Ben Rivers, The Minautaur, 2024. 16mm film, sound, 13 min. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery.

[+]Ben Rivers, The Minautaur, 2024. 16mm film, sound, 13 min. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery.

[-]Francisco Rodríguez Teare, El oro y el pez (The gold and the fish), 2026. Full HD video, 16/9, sound, 21 min. 09 sec. Courtesy of the artist.

[+]Francisco Rodríguez Teare, El oro y el pez (The gold and the fish), 2026. Full HD video, 16/9, sound, 21 min. 09 sec. Courtesy of the artist.

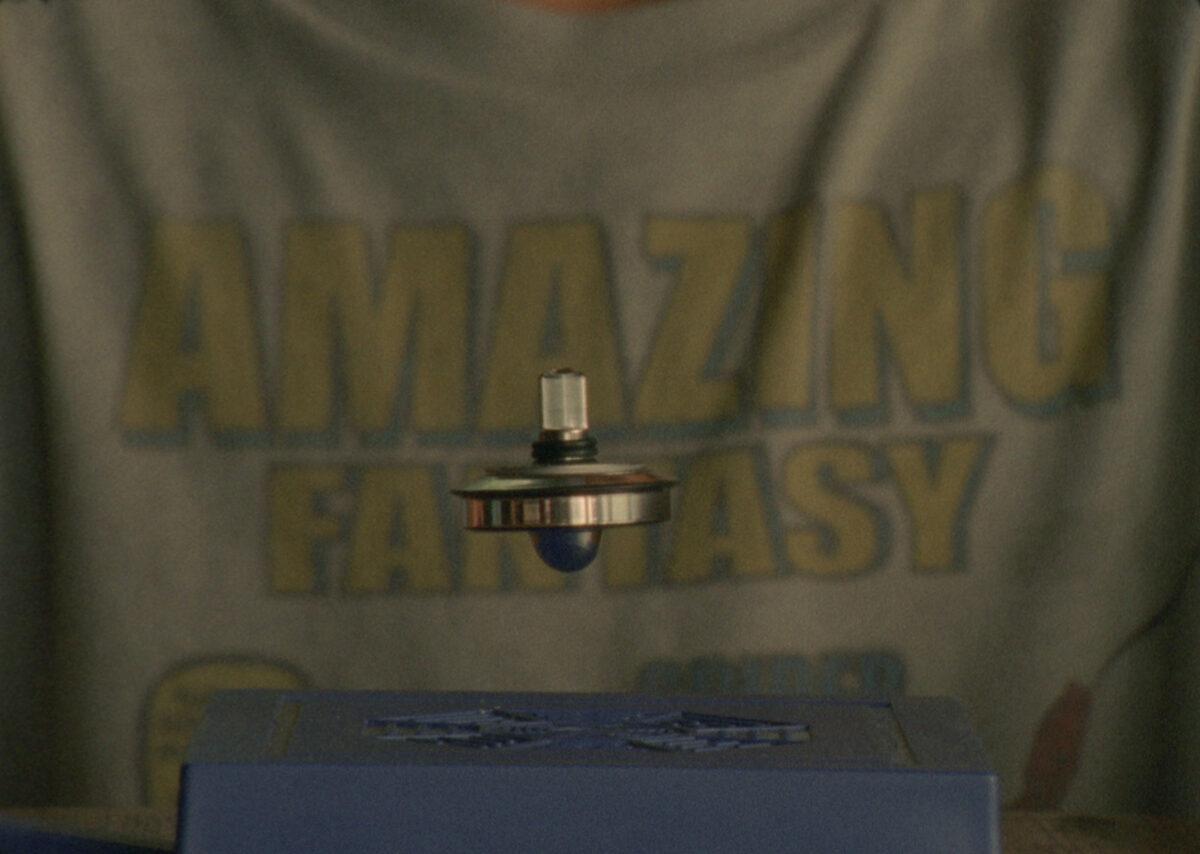

[-]Ana Vaz, Amazing Fantasy, 2018. 16mm film transferred to HD, sound, 2 min. 36 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Spectre Productions.

[+]Ana Vaz, Amazing Fantasy, 2018. 16mm film transferred to HD, sound, 2 min. 36 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Spectre Productions.

[-]Ben Rivers, The Minautaur, 2024. 16mm film, sound, 13 min. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery.

[+]Ben Rivers, The Minautaur, 2024. 16mm film, sound, 13 min. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery.

[-]Ana Vaz, Amazing Fantasy, 2018. 16 mm transféré en HD, son, 2 min. 36 sec. Courtesy de l’artiste et de Spectre Productions.

[+]Ana Vaz, Amazing Fantasy, 2018. 16 mm transféré en HD, son, 2 min. 36 sec. Courtesy de l’artiste et de Spectre Productions.

[-]

Ben Rivers, The Minautaur, 2024. 16mm film, sound, 13 min. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery.

Francisco Rodríguez Teare, El oro y el pez (The gold and the fish), 2026. Full HD video, 16/9, sound, 21 min. 09 sec. Courtesy of the artist.

Ana Vaz, Amazing Fantasy, 2018. 16mm film transferred to HD, sound, 2 min. 36 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Spectre Productions.

Ben Rivers, The Minautaur, 2024. 16mm film, sound, 13 min. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery.

Ana Vaz, Amazing Fantasy, 2018. 16 mm transféré en HD, son, 2 min. 36 sec. Courtesy de l’artiste et de Spectre Productions.

On the occasion of the exhibition Amazing Fantasy, three films are being shown in the gallery. These films are not watching themselves, they talk with each other. As you observe the children who guide them, you may see yourself. Through the grace of a mental journey, past will become present again, and you will see things with fresh eyes. Order does not matter here. The editing will be done at the end, after the visit.

Freed from themselves and from the hefty cinema machine, these films have the power of a poem’s apparition. They come from afar and create a form of vertigo as they rise to the surface of time. Take them with you: they will be the viaticum of your imagination as the familiar memory of unknown lives will rise aboard the lift of sensation.

Tangle of myth, what would you become without the thread unwound by the children in Ben Rivers’ film? What if the Minotaur was a clumsy boy ostracised by his mates? The game is so serious that it is hard to doubt it. With its flamboyant cinematography, The Minotaur combines the savage gravity of childhood with the mineral aridity of a Mediterranean island. Ben Rivers, sculptor by training, has been directing films for over twenty years. He is one of major filmmakers who have broken down barriers between cinema and visual arts, without necessarily binding himself to the experimental cinema family, in the historical sense. Although the medium itself and the use of film are characteristic of his filmmaking, what his work tells and depicts is somehow very personal, drawing equally on tales (fantasy or horror), documentaries, science fiction, poetry, diaries and essays. If one had to find a word to describe his work, the most accurate would be ‘essay’: the essay as a means of inventing new narratives for a world damaged by speed and excess. The places explored by this cinema wizard are parallel spaces, on the fringes of society, metaphorical or real islands. The Minotaur is part of a feature film, The Mare’s Nest, which was screened at the 2025 Locarno International Film Festival. With its ecological dimension, it rightly won the Pardo Verde award. Inspired by Don DeLillo’s play, The Word for Snow, The Mare’s Nest is a futuristic fable whose protagonists are children. Filmed on the island of Majorca, the section entitled The Minotaur, screened in the gallery’s basement, revives the ancient myth by questioning the attribution of violence which generally weighs heavily on the Minotaur’s shoulders. But nothing is so certain.

In El oro y el pez (Gold and Fish) by Francisco Rodríguez Teare, filmed in the Bolivian Amazon, the gestures and games of the T’simane community’s children seem to recreate the atmosphere of places that once belonged entirely to their ancestors. This work is an unreleased piece by the Chilean artist and filmmaker, whose films have been shown and celebrated at numerous festivals and exhibition venues around the world. Although childhood is never a central theme there, it is prevalent due to his free approach of storytelling and because, when children appear, they do take control of the film. By refusing to choose between fiction and documentary, the filmmaker offers them this space and allows the different scenes in the film to not fit together perfectly (“continuity error is the true labyrinth of cinema”, said Raúl Ruiz). Although less narrative than his feature film Otro sol, El oro y el pez benefits from the quality of an artist’s gaze that plays with the narrative and thwarts it in order to avoid any control of the film over its own protagonists. We can see how essential this political dimension is in this film, following the children of the T’simane Amerindian community of Manguito, in the Bolivian Amazon. Around artificial ponds created for fish farming, the children, after feeding the fish, return to their games and activities. It is almost ordinary, but the language they speak is fascinating. Having resisted disappearance, it is revived by the young people who make it resonate. There is no exoticism here, which adds something striking and obvious to the film.

Finally, directed by the Brazilian artist and filmmaker Ana Vaz, the film Amazing Fantasy gives its title to this exhibition, for which it was the initial inspiration: to present short works that can be grasped as a whole before approaching them little by little, moving away from them, returning to them and retaining an almost complete memory of them, like a poem whose page would be inscribed in our brains. A wonderful antidote to the senseless flow of images, a contemplation rather than some hypnosis. Presented at the entrance of the gallery, this haiku marks the beginning and the end of the visit: it welcomes us and we bid it farewell as we leave. We are under its protection. In this film made in Japan, we see a child observing a levitating object spinning around. And us, where do we stand while we watch it? There and elsewhere, undoubtedly. Amazing Fantasy is a distillation of Ana Vaz’s relationship with cinema: art of the visible and the invisible, a medium capable of transporting us through thoughts and senses, an instrument for expanding our fields of perception beyond our human condition. This film, of course, cannot do justice to the complexity of Ana Vaz’s cinema, particularly given that it also serves as a poetic and critical tool for her to reveal injustices swept under the carpet of colonial capitalism — her short film Apiyemiyekî? and the feature film It Is Night in America (presented at the Locarno Festival in 2023) echo this violence in particular. However, this tiny part of an ongoing filmography, recently incorporated into a film about radioactivity, this opuscule, through its title and magically, takes us back to the Greek fantasia, both representation and apparition. A marvellous apparition.