Sculptors of the World

In the contemporary landscape, buffeted by images and all the forms that they take, this second edition of No Limit really drives the point home. The tone was already set last year, with our first tribute to the idea of liberty, which extends directly from the field of creation. This time, the work of the three artists brought together here can be distinguished by a desire to depart the known world in order to restore its anomalies, all while avoiding the pitfalls of the manipulation of aesthetic reality, let alone the misrepresentation of difficult or problematic actuality. By taking Mohamed El baz’s working method as an example, we may say that each of these artists approaches their investigations with a personalized “tool-box”, equipped by personal history and the specific context in which they conducted their current research, which calls into question part or all of their previous research. It ultimately allows the artist to coax ideas into being without stripping them of their essential mystery, to do away with convention and cliché while still able to leverage the archetypes that gave rise to them, and sometimes even managing to reveal their beauty. It is certainly very powerful, to be able to impose a filter on the surrounding world, one that re-enchants only to manage to more precisely highlight the distortions, manipulations and abuses of power that go on, and to finally put art in its proper place among the global turmoil. Each one of them animates his defiance differently, but the general method is the same: telescoping the real and the imaginary. All three of the artists arrive at their questioning of the real through poetic shifts of perspective.

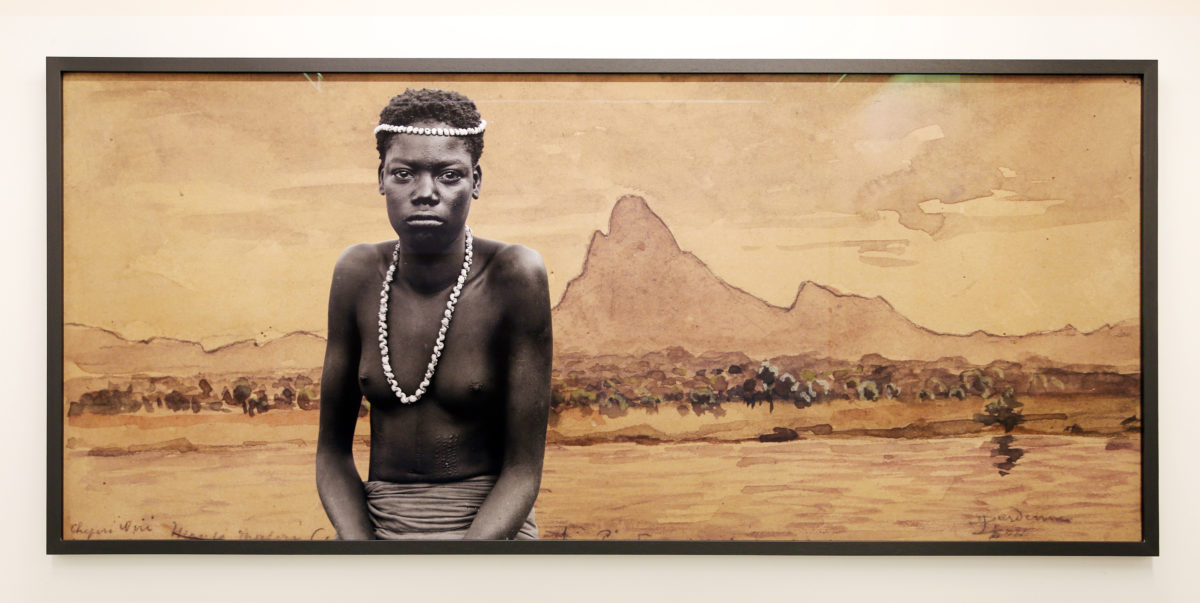

On the trail of the ever-present colonial gaze, Sammy Baloji, full of the historical and contemporary reality of his people in the Katanga region in south Congo, superimposes pseudo-scientific, almost dehumanising photographic portraits on old watercolour landscape paintings from the end of the 19th century. The contrast of the crude and raw presence under the photographer’s scrutiny and the insipid sentimentality of the landscapes melts these images into one another in order to reveal something else entirely, leading the viewer to questioning the contemporary reality and the ways in which it has been informed by recent history.

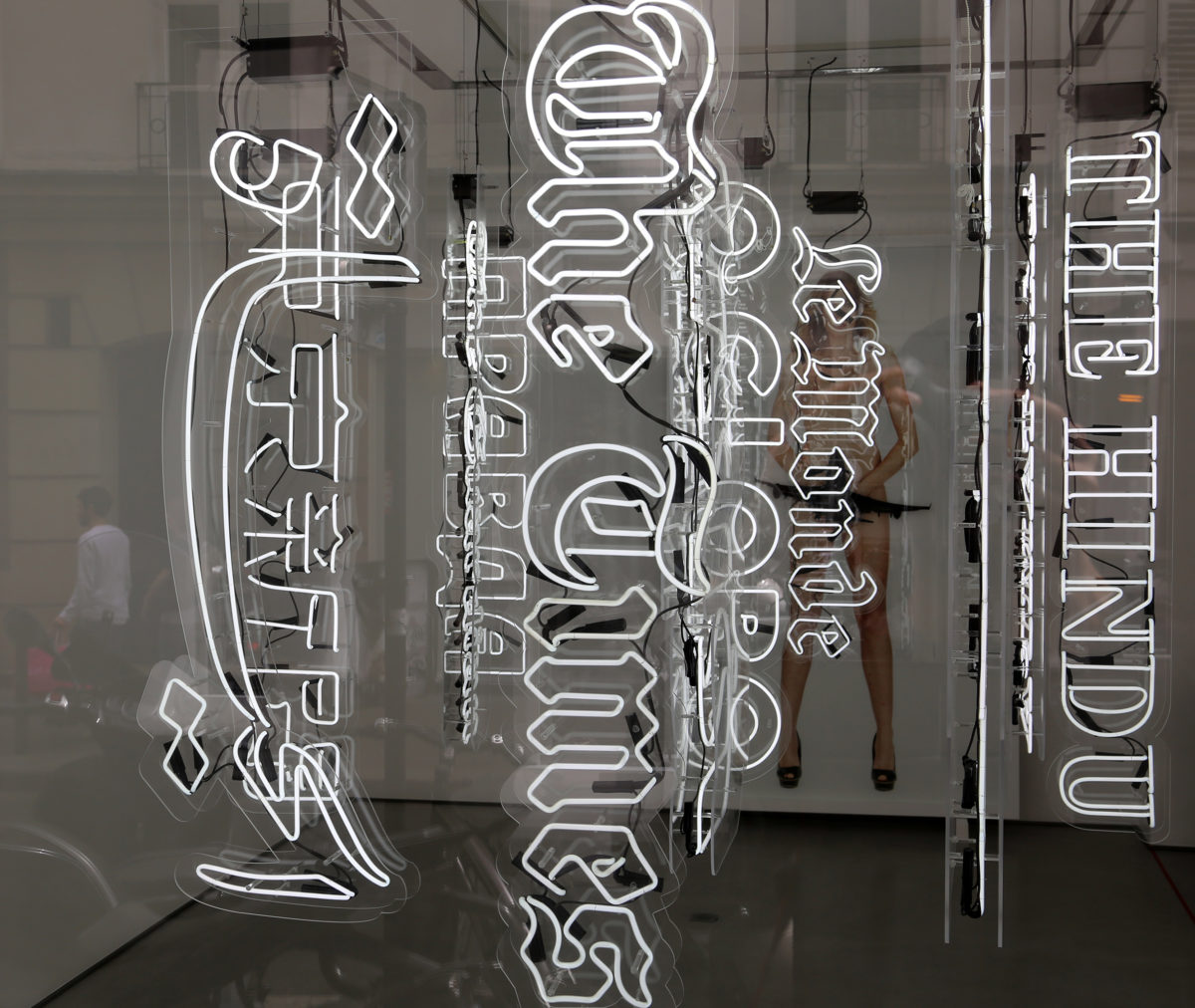

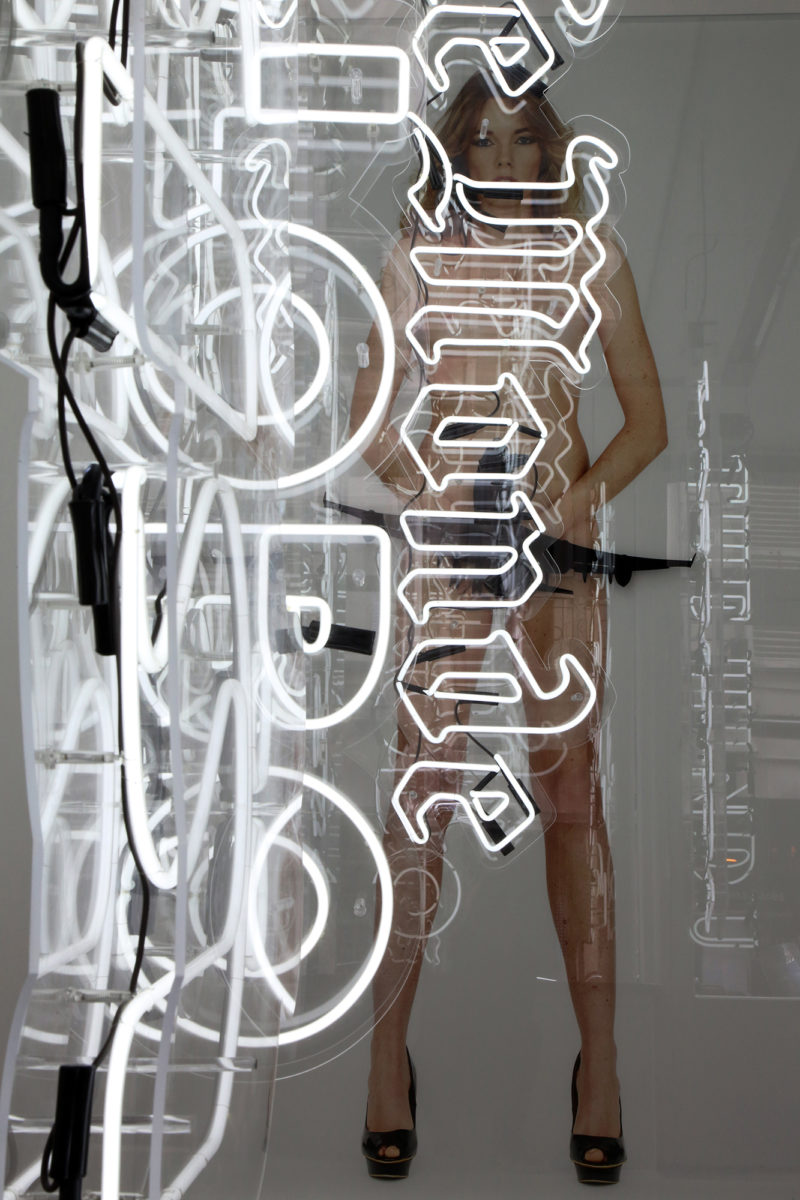

Memory and social embeddedness also play an essential role in the works of Mohamed El baz and James Webb. They share their notorious interest in using subtle and interactive sound devices that call into question the disse-mination and the reception of reality and all its possible interpretations by the listener. Both also make use of text as a poetic vehicle that allows a shift from narration to meaning and reciprocity. Finally, light and its sensory effects advocate for an overview of a planet that too often escapes our attention. And if we find social and political engagement in these works, it is only ever thanks to a subtle intelligence and sensitivity in the observer, and never because it is obviously served up at first glance.

All three are attuned to the world and its dysfunctions, but always through a humanistic commitment rather than a Manichean or dogmatic one, and always in the pursuit, above all, of artistic integrity.

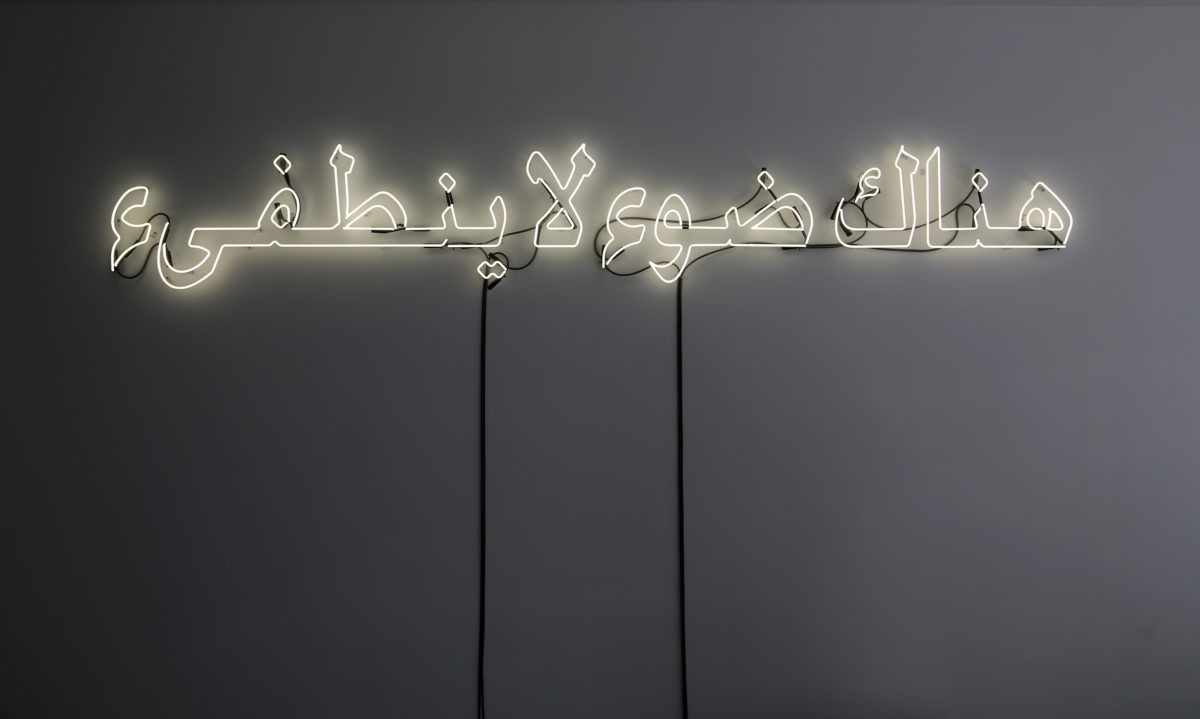

Both Webb and El baz have left, in Amman, within the framework of exhibitions produced by and for Darat al Funun and under the auspices of Abdellah Karroum, huge, calligraphic traces of their presence on the walls of the city. A neon lyric, in Webb’s case – THERE IS A LIGHT THAT NEVER GOES OUT, borrowed from The Smiths – that resonates well with El baz’s black plexiglass declara-tion: IMAGINE / THE RIVERS BURNING IN THE DIS-TANCE / WE HEAR THE SILENCE AND / SUDDENLY THE MUSIC COMES / TOWARDS US TO KILL US / AND THE DANCE CONTINUES EVEN / MORE BEAUTIFUL BENEATH THE WHITE SUN… Both very direct addresses, in line with the geo-political situation of the city, legible by all and well-disposed to all manner of subjective interpre-tation; neither of these interventions constitutes a form of cultural activism but rather manifestations of a sharp, conscientious take on the imperfections of the world. All the while underlining an essential question: how does one bring life to a work that is literally written into a specific context, one that lends it its entire energy and reason for being? How to continue and carry this work elsewhere, to a gallery, for example? And the various answers display the essence of the works themselves: for El Baz, it is in how they resist naming “survivors”, for Webb, it is in how they lend themselves to a variety of interpretations, for Baloji, it is in how they resurrect the traces of recent history. From a critical perspective and from the multiple viewpoints it gives rise to, this exploration, tirelessly re-imagined in art, truly has No Limit. And, after disassembling, documenting and reconstructing, the three artists finally come face to face with the ultimate implication of their efforts: what does it mean to produce a work grounded in reality?

— Nadine Descendre