“I am a creature of the mud, not the sky. I am a biologist who has always found edification in the amazing abilities of slime to hold things in touch and to lubricate passages for living beings and their parts”.

Donna Haraway, When Species Meet, 2008

Between debris and “things”

Earlier this year, the Archaeological Unit of Saint Denis offered me a 300kg stock of animal bones dating back to the 10th and 12th century AD. These bone remains are those of domesticated herd animals and pets, or of wild animals that were hunted and killed for food.

Having completed all the archaeological and scientific assessments and collected all informative data, the remains were only taking up space in the centre’s storage. And so, as a last resort, the archaeological unit decided to reach out to artists before destroying the stock.

Before I received them, these bones had undergone numerous biological and categorical transformations, each time demoted into new classifications. From vital living tissues to animal carcasses rotting in riverbeds, and then, picked clean of all flesh after centuries of decomposition and biodegradation, they found new life as “objects” of scientific interest. Finally, after they had been exhausted by study, the bones were degraded into useless debris. Jane Bennett describes demoted objects according to their change of status from more esteemed to less, from higher rank to lower. “Demotion”, she says, “emphasizes the power of humans to turn nonhuman things into useful, ranked objects.” In other words, the object is ranked according to human judgment, and the demoted object is a body judged defective in relation to normative standards and values. As long as the object retains the aura of a certain value, it remains, for the most part, an object worthy of possession. But what happens when the demotion goes all the way, when the object falls so low, so below the standard as to become irredeemable?

The denatured “object,” after it is deprived of all its natural qualities, becomes a “thing.”

The fragility of things

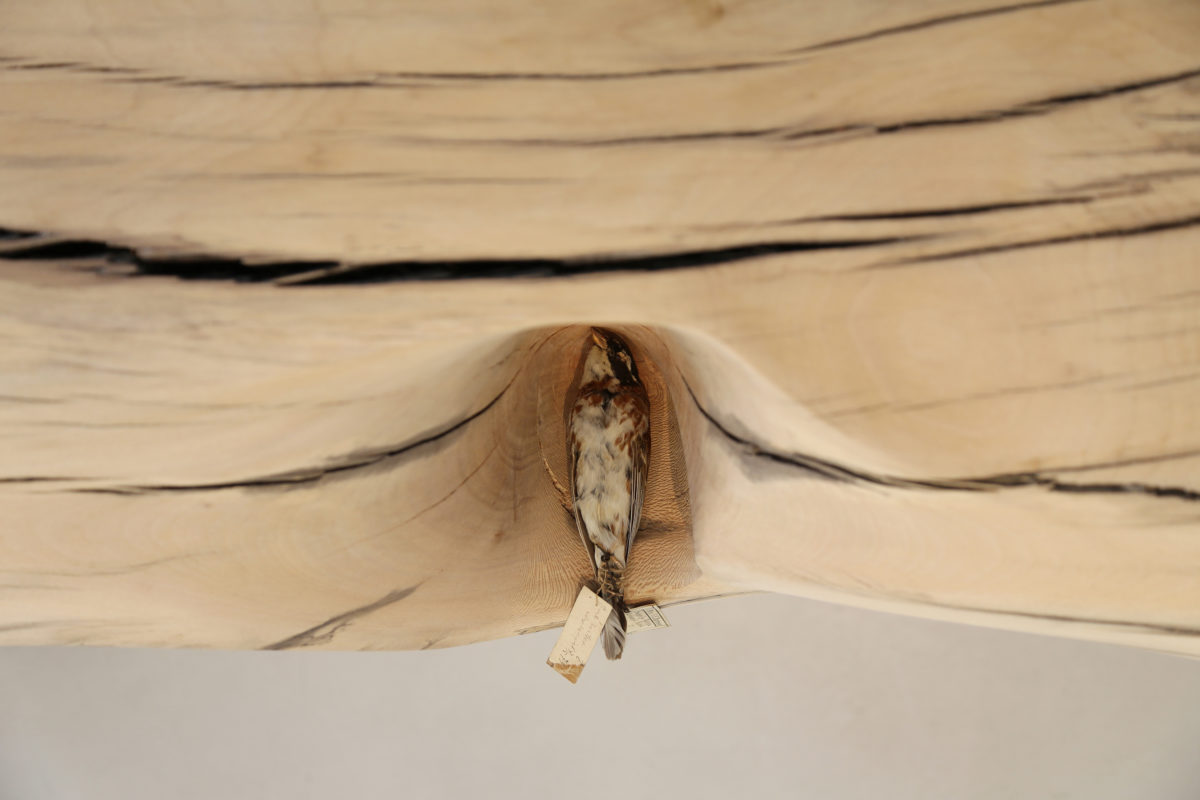

The installation Where do birds go to hide turns the encounter with objects freed from normative standards into a spectacle. A dead tree; animal bones; the skin of a taxidermy bird: each of these things on its own is mere debris. But when they are brought together, when they are grafted onto one another in such a way that creates relationships between them, they rise to a new status: that of an active encounter. They are given emotional value: these long-dead things become bodies with the capacity to affect and be affected.

In agricultural botany, a graft is a sprout inserted into a slit on a trunk or stem of a living plant, from which it receives sap. In medicine, it’s a piece of living tissue that is transplanted surgically to replace diseased or injured tissue. In the former, grafting is often used to create new varieties of a single plant, or an entire new species of plant. In the latter, grafts can sometimes be made between members of different species, that is, human and animal. In both cases, a new appearance, a new life is granted: when the sap, or blood, begins to circulate seamlessly through the organism, the graft has been successful. By performing the assemblage of fragile things, connective agency is first enabled and then allowed to flow. This is not a metaphorical association of signifiers; a useless corpse has no autonomous desire to be anything other than what it is. These encounters instead give us a glimpse into the power of matter.

Likewise, sometimes, a tree can morph and change its shape in order to host the fall of a dead sparrow (or is it only sleeping?).

Gestures of reparation, gestures of care

For some time now, I have been looking at the archaeological site as a space where artefacts and structures from other times and places break out into the open. The unbroken, valued artefact is given a thick layer of cultural meanings; it can set record-breaking results on the auction market or become a museum fetish. As for the demoted ruined object, it requires attention and care. Each situation suggests a different possible form of addressing the irreducibility among the agents of these relations. The archaeological questions are not only aimed at the object itself but also at the relationship between the object and the area in which it was found and the other objects associated with it. The term “archaeological objects” encompasses both “artefacts” (manmade objects) and “ecofacts” (fauna, plants, etc.). By looking at the life cycles of objects and the complexity of preservation and representation of matter, the relationships and tensions between the organic and synthetic, figurative and the abstract, the found and made object are revealed.

To think beyond the life-matter binary, to acknowledge that as humans we are not autonomous but part of “vital materialities” is to allow moments of enchantment to happen: to be enchanted is to be transfixed, spellbound, speechless and subject to immobility.

— Ali Cherri, 2017