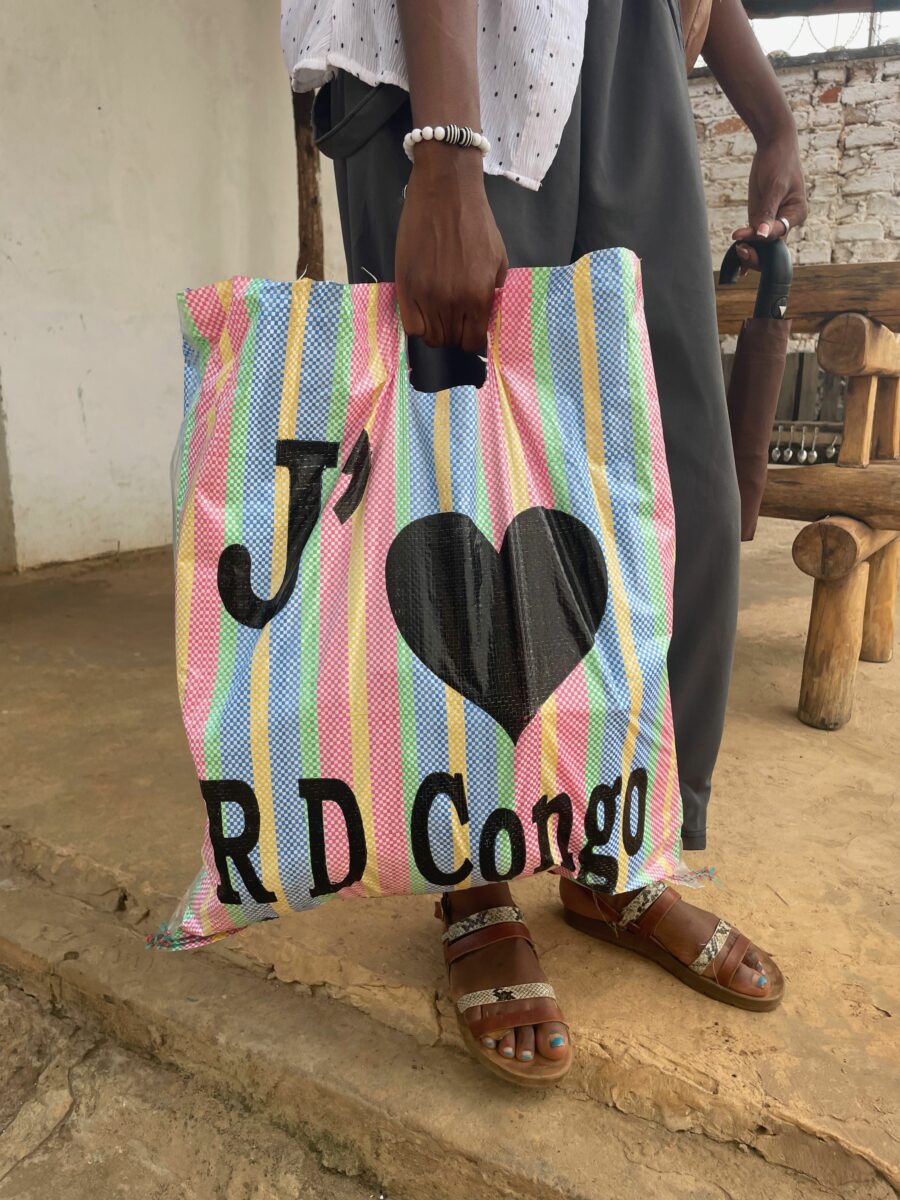

J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Shopping bag woven from polypropylene “taux du jour.” Courtesy of the artists. © Lafleur & Bogaert.

Lafleur & Bogaert

[+]

Lafleur & Bogaert

[-]

Godelive Kasangati Kabena

Mbwa: Now Mine, 2025. Blown glass, velvet pillow, duvet. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[+]

Godelive Kasangati Kabena

Mbwa: Now Mine, 2025. Blown glass, velvet pillow, duvet. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[-]

Nilla Banguna

Wankito (umwanakaji). La femme forte, 2023. Printed fabrics designed and produced by Nilla Banguna, in collaboration with Patricia Banguna Kazadi, Josephine Kyungu Muloba, and Fernande Musha Sebelwa. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[+]

Nilla Banguna

Wankito (umwanakaji). La femme forte, 2023. Printed fabrics designed and produced by Nilla Banguna, in collaboration with Patricia Banguna Kazadi, Josephine Kyungu Muloba, and Fernande Musha Sebelwa. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[-]

Mickael-Sltan Mbanza

Nsala, 2025. Black and white video, 10 min. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[+]

Mickael-Sltan Mbanza

Nsala, 2025. Black and white video, 10 min. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[-]

Pendezâ Mulamba

Mon chant, 2024. HD video, colour, sound, 6 min. 5 sec. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[+]

Pendezâ Mulamba

Mon chant, 2024. HD video, colour, sound, 6 min. 5 sec. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[-]

Sixte Kakinda

Monologue, 2019-2025. Drawing. Courtesy of the artist. Graphisme and design: Maëlle Brientini. © Tadzio.

[+]

Sixte Kakinda

Monologue, 2019-2025. Drawing. Courtesy of the artist. Graphisme and design: Maëlle Brientini. © Tadzio.

[-]

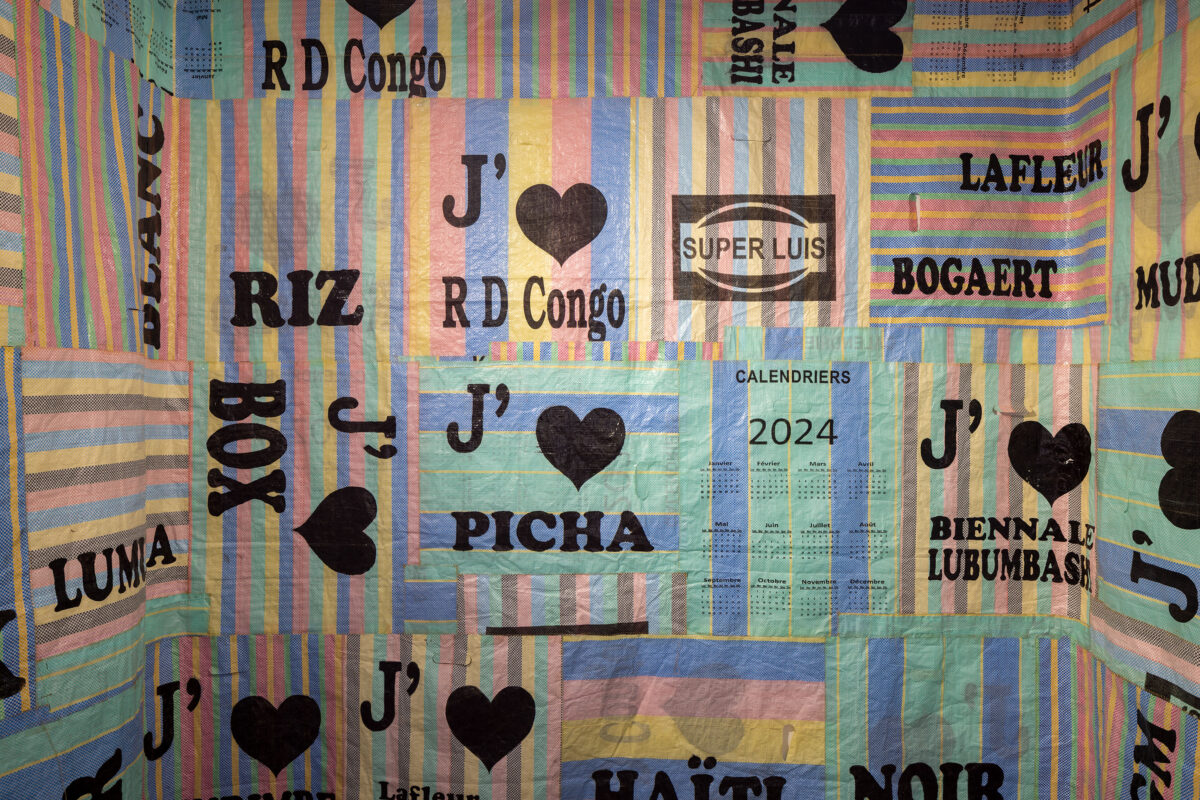

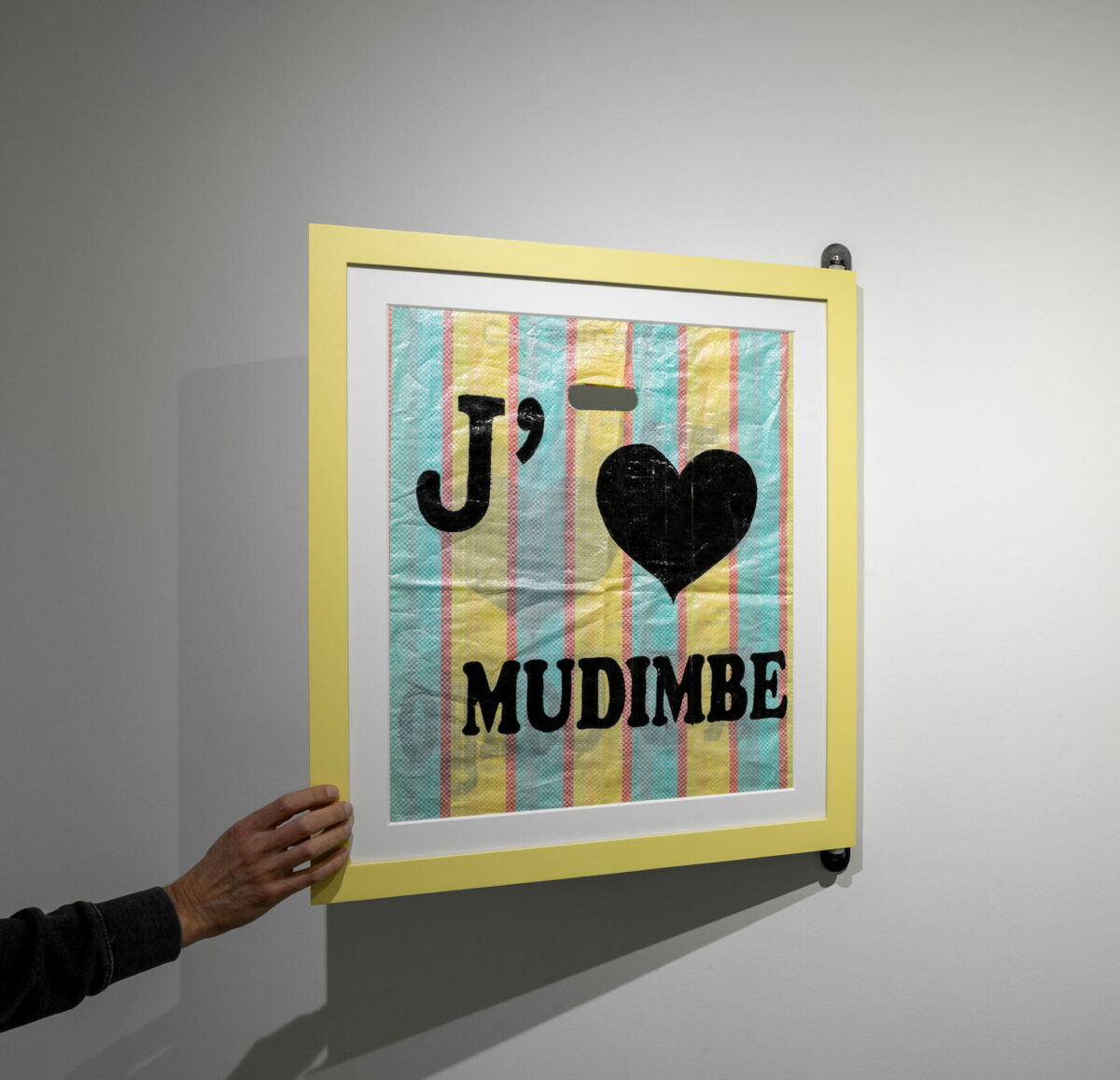

Lafleur & Bogaert

Lafleur & Bogaert, J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Collage, lettres composées à la main sur des sacs de courses cousus avec du fil de cuivre. Courtesy de l’artiste. © Tadzio.

[+]

Lafleur & Bogaert

Lafleur & Bogaert, J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Collage, lettres composées à la main sur des sacs de courses cousus avec du fil de cuivre. Courtesy de l’artiste. © Tadzio.

[-]

Nilla Banguna

Wankito (umwanakaji). La femme forte, 2023. Printed fabrics designed and produced by Nilla Banguna, in collaboration with Patricia Banguna Kazadi, Josephine Kyungu Muloba, and Fernande Musha Sebelwa. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[+]

Nilla Banguna

Wankito (umwanakaji). La femme forte, 2023. Printed fabrics designed and produced by Nilla Banguna, in collaboration with Patricia Banguna Kazadi, Josephine Kyungu Muloba, and Fernande Musha Sebelwa. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[-]

Lafleur & Bogaert

J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Shopping bag woven from polypropylene “taux du jour.” Courtesy of the artists. © Lafleur & Bogaert.

[+]

Lafleur & Bogaert

J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Shopping bag woven from polypropylene “taux du jour.” Courtesy of the artists. © Lafleur & Bogaert.

[-]

Godelive Kasangati Kabena

Mbwa: Now Mine, 2025, Blown glass, 1 kg rice bag and cardboard. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[+]

Godelive Kasangati Kabena

Mbwa: Now Mine, 2025, Blown glass, 1 kg rice bag and cardboard. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

[-]

Lafleur & Bogaert

Godelive Kasangati Kabena

Mbwa: Now Mine, 2025. Blown glass, velvet pillow, duvet. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

Nilla Banguna

Wankito (umwanakaji). La femme forte, 2023. Printed fabrics designed and produced by Nilla Banguna, in collaboration with Patricia Banguna Kazadi, Josephine Kyungu Muloba, and Fernande Musha Sebelwa. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

Mickael-Sltan Mbanza

Nsala, 2025. Black and white video, 10 min. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

Pendezâ Mulamba

Mon chant, 2024. HD video, colour, sound, 6 min. 5 sec. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

Sixte Kakinda

Monologue, 2019-2025. Drawing. Courtesy of the artist. Graphisme and design: Maëlle Brientini. © Tadzio.

Lafleur & Bogaert

Lafleur & Bogaert, J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Collage, lettres composées à la main sur des sacs de courses cousus avec du fil de cuivre. Courtesy de l’artiste. © Tadzio.

Nilla Banguna

Wankito (umwanakaji). La femme forte, 2023. Printed fabrics designed and produced by Nilla Banguna, in collaboration with Patricia Banguna Kazadi, Josephine Kyungu Muloba, and Fernande Musha Sebelwa. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

Lafleur & Bogaert

J’aime RD Congo, 2024. Shopping bag woven from polypropylene “taux du jour.” Courtesy of the artists. © Lafleur & Bogaert.

Godelive Kasangati Kabena

Mbwa: Now Mine, 2025, Blown glass, 1 kg rice bag and cardboard. Courtesy of the artist. © Tadzio.

The exhibition Toxic Lands, Living Narratives builds on the research initiated during recent editions of the Lubumbashi Biennale, organized by the Picha Association [1] in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Conceived in collaboration with artist Sammy Baloji, it brings together artists whose works question colonial legacies and their lasting impacts on bodies, territories, and imaginaries.

The exhibition takes as its starting point the library and archives of Congolese philosopher Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, recently returned to the University of Lubumbashi. In his writings, Mudimbe analyzes how Africa was “invented” through the lenses of domination. However, he calls for a process of reclamation: rereading, shifting, rewriting, and subverting imposed forms to invent alternative ways of thinking. To reclaim is to reactivate the archive, open up new possibilities, and oppose dominant history with a plurality of living and insurgent narratives. In this spirit, the artists gathered here draw on colonial archives, mining memory, and performative gestures to compose new narratives.

The notion of toxicity runs through the exhibition, understood both as material pollution and as a social poison inherited from colonialism. Displaced and circulating, toxicity becomes a lens through which to read the destructive yet potentially transformative effects of extractive logics on cities in the Global South, particularly in Katanga, the heart of Congo’s colonial history. The exhibition examines multiple forms of contamination, as well as the possibilities for reconfiguration they open in a postcolonial context.

Moving between memory and creation, the exhibition becomes a space for confrontation as much as projection. It invites a rethinking of history, a reopening of archives, and a reconnection with narratives to imagine new possible trajectories.

[1] Picha, founded in 2008 in Lubumbashi by a collective of artists and cultural workers, takes its name from the Swahili word for “image.” The organization uses art and image-making as tools for storytelling and dialogue. Its vision: to build a sustainable ecosystem for art and culture in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by supporting local talent and fostering international exchange.

Exhibition journal