for you

In Urban Now: City Life in Congo, visual artist Sammy Baloji and anthropologist Filip De Boeck use photography and video to explore how people imagine and live in cities and new urban extensions in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In ongoing discussions about the unique nature of the African city, architects, urban planners, sociologists, anthropologists, and demographers devote a lot of attention to the built form and to the city’s material infrastructure. Architecture has become a central issue in reflecting on how to plan, engineer, sanitize, transform, and imagine new urban paradigms for the African city of the future.

Very often these new urban futures manifest themselves in the form of billboards and advertisements. Inspired by urban models from Dubai and other recent urban hotspots, these promotional images are an aesthetic display of modernization as spectacle. Images of gated communities and luxury satellite towns for a (hypothetical) local upper-middle class foster new dreams and hopes, even as the cities they propose invariably give rise to new geographies of exclusion. In sharp contrast with these neoliberal re-codings of earlier colonialist modernities, the current infrastructure of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is of a different kind. The built colonial legacy has largely fallen into disrepair. Failing material infrastructures and an economy of scarcity now physically delineate the limits of the possible. At the same time, they also generate other possibilities that allow urban residents to create new social spaces that bypass and overcome breakdown and exclusion.

This series reflects on these diverse narratives of urban place-making. Underlying much of Baloji’s and De Boeck’s exploration is the metaphor of the “hole” (“libulu” in Lingala, the lingua franca in large parts of Congo). They investigate the physical and social gaps that exist in Kinshasa and beyond, and explore where and how people transform them into openings for new kinds of creativity, interactivity, and conviviality.

The Album or Pauwel’s Album, 2013-2014

20 Digital archival photographs on Hahnemühle PhotoRag 308 gr

40 x 55 cm (each)

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

Exhibition views: Mu.ZEE, Kunstmuseum aan Zee, 2014; macLYON/Biennale de Lyon 2015. Photo © Blaise Adilon; Dioramas, Palais de Tokyo, 2016

Essay on Urban Planning, 2013

Installation includes twelve framed Inkjet prints on Innova Ultra Smooth Gloss 285 gr (each: 80 x 120 cm, full: 320 x 360 cm), an archival photo displayed between two glass plates in a wall frame perpendicular to the wall, 28 x 28 cm and an extract from the article “L’Urbanisme au Katanga”, in Essor du Congo, special edition for the international exhibition of Elisabethville, 1931, handwritten on the wall

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

Photo : Alessandra Bello

“The neutral zone avoids close contact between whites and blacks. An almost empty area measuring a minimum of 500 meters separates their two areas of settlement, this distance corresponding to that which a malaria-carrying mosquito will normally cover. The neutral zone thus divides the lives of blacks from those of whites: it keeps the latter safe from the sources of malaria, and from the rowdy activities of blacks, so creating completely independent living conditions for each race … it is a true cordon sanitaire, placed at a right angle from the prevailing winds … our urban planning contents itself with creating developments that satisfy conditions of hygiene, salubrity and security, giving the white and black races the opportunity to live according to the hopes and needs of each, however modest these might be.”

Hins, R., “L’Urbanisme au Katanga” [Urban Planning in Katanga], in the special issue of Essor du Congo [Development in Congo] published on the occasion of the International Exhibition of Elisabethville, 1931 (non paginated). Extract from the article: “Fissures dans le ‘cordon sanitaire’. Architecture hospitalière et ségrégation urbaine à Lubumbashi, 1920-1960”, [Problems in the ‘sanitary cordon’. Hospital Architecture and Urban Segregation in Lubumbashi, 1920-1960] by Johan Lagae, Sofie Boonen & Maarten Liefooghe from the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning of Ghent University.

Kolwezi, 2010-2012

Series of 53 photographs

Digital inkjet prints on Baryta paper

Variable dimensions

Editions of 5 + 1 AP

In 2006, the first democratic elections are held in Congo. The same year corresponds to strong external demand for copper and cobalt. Several international investors are rushing to Katanga. Among these investors are Chinese. China promises to rehabilitate Congolese infrastructure in exchange for the exploitation of Katanga’s mining resources. Artisanal mining, which began shortly after the fall of the Gécamines industry, and supported by the government, has become a survival practice for Congolese people. They are former Gécamines workers, their family members, unemployed students and families who have fled the war. As a result of economic and territorial instability, artisanal miners live in tarpaulin cities near mining areas.

Mining takes place in mining sites that were once drilled by industrial machinery, with slopes up to more than 100 metres deep.

Equipped with picks, hammers, lamps and raffa bags, the miners climb these slopes in search of heterogeneity (raw material containing copper and cobalt). To extract this heterogeneity, they must excavate tunnels 60 to 100 metres deep, on slopes, before reaching the vein. Then, they go up the slope loaded with more than 50 kilos, several round trips, to constitute a sufficient tonnage for sale to industrialists. It is common for miners to fall victim to landslides; but these losses of life do not stop the march towards gold.

In the cities of tarpaulins, I was struck by the presence of Chinese posters that decorate the interior facades of bars, hotels, houses, hair salons, photo studios… These posters illustrate images of large Western or Asian cities, real or mounted landscapes. You would almost think that these images represent the Congo of tomorrow. Thus, I integrate these posters into my work as a utopian extension of a future resulting from artisanal mining, the loss of human lives, the export of minerals and the continuous displacement of populations.

— Sammy Baloji

Raccord #4, Mine à ciel ouvert noyée de Musonoï

Raccord #7, Usine de Shituru

Mine à ciel ouvert noyée de Banfora #1. Lieu d’extraction minière artisanale, 2010

Détail, site d’extraction artisanale #8, 2011

Zhong Hang Mining, 2009

Cité de Kapata #2. Habitations des ouvriers de la Gécamines occupées par des creuseurs artisanaux, 2011

Portrait #2, Cité de Kapata. Creuseur artisanal à l’intérieur de sa tente en bâche, 2011

Portrait #2, Cité de Kawama, 2011

Congo Far West, 2010-2011

Series of 26 photographs

Archival digital photographs on Hahnemühle PhotoRag

Variable dimensions

Editions of 5 + 1 AP

During his residency at the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren in 2010, Sammy Baloji met Maarten Couttenier, an historian and anthropologist writing his thesis around Charles Lemaire (1863-1925). In 1889, this military man embarked on a journey to Congo, then colonized by the Belgian government, and participated in the definition of the urban space of Leopoldville. Under the guise of a scientific purpose, the mission was actually to organise the occupation of the territories leased by England to Leopolod II in 1894.

Lemaire was accompanied by photographer François Michel and watercolourist Léon Dardenne, who were then responsible for producing a visual trace of the Belgian colonial mission.

Taking possession of the various archives linked to Lemaire, Sammy Baloji did not content himself with reconstructing this expedition, but also rethought its repercussions (historical, sociological, and psychological). Accompanied by Maarten Couttenier, the artist travels to Katanga province and retraces the steps of Charles Lemaire and his companions.

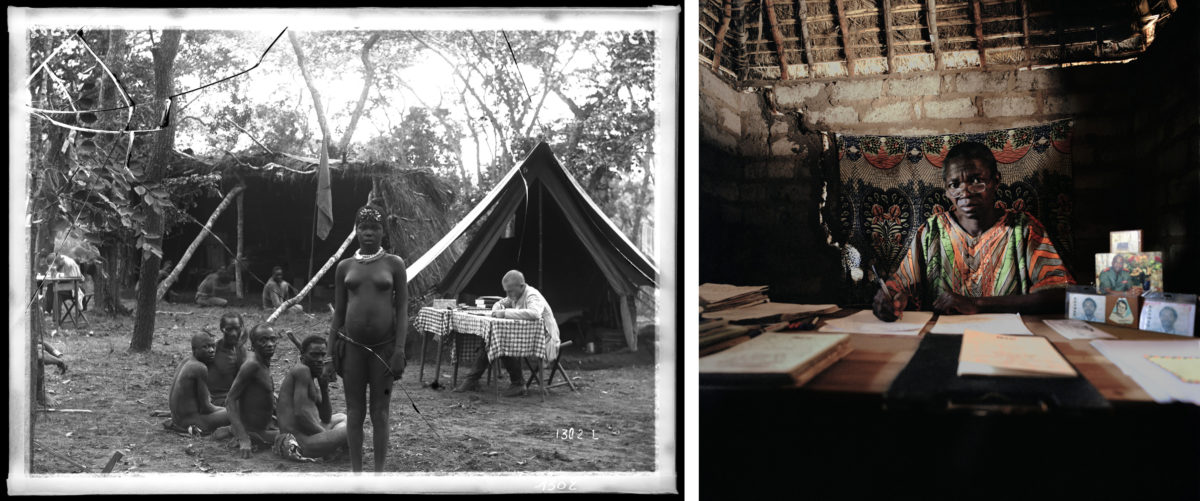

Sammy Baloji’s approach in the Congo Far West series consisted in comparing the archival images taken by François Michel with photographs taken by Baloji himself in today’s DRC. These diptychs thus open up the possibility of a dia-logue between past and present. In addition, the appropriation of archival photographs and watercolours dating from the induced colonial period aims to deconstruct these modes of representation of the dominated produced by the dominant. Through the use of photomontage and the juxtaposition of two distinct images through the diptych, an analysis and questioning of anthropometric photography takes place, which tends to objectify and dehumanise the subjects photographed.

Portrait #1 : Kalamata, Grand Chef Urua sur fond d’aquarelle de Dardenne

Portrait #2 : Femme Urua sur fond d’aquarelle de Dardenne

Portrait #3 : Groupe de femmes Urua sur fond d’aquarelle de Dardenne

Portrait #4 : Groupe d’hommes Urua sur fond d’aquarelle de Dardenne

Allers et retours, 2009

6 inkjet prints on Fine Art Lisse paper, Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth, 305 gr

123 x 153,5 cm (each)

Unique

Coll. Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

“For one of his artistic works Allers et retours (2009), Baloji conducted photographic research dedicated to the skull of the murdered Congolese chief Lusinga, kept in the storerooms of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels (…) The work Allers et retours, consists of a series of six photographs and a video. The photographs show the skull in the way anthropometric photography does, that is, they opt in their representation for the nearly exact reproduction of what seems to be a mere object of science. The black and white prints depict the skull from the front, back, top, side and bottom, on a black fabric background. This multiplication of views in anthropometric photography followed the logic of generating information for a three-dimensional reconstruction. Black fabric was a common background material in 19th century anthropometric photography, often rendered visible in the picture. Similarly, in Baloji’s photographs, the materiality of the fabric has also a striking presence. The integration of the scale in the image points to the purpose of the photography and its inherent functionality in the anthropometric context. Aspiring to produce ‘objective knowledge’ by scientific means, scales and other measurement tools and inscriptions were frequently pictured in anthropometric photography. Furthermore, some of the photographs depict a small plate fixed onto the skull that indicates classificatory data. The photographic lighting underlines the physical features of the skull; it itself reflects the light in sharp contrast with the light-absorbing background. Baloji’s photographic series is organized horizontally. All together, the six images seem to diverge from average anthropometric photography only by their size: Expanding beyond the life-size dimension of the skull, the chosen format – with print dimensions of 123 x 153,5 cm – brings the images close to “fetishization”.”

— Lotte Arndt, Vestiges of Oblivion – Sammy Baloji’s Works on Skulls in European Museum Collections, darkmatter n°101, 2013

Mémoire, 2004-2006

Series of 29 photomontages

Archival digital photographs on satin matte paper

Variable dimensions

Editions of 10 + 1 AP

Lubumbashi was a vital regional center for centuries before the Europeans arrived and became a major industrial centre thanks to the mining of copper under Belgian colonial rule. Nowadays, Lubumbashi, casts a pale shadow of its former glory. In Mémoire, past and present collide. Baloji juxtaposes color photographs of today’s bleak, industrial landscapes with historical images drawn from the archives of the local mining company, which memorialize African and European colonial actors, who toiled for and benefited from the mine. While the resulting images are indictments of the lasting legacies—social, political, environmental—of colonialism, they also recall the economic benefits made by the mines and their ruin after independence. Appropriating and assimilating all of this history, Baloji transforms the diverse temporal and personal fragments into a contemporary reading, in order to open up a way forward.

Untitled #6

Untitled #11

Untitled #17

Untitled #21

Untitled #25