Deniz Eroglu, Baba Diptych, 2016, 2′ 29″, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Deniz Eroglu, Baba Diptych, 2016, 2′ 29″, courtesy de l’artiste

[-]Deniz Eroglu, Baba Diptych, 2016, 2′ 29″, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Deniz Eroglu, Baba Diptych, 2016, 2′ 29″, courtesy de l’artiste

[-]Mona Benyamin, Trouble in Paradise, 2018, 8′30″, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Mona Benyamin, Trouble in Paradise, 2018, 8′30″, courtesy de l’artiste

[-]Mona Benyamin, Trouble in Paradise, 2018, 8′30″, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Mona Benyamin, Trouble in Paradise, 2018, 8′30″, courtesy de l’artiste

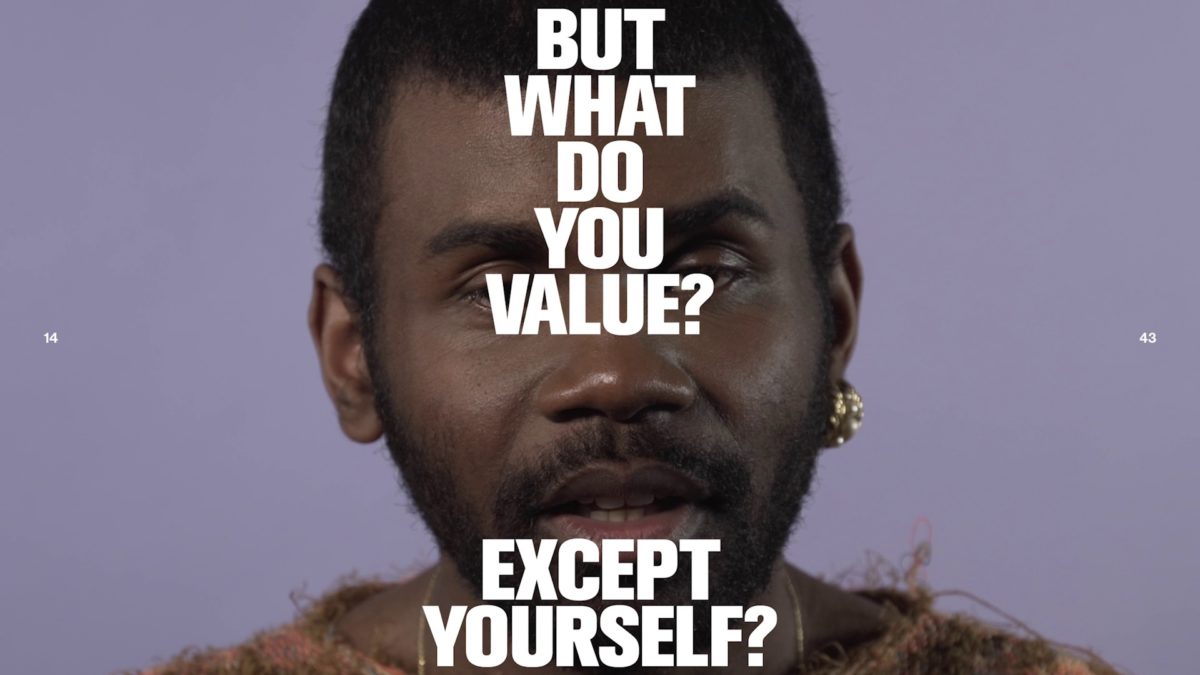

[-]Ndayé Kouagou, GOOD PEOPLE TV – ÉPISODE 1, 2021, 7′23″, courtesy de l’artiste et Nir Altman gallery

[+]Ndayé Kouagou, GOOD PEOPLE TV – ÉPISODE 1, 2021, 7′23″, courtesy de l’artiste et Nir Altman gallery

[-]Ndayé Kouagou, GOOD PEOPLE TV – ÉPISODE 1, 2021, 7′23″, courtesy de l’artiste et Nir Altman gallery

[+]Ndayé Kouagou, GOOD PEOPLE TV – ÉPISODE 1, 2021, 7′23″, courtesy de l’artiste et Nir Altman gallery

[-]Rayane Mcirdi, La légende d’Y.Z., 2016-2017, 14′, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Rayane Mcirdi, La légende d’Y.Z., 2016-2017, 14′, courtesy de l’artiste

[-]Rayane Mcirdi, La légende d’Y.Z., 2016-2017, 14′, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Rayane Mcirdi, La légende d’Y.Z., 2016-2017, 14′, courtesy de l’artiste

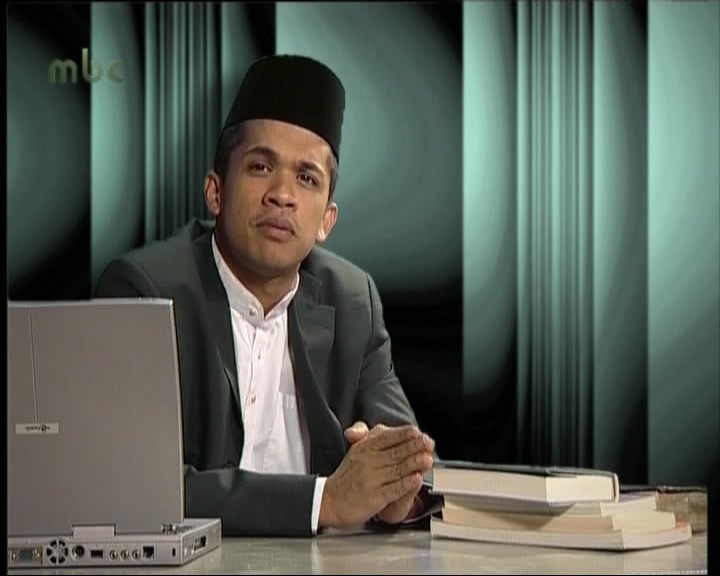

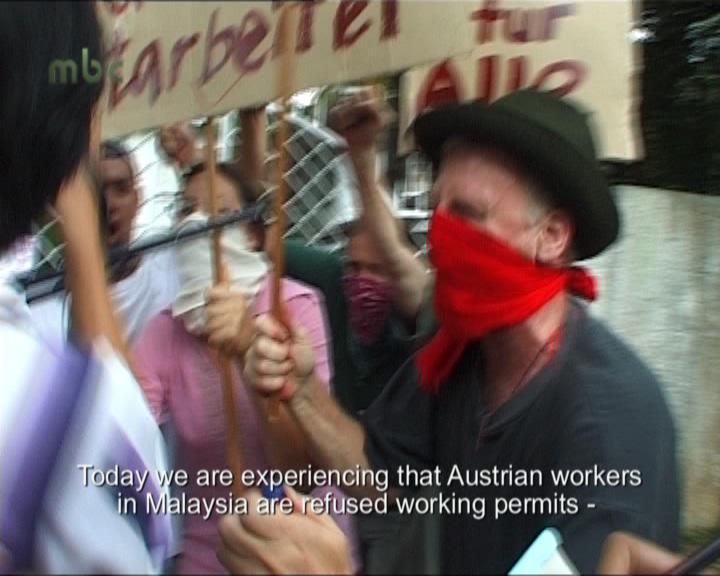

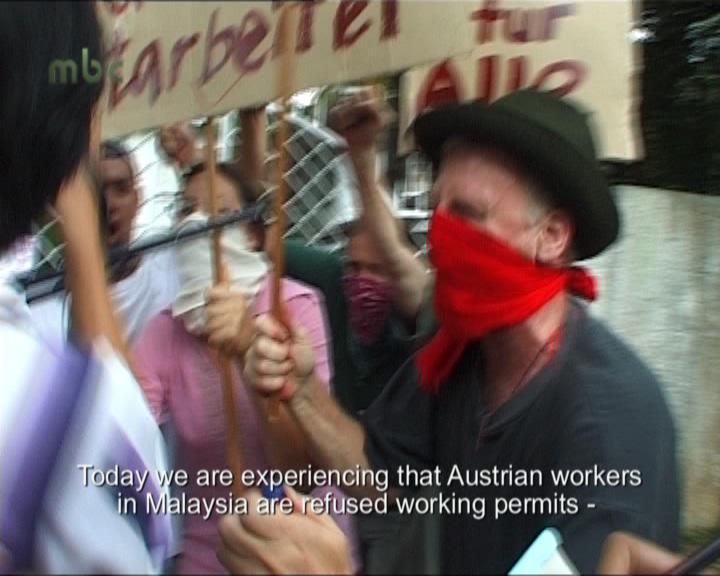

[-]Wong Hoy Cheong, Re: Looking, 2002-2003, 30′, commandité par le Schauspielhaus de Hambourg, le Theater Ohne Grenzen de Vienne et la Biennale de Venise de 2003, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Wong Hoy Cheong, Re: Looking, 2002-2003, 30′, commandité par le Schauspielhaus de Hambourg, le Theater Ohne Grenzen de Vienne et la Biennale de Venise de 2003, courtesy de l’artiste

[-]Wong Hoy Cheong, Re: Looking, 2002-2003, 30′, commandité par le Schauspielhaus de Hambourg, le Theater Ohne Grenzen de Vienne et la Biennale de Venise de 2003, courtesy de l’artiste

[+]Wong Hoy Cheong, Re: Looking, 2002-2003, 30′, commandité par le Schauspielhaus de Hambourg, le Theater Ohne Grenzen de Vienne et la Biennale de Venise de 2003, courtesy de l’artiste

[-]Hilary Galbreaith, Bug Eyes Episode 1, 2019, 27′, Production In Extenso, courtesy de l’artiste et In extenso

[+]Hilary Galbreaith, Bug Eyes Episode 1, 2019, 27′, Production In Extenso, courtesy de l’artiste et In extenso

[-]Hilary Galbreaith, Bug Eyes Episode 1, 2019, 27′, Production In Extenso, courtesy de l’artiste et In extenso

[+]Hilary Galbreaith, Bug Eyes Episode 1, 2019, 27′, Production In Extenso, courtesy de l’artiste et In extenso

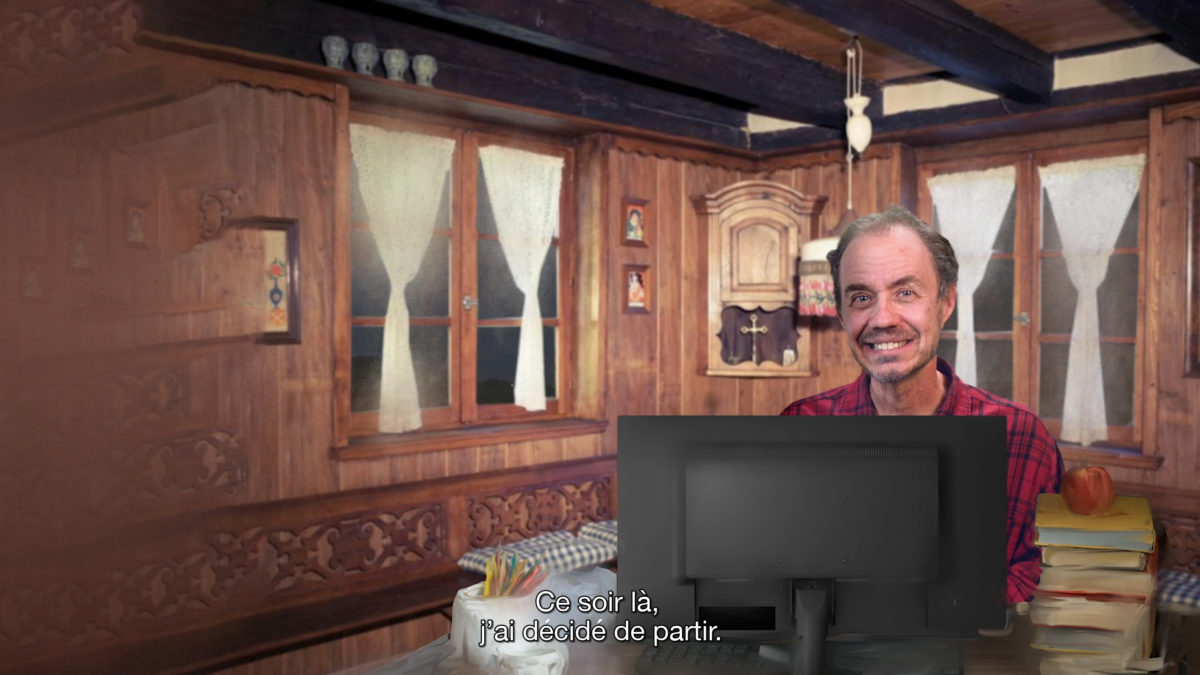

[-]Gaspar Willman, Slonfa Shenfa, 2021, 11’49”, courtesy of the artist

Gaspar Willman, Slonfa Shenfa, 2021, 11’49”, courtesy of the artist

Gaspar Willman, Slonfa Shenfa, 2021, 11’49”, courtesy of the artist

[+]Gaspar Willman, Slonfa Shenfa, 2021, 11’49”, courtesy of the artist

[-]

Deniz Eroglu, Baba Diptych, 2016, 2′ 29″, courtesy de l’artiste

Deniz Eroglu, Baba Diptych, 2016, 2′ 29″, courtesy de l’artiste

Mona Benyamin, Trouble in Paradise, 2018, 8′30″, courtesy de l’artiste

Mona Benyamin, Trouble in Paradise, 2018, 8′30″, courtesy de l’artiste

Ndayé Kouagou, GOOD PEOPLE TV – ÉPISODE 1, 2021, 7′23″, courtesy de l’artiste et Nir Altman gallery

Ndayé Kouagou, GOOD PEOPLE TV – ÉPISODE 1, 2021, 7′23″, courtesy de l’artiste et Nir Altman gallery

Rayane Mcirdi, La légende d’Y.Z., 2016-2017, 14′, courtesy de l’artiste

Rayane Mcirdi, La légende d’Y.Z., 2016-2017, 14′, courtesy de l’artiste

Wong Hoy Cheong, Re: Looking, 2002-2003, 30′, commandité par le Schauspielhaus de Hambourg, le Theater Ohne Grenzen de Vienne et la Biennale de Venise de 2003, courtesy de l’artiste

Wong Hoy Cheong, Re: Looking, 2002-2003, 30′, commandité par le Schauspielhaus de Hambourg, le Theater Ohne Grenzen de Vienne et la Biennale de Venise de 2003, courtesy de l’artiste

Hilary Galbreaith, Bug Eyes Episode 1, 2019, 27′, Production In Extenso, courtesy de l’artiste et In extenso

Hilary Galbreaith, Bug Eyes Episode 1, 2019, 27′, Production In Extenso, courtesy de l’artiste et In extenso

Gaspar Willman, Slonfa Shenfa, 2021, 11’49”, courtesy of the artist

Gaspar Willman, Slonfa Shenfa, 2021, 11’49”, courtesy of the artist

“Television is conversant on a million topics and broadcasts itself as an exquisite generalist, an encyclopedic skimmer that avoids specificity like Dracula dodging the Cross. It flaunts a fluency in more than a few languages and speaks in hundreds of voices, juggling gender and race like a spirit trying on bodies for size, like a manic quick-change artist on a binge.”

—Barbara Kruger, “September 1989” in Remote Control, The MIT Press, 1993 [1989], p. 48

Taken from artist Barbara Kruger’s column on television that was published regularly in Artforum, this excerpt shrewdly dissects television’s versatility (in contents, genres, and rhythms), a quality that is as much a strength as it is a flaw. TV, we are told, “avoids specificity like Dracula dodging the Cross”. Through this visually evocative metaphor, Kruger describes the ever-changing flow of programs on TV, simultaneously revealingthe scope of its influence. When her text was published in the late 1980s, television’s reach seemed particularly tentacular—whether geographically, linguistically, or thematically—making it an inexhaustible source for artists exploring the socio-political breadth of image-making, such as Kruger herself.

Today, television’s modes of production and reception have changed, even its physical form has been altered, slimmed, and flattened. The technology’s rapid change has instigated today’s digital screen-culture, yet analog television and its aesthetics persist as references, notably in the practices of artists born between the 1980s and late 1990s1. Like Dracula dodging the Cross gathers works by Mona Benyamin, Deniz Eroglu, Hilary Galbreaith, Ndayé Kouagou, Rayane Mcirdi, Gaspar Willmann, and Hoy Cheong Wong— seven artists who continue to interrogate TV with fascination, skepticism and nostalgia. They use, appropriate, and disturb TV’s functions, as well as its visual and discursive codes. These artists subvert the assumption that TV constitutes a “universal” cultural reference, injecting linguistic, visual and musical elements that relate to specific cultural contexts, geographical or political positionings. Taking advantage of the immediacy of TV’s aesthetics and grammar, they weave within them tales of diasporic transmissions, alternatives and parodies to colonial histories, or reflections on misinformation and cultural appropriation. Disguised under TV’s format, these narratives rely on the imagery’s accessibility to produce a critical discourse, but one that is resolutely imbued with a sense of nostalgia towards a highly familiar object.

Created and unravelling in different settings, these works share a methodology: they emanate from a similar economy of means (material, financial, and above all human) that diverges from TV’s own production modes. Each of these artists stages themselves, their friends and families or other amateurs as the main characters of their work, leading to uncanny performances that are not based on the actors’ virtuosity. They ultimately blur the lines between performance (as an artistic medium) and acting (as a form of performing arts). The artists are then faced with the challenge of filming their loved ones in a moment of vulnerability, all while dodging a voyeuristic gaze.

More than symptoms of the deskilling of art, these processual, visual, and conceptual choices are practical. They reveal the very conditions of the works’ production, some of which were made while the artists were still students (Mona Benyamin, Rayane Mcirdi, Gaspar Willmann) or not yet set on the path of art (Deniz Eroglu). Others claim a Do-It-Yourself aesthetic in relation to ecological engagements (Hilary Galbreaith) or concerns of accessibility (Ndayé Kouagou). Within these recent practices, Hoy Cheong Wong’s film stands out as a pioneering work that deftly perceived the intricate links between the small screen and misinformation, eventually exemplifying this quote by Trinh T. Minh-ha: “(…) truth lies in between all regimes of truth”2.

Staged in the imaginary New New Orleans, Hilary Galbreaith’s (American, b. 1989) Bug Eyes series unfolds like a reality TV show marked by kafkaesque ridicule: the show’s participants are humans-turned-insects, played by puppets that the artist made. In line with this DIY methodology, Galbreaith inserts her own face as a cheerful omnipresent figure that looks down on the competitors in the series’ first episode. Subverting a genre that has come to epitomize American entertainment, Galbreaith imbues it with surrealism and tragicomedy.

Rayane Mcirdi’s (French, b. 1993) La légende d’Y.Z recreates scenes from martial arts movies, which were generally produced in Asia (specifically in Hong Kong), but largely exported and broadcast on Western TV. This video reveals the wide influence of the genre, but also how its dissemination through Western circuits paved the way for certain cultural stereotypes. The impressive acting of the protagonist,Yacine Zerguit (Mcirdi’s cousin), hints to the impact of these stereotypes on contemporary performances of masculinity, eventually offering a glimpse of the life of a young man of Algerian descent in today’s France.

Another kind of remake centeringmasculinityis at play in Deniz Eroglu’s (Danish, b. 1981) Baba Diptych. Here, TV appears as a “domesticated medium”3: the work is made of footage shot by the artist as a teenager, capturing his father —a Turkish immigrant who stopped his acting career short when he got to Denmark to open a Kebab restaurant— singing in his native language. Next to this touching home movie, another screen features Eroglu impersonating his father and singing the same song, twenty years later. This diasporic tale of transmission of language and music highlights a methodology of working with family, common to other artists in the program.

The involvement of her own parents is indeed a recurrent strategy for Mona Benyamin (Palestinian, b. 1997). In Trouble in Paradise, the remake gives way to parody: the work activates codes from American sitcoms (from laugh tracks to stereotypical gender-roles), only to hijack them by tackling the illegal Israeli occupation of Palestine through dark humor. Casting her parents as the protagonists, Benyamin renders the enterprise endearing, playing on their limited knowledge of English, their amateur performance, and their first-hand experience of the Nakba (1948) and the Naksa (1967), which they never talk about.

Titled Slonfa Shenfa (Alsatian vernacular for “Sleeping, working”), Gaspar Willmann’s (French, b. 1995) video exemplifies a play on deskilled performances, all while tackling the perils of service-to-user platforms. Played by an actor hired online, the main protagonist named Cliff leaves his native Alsace for “America”. Using an alternative circuit of film-production, the work offers a pastiche of a classical Hollywood story, the iconic journey of the American dream, thus forming a melancholic commentary on contemporary conditions of labors.

Hoy Cheong Wong (Malaysian, b. 1960) replicates the forms and strategies of political documentaries in Re: Looking only to posit a fictitious and absurd narrative in which Malaysia would colonize Austria. Wong’ visionary exploration of misinformation (what we refer to as fake news today) echoes Ndayé Kouagou (French, b. 1992)’s Good People TV, which parodies the contemporary audience-anchor rapport, subverting the assumed authority of TV presenters.

[1] Most of these artists were born right when the CRTs and their accompanying VHS were to become obsolete.

[2] Trinh T. Minh-ha, “Documentary is/ Not a name”, October, Vol. 52 (Spring, 1990), p. 76

[3] An expression borrowed from media scholar Roger Silverstone. See: Milly Buonanno, The Age of Television. Experiences and Theories, Translated by Jennifer Radice, The Chicago University Press, 2007.

Exhibition journal