The exhibition refers to the relation between physical absence and mental space that the artists Mohssin Harraki and Joseph Kosuth explore in a challenging dialogue. Especially conceived for this exhibition by the artists, the space of the gallery is horizontally divided in two: the higher part of the wall in white is dedicated to Mohssin Harraki, the lower part in grey to Joseph Kosuth. Each artist develops his own subject matter: Mohssin Harraki evokes the question of the genealogy and Joseph Kosuth the etymology.

Mohssin Harraki always exits to the interior. His works bear the scratches of both departure for the non-native, and return. In each of his two cities, he has a postponed project: a project for Asilah when he is in France, and another for Paris when he returns to Morocco. And because he can be present in body in only one of the two cities, he typically struggles with his being there: estranged or affiliate.

Absent and present. Physically and emotionally. And in each city twice.

The timing and place of absence push him to “be” in the place he is in. To neglect one geography and embrace another, to be beyond a geographic domain, is naught but the very essence of migration, whether elected or forced: a dual migration, a dual expatriation. His book of history dissolves in the water of the Artificial Aquarium (2011). Here, history is turned into elements floating in the tank’s water and the book’s words are erased, leaving behind only its emptied body interacting with its environment.

The estrangement of immigrants is intensified when their means of living are complicated in the countries they move to: their families rush to treat them as though they’re from the new places, while the residents of those places refuse to embrace the immigrants in their new homes, ever demanding that they remain attached to/return to the places from which they came. When Harraki arrived in France, he lived in a caravan in Toulon onto which he affixed words such as “Meat from Morocco”, “Halal”, “Weight 82 kilograms”, “40% discount”, “Store in refrigerator”, and “Open here”. He used racism, advertising, and stereotypes to record upon himself the difficult outcomes of a stranger’s experiments in settling down in a non-native home.

“Why is it that racism exists in the world now?” Harraki asks in Two Questions to Joseph Kosuth (2008), to which Kosuth answers: “You can have a feeling of having power, even if it’s an illusion, by someone you see who is under you, for reasons that could be anything. And I think these things have perversely a value for the individual inside of the different social stratifications.” Kosuth articulates an answer stretched between two poles: the sense of power and the lack of power. He speaks of a moment where a (probable) presence of a (worrying) absent dominates. He goes on only to conclude “but I don’t have the answer now.”

In Histoire 2 (2013), Harraki re-writes history’s definition on pages of a book of glass. When the book’s pages are opened, they form a circle/flower, in which, from one page to the next, the words gradually flow down from the never-ending. The artist’s lines resemble those with which he traced before in Problem no. 5 (2011), creating equations in the form of family trees, of those who have ruled Arab countries in the name of politics or wealth or religion. The placement of a name in the family tree is prioritized by the power of the person holding that name, where his story/words might as well be a source for advisability. In Thrones 0 (2013) he inscribes four family trees of four Arabic countries: Bahrain, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Jordan on pieces of white cloth.

What does Harraki use in his works other than his body, his history, his language, his experience, his estrangement, and his trips home? Harraki makes use of books in philosophy, French and Moroccan. He re-writes on the effect of contrived events on real events, how they reach their audience distorted, in turn contributing to the audience’s creation of the event. How a reading of full reality is completed to become our contrived history. He is concerned with the never-ending relationship between the presence of the absent and the absence of presence. He asks: does the manifestation of something in particular contribute in one way or another to its disappearance? He answers: “when (things in) the picture manifests, the things (in it) vanish, and absence becomes present”.

— Ala Younis

As one of the main actors and definers of Conceptual Art since the mid 1960s, Joseph Kosuth works within the field of art to make meaning. His matter is the cosa mentale and how to convey his investigations to the audience utilising words, texts, images, ideas. Manifestations range from glass, photography, printing, neon installations, wallpaper, to real objects, exhibition curating or language. Representation, appropriation, quotation, site specific architectural interventions, writing and teaching are amongst the devices he works with. He ceaselessly questions the context, cultural history and contemporaneity through public art, sculptures and statements that challenge any anti-intellectual status quo and seek to involve the viewer/reader’s body and mind.

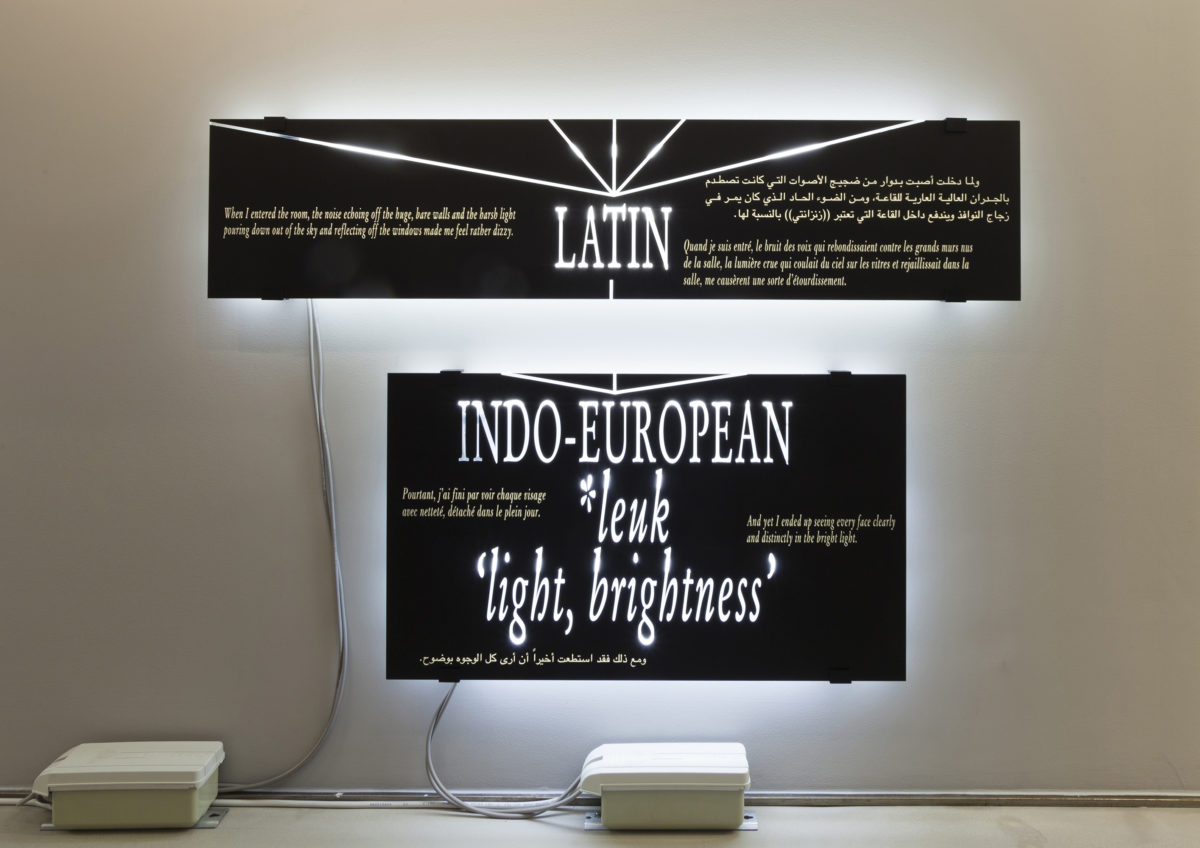

From 1965, Kosuth studied art in New York, punctuated by major dialogues with the likes of Ad Reinhardt, and, on one occasion, support from Marcel Duchamp just before he died, which led him to develop his critical stance on modernism, formalism and the traditional gravitas given to painting and sculpture. He also researched and practiced other disciplines such as anthropology and philosophy. His famous proposition is that of “Art as Idea as Idea” – a concept still central in the exhibition “absence-presence, twice”. The question of visibility and artistic production is repeated carrying countless layers of significance. Kosuth’s art is fundamentally concerned with relations between relations, proximity, gaps and self-reflexivity. One of his ongoing projects which began in Oslo in 1995 is entitled “Guests and Foreigners” based initially on Hans-Dieter Bahr’s work on the subject. “There”, Kosuth has written, “is the experience of the artist as ‘guest’, and the artist as ‘foreigner’, working with a language he/she does not speak nor read, yet ‘speaking’ with that language within another system (art) which has a cultural life within an international discourse. That discourse is a context without a border, a context to which anyone can be, at any moment or location, either a foreigner or a guest – the artist no more or less so than the viewer/reader.”1

Kosuth traveled to Europe and North Africa in 1964. That is when he made his first eventful trip to Morocco and dined next to Simone de Beauvoir at a dinner with Jean-Paul Sartre in Montparnasse. His recent projects in Paris include no less than an exhibition on the original exterior walls of the now indoor 12th castle of the Louvre (neither appearance nor illusion, 2009), as well as a permanent neon textual intervention citing Michel Foucault on the four open book towers of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France to be completed in 2014. This followed his project in Figeac honouring Champollion, which has been acclaimed as the most successful public commission in France.

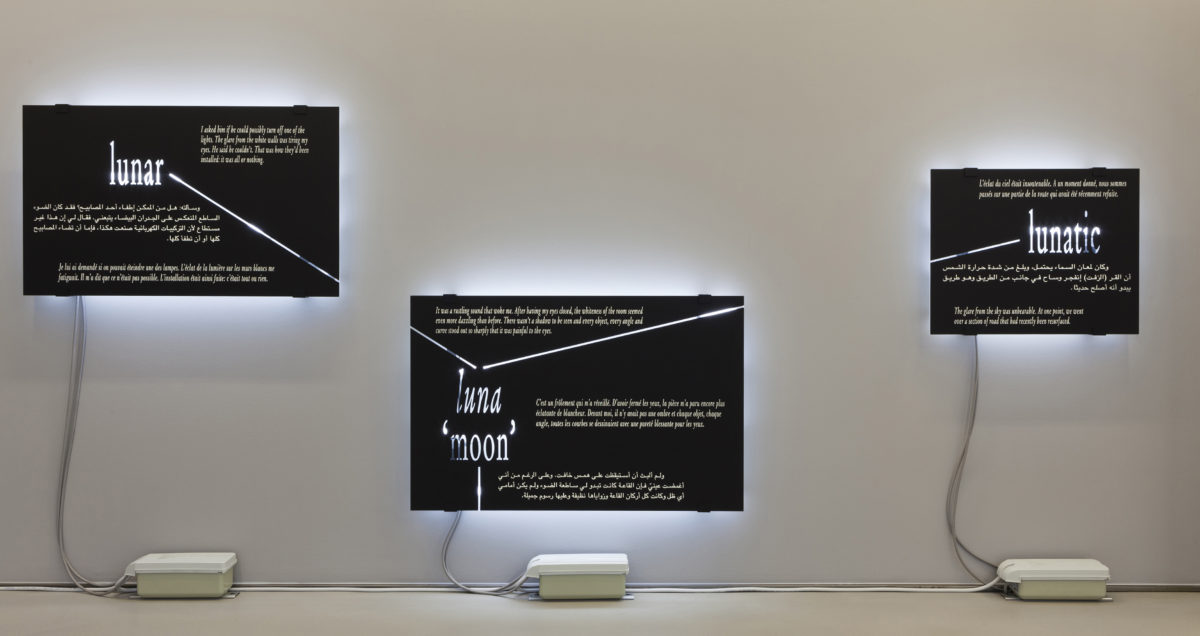

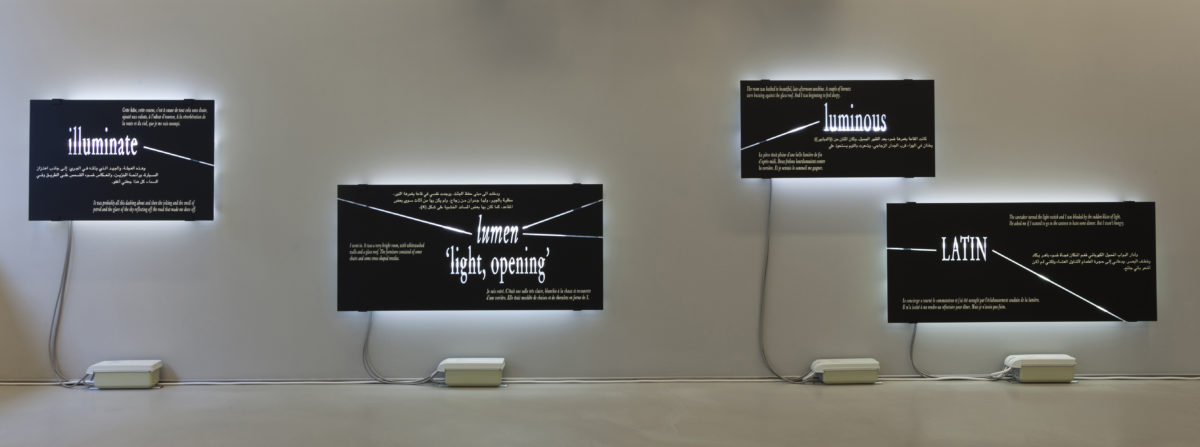

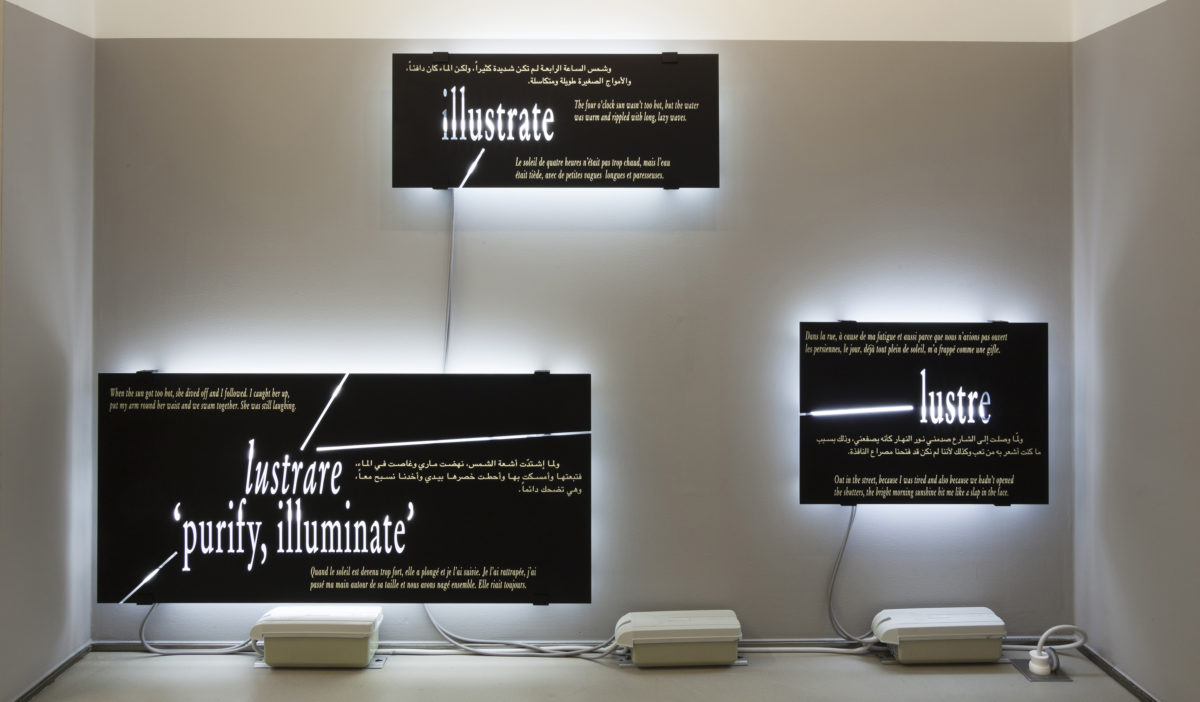

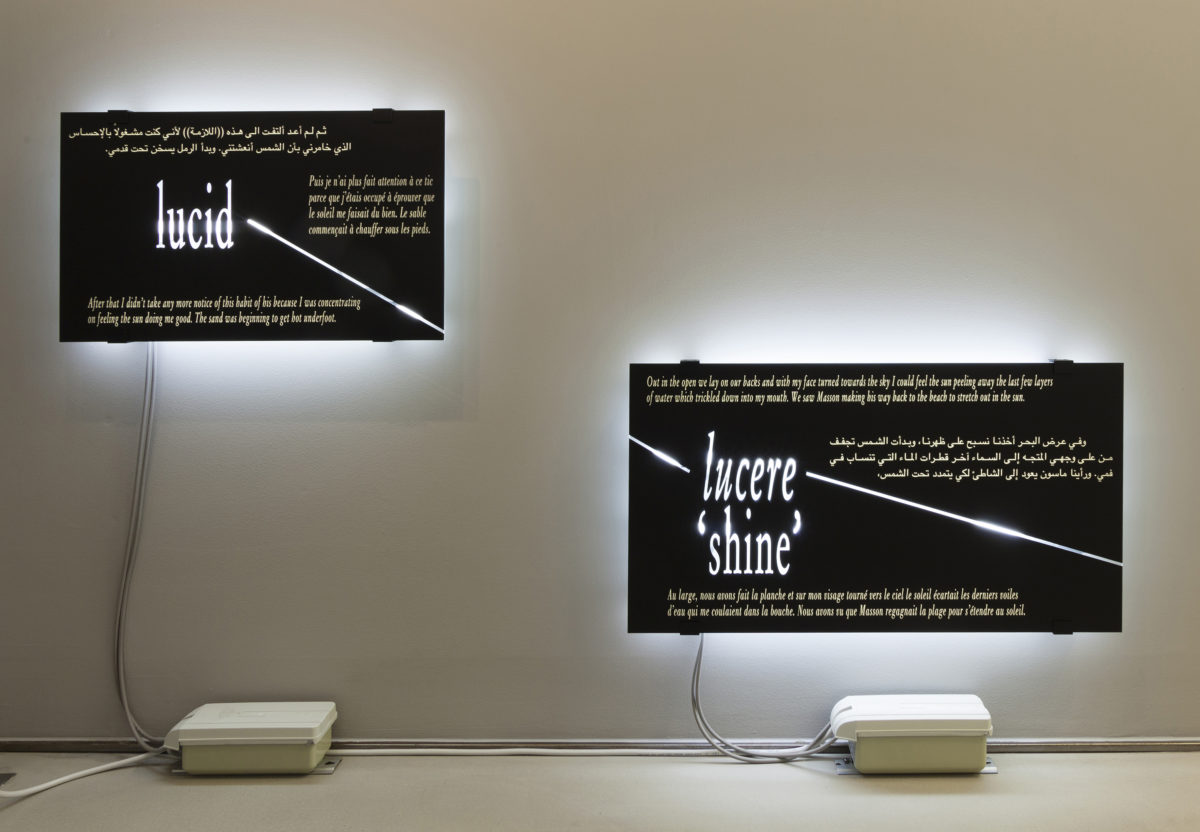

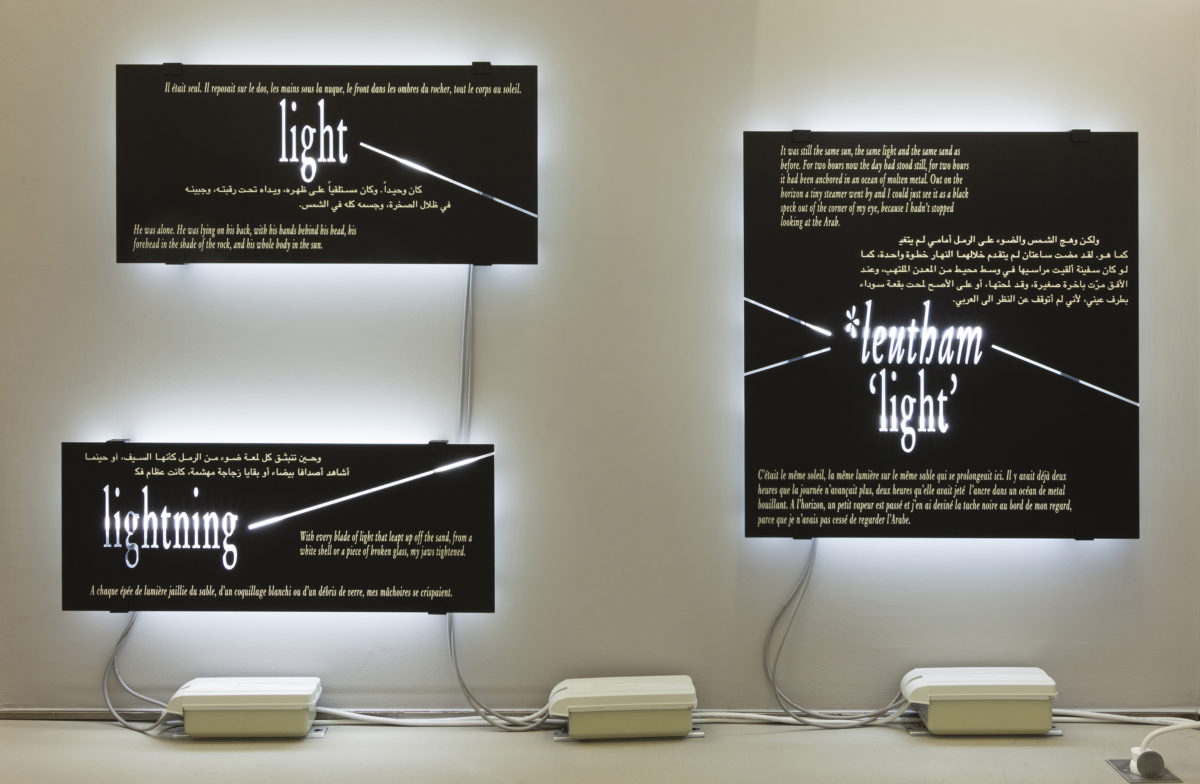

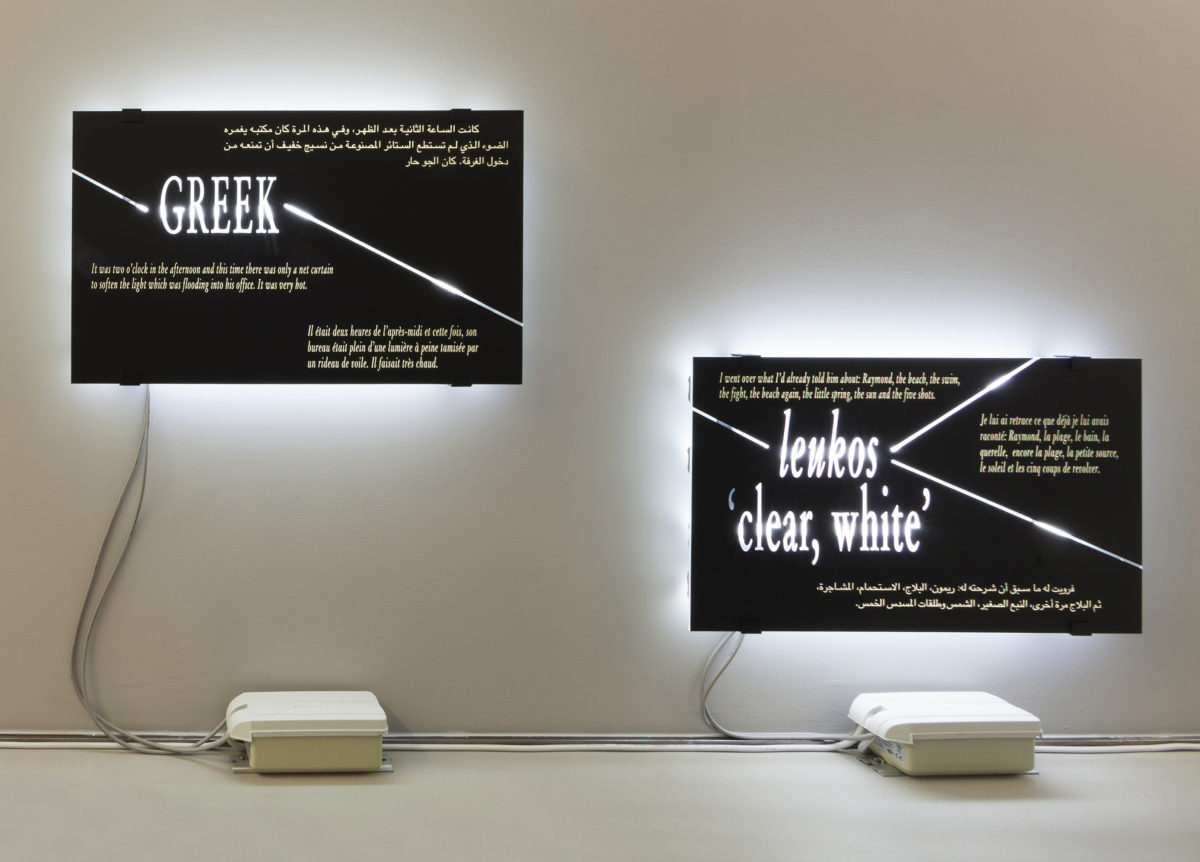

On the occasion of this two-person dialogue with Mohssin Harraki, Kosuth utilizes the English etymology of the word ‘light’ as a connective structure for an installation comprised of individual works, putting in play fragments from Albert Camus’ 1942 book L’Étranger (variously translated The Stranger or The Outsider in English) in French, Arabic, and English.

In 2008, Harraki had asked Kosuth to answer two questions about racism in his Video-Dialogues. Part of the response was as follows: “Like the steering of a boat, one needs to be able to move society in a better direction.” The context of their relation, their different, shifting and debatable positions as guests and foreigners, and Kosuth’s socio-political observations of certain currents are at play in the construction of this new work.

— Caroline Hancock

With thanks to Cécile Bourne and Seamus Farrell

1. Joseph Kosuth, “Guests and Foreigners: Corporal Histories”: an installation for the American Foundation for Aids Research, Berlin: Berlin Press / New York: American. Foundation for AIDS Research, 2001, p. 9.