Things that move (us)

Earthquakes, tremors, vibrations, vacillations, wiggles, wobbles and other movements that, when registered on the screen of the seismograph or in the body’s memory, make of us their witnesses.

We can perceive the difference between natural disasters – an earthquake or a tsunami, something unpredictable, to which we have no choice but to submit – and those made by man – an act of terrorism, the failure of a security system in a nuclear power plant or

a financial crash. All of these events have their place on the spectrum of risk, but disaster itself, in all its forms, is always the same.

If disaster, in its very etymology, refers to the idea of being born under a “bad star”(dis-astro), proclaiming a doomed, sealed fate, catastrophe is also that which turns back on itself (kata-strophê). It is not only a reversal, but something that comes back, that repeats itself endlessly, stubbornly, irrevocably.

Far from apocalyptic representations, what I wish to make visible, poetic, is the chaos of a world in decline, its movements, its tremors and vacillations, its falls. The words of Walter Benjamin in his text on The Destructive Character resonate throughout this attempt: “What exists he reduces to rubble – not for the sake of rubble, but for that of the way leading through it.”

— Ali Cherri

In the presence of a catastrophe

“This is what terrifies in catastrophe: that it speaks with such undivided purity. And what catastrophe says when it speaks constitutes a new form of ‘catastrophic information’, in the words of Paul Virilio, a ‘new knowledge’.”2

It is extraordinary to observe how the realm of asphalt and urban infrastructure in contemporary cities sprawls and modifies human consciousness into a state of de-rootedness regarding its geological and non-human environment. If we consider contemporary capitalism as an object of high abstraction and current wars for resources the playground of the utmost cynicism, wouldn’t one of the most appropriate stances be to remind oneself what lies beneath the surface and presents a permanent threat to our fragile existence? This age-old questioning has been accompanying human civilisation since its beginnings and nourished the apocalyptic visions and testimonies about disasters and phantasms about the laws of nature which remain largely invisible. This stance also opens up a space for speculation that enables us to dwell on what drives the “deep-underneath” on which we stand and which gives us the mobility and possibility to use, and too often misuse, its potentials.

In his exhibition On Things that Move, Ali Cherri searches for a new visual language of a natural catastrophe, a disaster in its most pure form where human subjectivity has little space for intervention. The exhibited works give shape to an intentional dramatization through which the artist addresses the science of seismology in order to find the answers to human blindness, to keep the memory awake, to gently scream to the generations that are coming about how senseless it is to repeat the same man-made disasters, and in doing so to fail repeatedly. In Errance, a strolling banner fades from white to black and back to white and represents this never-ending law of cyclic nature and also mimics seismograph’s continuous movement and the labour of inscribing disaster in its becoming.

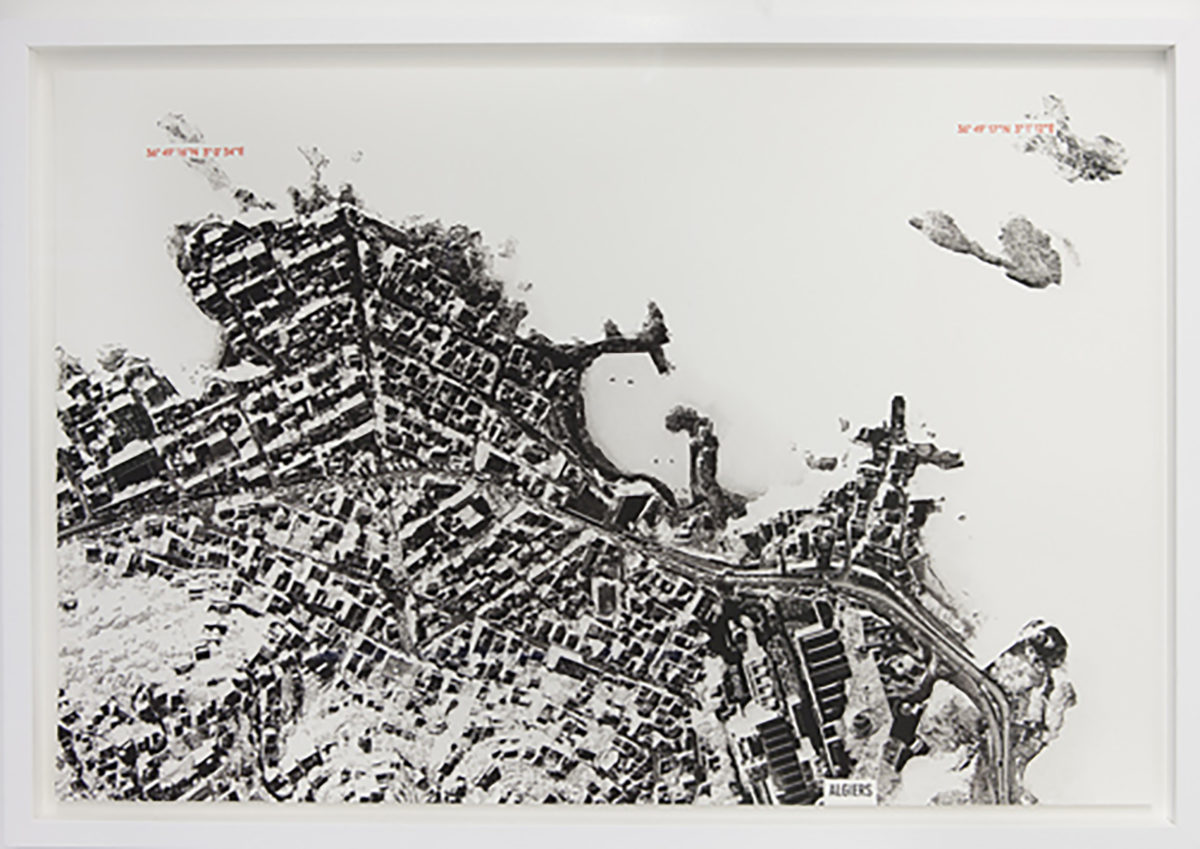

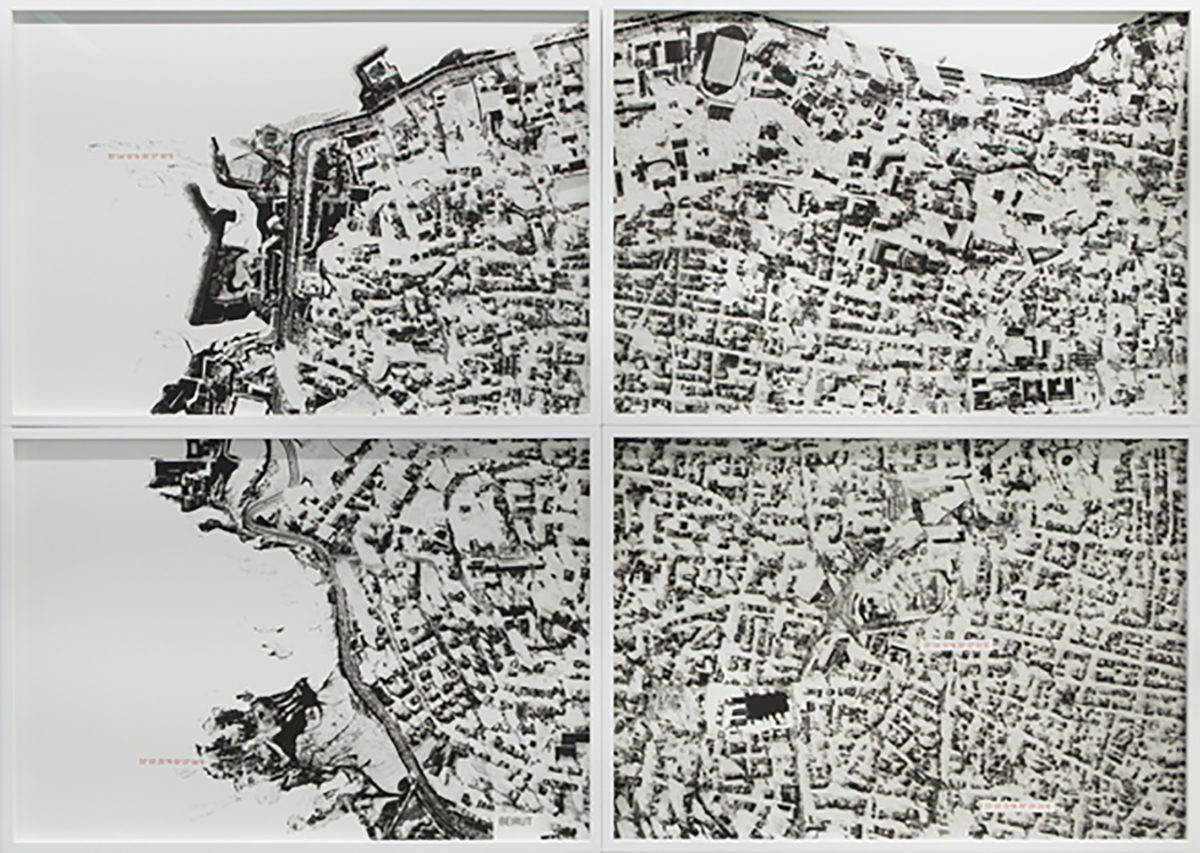

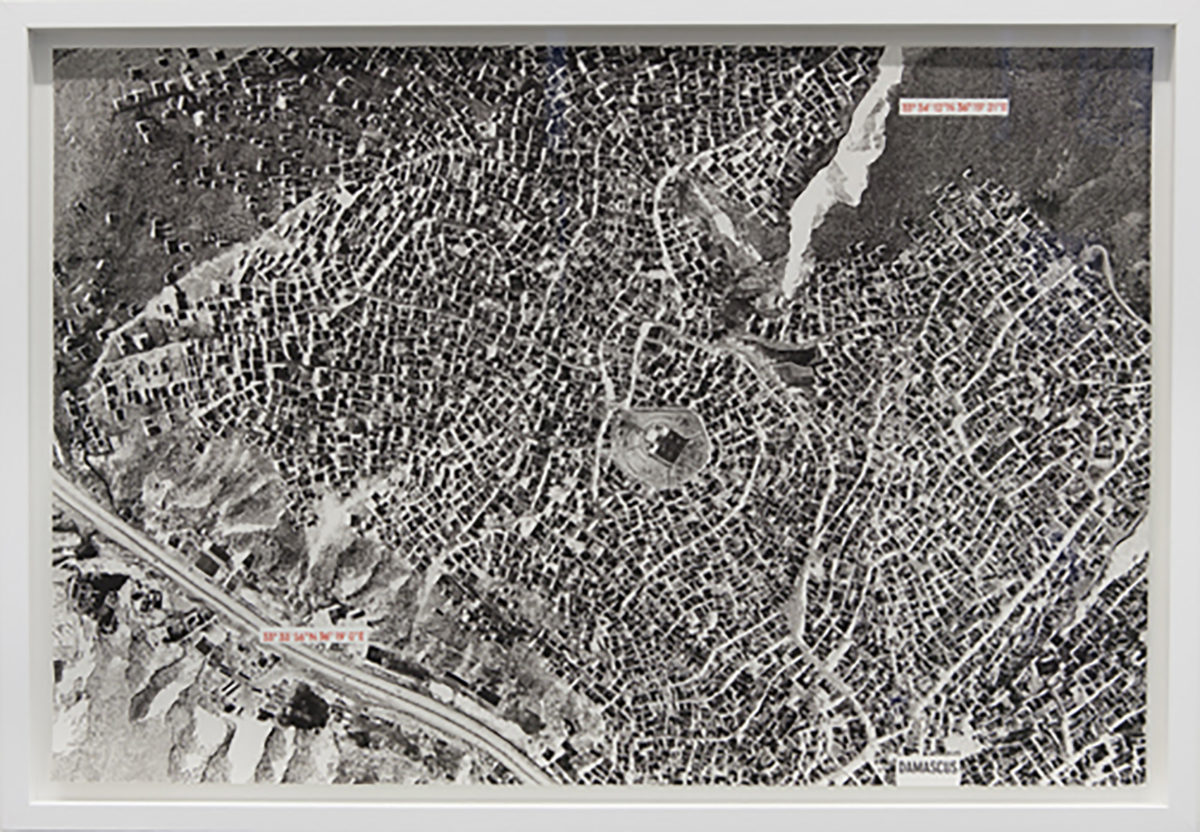

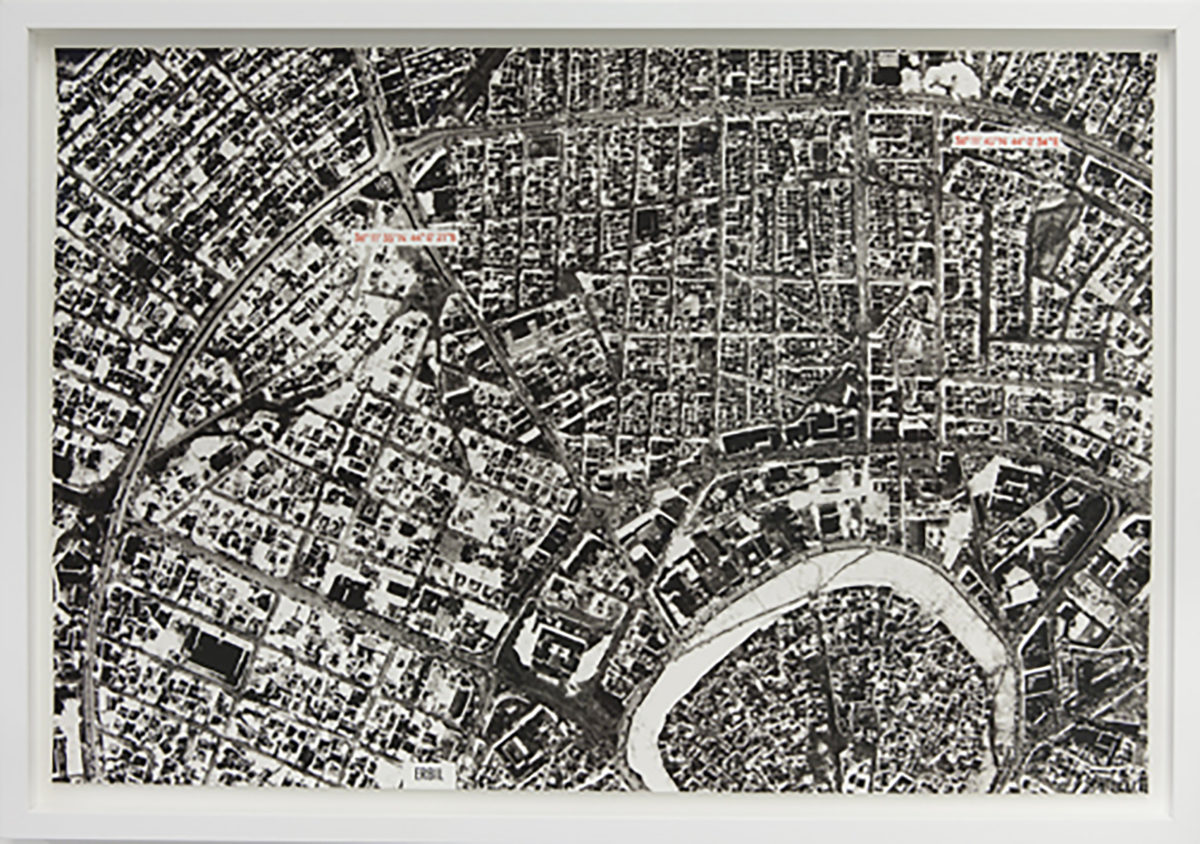

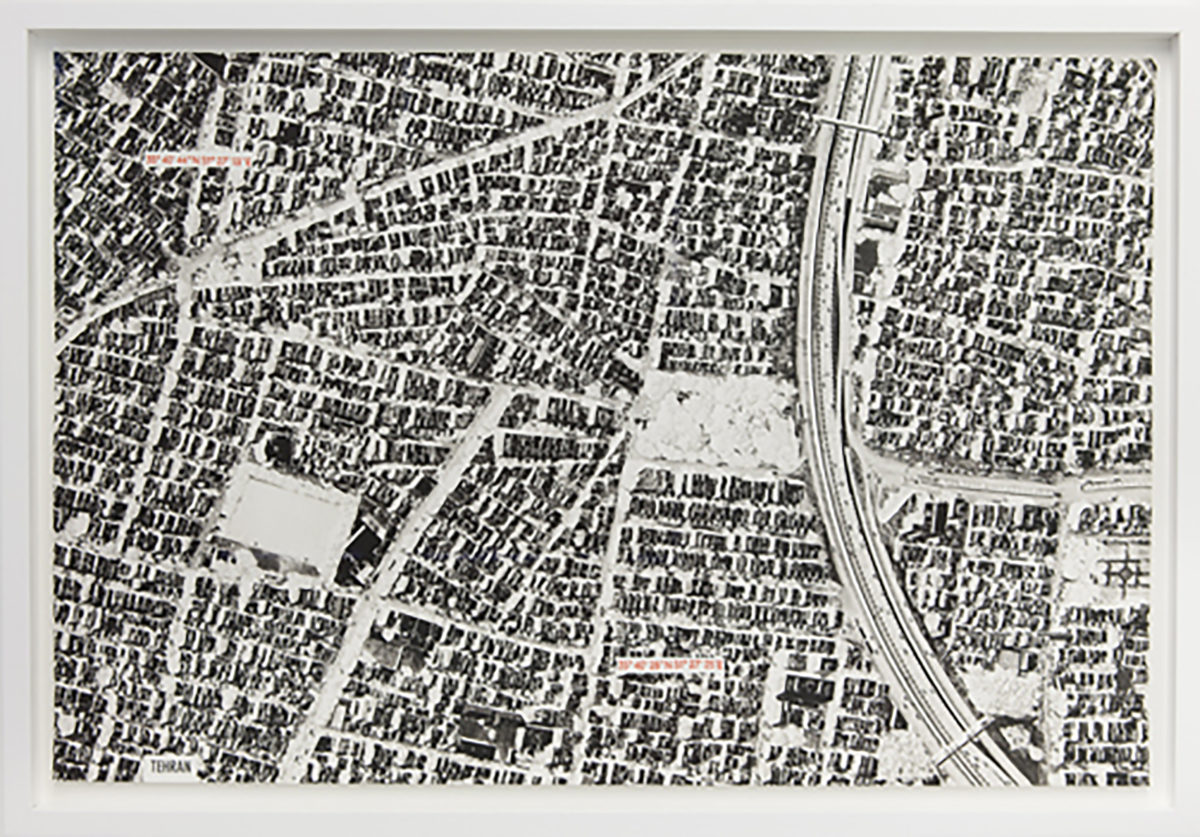

Paysages tremblants are black and white lithographs of aerial views of Beirut, Damascus, Algiers, Teheran and Erbil with red stamps that mark the polar coordinates of the fault lines running underneath these cities. The maps are reminiscent of well-known photographs of cities destroyed in the Second World War, or more recent image filmed by hovering drones, but without a clear reference about whether the given city is in the state before or after the catastrophe. What they offer though is retrieval of memory that we share and too often suppress, as well as a possibility to transform this information into a metaphor for the unrest that envelops those cities ceaselessly. When the use-value of an object expires, its historical importance and auratic presence gains our attention.

In that way, for his work Atlas 1876 – 2014, Cherri placed an old atlas from 1876 inside a resin frame and thus stopped the ageing process of this book of obsolete knowledge. Similarly, although created in unawareness of Mangelos’ conceptual artworks, Ali Cherri’s Archeologie are reminders of the amazing series Paysages de la mort or Paysage de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (1950s-1970s) of that late Croatian/Serbian conceptual artist. The maps of the old atlas are blackened, wiped away from their primary function as orientations and recognizable territories, and morphed into a thick black mass on paper.

The Disquiet film opens with a quote from Bertolt Brecht’s poem, announcing how we might perceive the apocalyptic times of our current era, or of any era actually. The quote is both disheartening as it is true time and time again:

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing

About the dark times.3

Sequences of long walks in nature alternate with seismographic mechanisms inscribing a disaster-in-becoming and then with history of recent earthquakes in Lebanon through archival images and old drawings. An inevitability of natural and political synchronicities in a given region, that reigns in the voiceover narration, is transformed in the last part of the film. A space for hope is introduced, where it is suggested that one has to leave the document(ary) mode of narrating and enter into a speculation, in solitude and lucidity of one’s own mind and beliefs. Démembrement participates as a “grand finale” in creating a poetic although unsettling atmosphere, especially alluding to how after a catastrophe we are left in a world that is disjointed. The work’s mythological and dramatic presence hovers above us as if testifying of the inevitable natural disasters while they are already taking place, in slow motion.

— Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez

1. Walter Benjamin, Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, translated by Edmund F.N. Jephcott, 1986.

2. Matthew Gumpert, The End of Meaning, 2012

3. Bertolt Brecht, Poems, 1913–1956, John Willett, éd. Ralph Manheim, 1976